Honoring Razia Bhatti: The fearless editor who challenged Pakistan's power elite

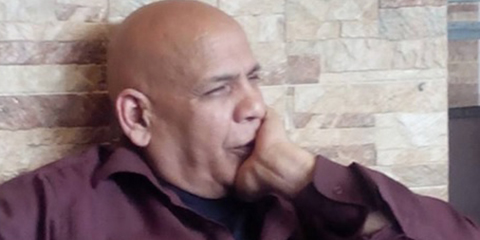

JournalismPakistan.com | Published: 15 August 2025 | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

Razia Bhatti was a pioneering editor who founded Newsline, a magazine known for its fearless journalism. Her commitment to truth and integrity left an indelible mark on Pakistani media.Summary

ISLAMABAD—There is a strange and aching discord when death comes too soon for a life of fine pedigree, a life forged in craft, tempered in courage, and shaped with the patient hand that lays each stone of a legacy. We grow up in the soft deceit of expectation, perhaps taught by old stories or by the quiet reckoning of human hope, that such lives will be granted their long evening; that those who have withstood many tempests will be spared a few still waters before nightfall.

But when the ending comes before its rightful time, it does more than cut the thread; it unravels the cloth. The absence is greater than the measure of the person, because they were more than flesh and name; they were an idea, a cause, a promise breathed into the air and kept alive by their living. In Karachi, where the air carries the salt of the sea, the smoke of unrest, and the weight of unfinished valuations, Razia Bhatti died on in March 1996, quietly at home, aged fifty-two. She had spent all her working days walking into the wind.

Founding Editor of Newsline Magazine

As founding editor of Newsline, a political monthly whose lean pages held more truth than many dared to speak in private, she stood for democracy, for the fragile yet stubborn hope of change, and for the unfashionable right to print what the powerful would rather see burned. Her death came while the city still simmered in its own turbulence, only seven months after she had faced policemen at her own threshold. They had come at the bidding of a provincial governor, angered by an article she had published. The summons to the police station was meant to bow her head; the charges, brittle as old paper, were meant to bind her hands. She refused. The charges fell away, as such things often do when they meet a stillness that does not give ground.

International Recognition for Courage in Journalism

Those who knew her did not call it bravery; they called it simply Razia. She had stood through enough such sieges for the International Women's Media Foundation to fly her to Washington a year earlier and place in her hands their Courage in Journalism award. She carried it not as a trophy, but as a reminder that the cause was not hers alone. There was an irony, the sort history sets down without comment that Newsline itself had been born from the weight of censorship. In 1989, she left The Herald, unwilling to blunt its edge against policies she found indefensible and corruption she knew to be corrosive. Several women from that newsroom followed her, and together they built Newsline: independent, staff-owned, a small ship in deep water, kept afloat by the stubborn faith of its crew.

Standing Against Censorship in Pakistan

In a country where the printed word can summon undertones in the dark or violence in the street, she persisted, not with the noise of a firebrand, but with the steady hand of one who believes that truth, however unwelcome, is entitled to its day in the light. And then, in a moment, she was gone. Not the victim of the fist or the gun, but of a sudden, a brain haemorrhage, he last concession of a heart that had worked too long under unrelenting pressure. Young death deprives not only the future; it rearranges the past. The line of a life becomes not a road, but a series of bright, sharp moments, their light fiercer for being final. The arguments, the newsroom hours, the stubborn stands at the door, all are recast in the knowledge they will not come again.

Those left behind find time altered; the days that follow seem both longer and emptier, measured against what might have been had the days been kinder. And yet, there is one quiet mercy: in leaving early, she spared the world the sight of her diminished. In memory, she remains at full height, standing in her doorway, unyielding. Perhaps that is why early death unsettles us so. It reminds us that no courage, no craft, no greatness of spirit can bargain with the body's private clock. It is a theft that leaves not only grief but the echo of an unanswered question: how much more might have been written, spoken, changed — if there had been more time?

Personal Loss and Family Legacy

She left behind her husband, Gul Hameed Bhatti, himself a mentor to most of us, a perfect gentleman of the old order; he never came to terms with Razia's death. I can still see the scene: the small office of The News International in Karachi, the warm, diffused light on a desk scattered with papers, and he, seated behind it, diminished not in stature but in spirit. I sat across from him, coaxing him, almost pleading, to take his anti-hypertensive tablets. Once a commercial flyer who had found his second calling in journalism, Bhatti seemed, in those days, a man unmoored. The sudden loss of his most loving wife had taken from him not only the comfort of companionship but the will to live in the world she had left behind. He carried on, yes, but with the air of a man walking home through empty streets after the lights have gone out.

She also left behind her children, Kamil and Sara; a sister, Fareeda Boudrey; and three brothers, Karim, Rahim, and Rafeeq, all of Karachi. Her absence left the city's clamour a shade quieter, the profession poorer, the fragile architecture of fearless journalism with one less stone in its arch. But her words remain on the printed page, print already older than her death, and they will keep speaking, stubborn as the surges of the city she called home. Some lives seem to stand like pharoses on a coastline, resisting each storm, their light unshaken, until the day the light is suddenly gone, leaving the sea and the night unaltered but somehow colder. Razia Bhatti's life was such a life.

The End of a Golden Phase in Pakistani Journalism

In 1996, when the Pakistan Press Foundation called her passing 'the end of a golden phase of journalism in Pakistan,' it was not hyperbole but the simple measurement of loss. She was fifty-two, her career not a straight road but a long resistance, almost thirty years of leaning into the wind, and never stepping back. For those who sought to tame the Pakistani press, she was a formidable adversary. The threats were many, the harassment frequent, yet she kept writing, on the rights of women, on the corruption that coiled through politics, on the fractures in the nation's moral essence.

Early Career and Rise to Prominence

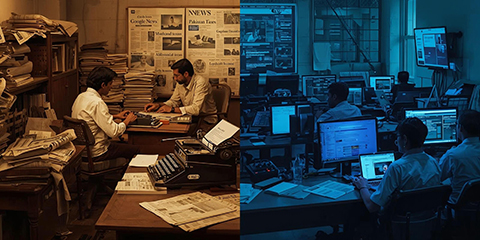

Her journey began in 1967, stepping from Karachi University, where she had taken her Master's in English and Journalism, into the newsroom of The Illustrated Weekly of Pakistan. In time, it became The Herald, shifting from a lifestyle magazine to a political monthly, and in 1976, she was its editor.

Then came the coup of General Zia-ul-Haq, and with it, the years of enforced silence, when dissent was choked with the language of piety and the blunt instruments of censorship. Razia's expression did not soften. Once, Zia himself, in a press conference, waved a copy of her work and announced he would not tolerate such journalism. She took it as proof she had struck the right nerve.

Defying Military Dictatorship

The Pakistan she lived in had known, under both uniforms and civis, rulers who measured success in the commonness of their survival. Illiteracy persisted, poverty deepened, and the air thickened with corruption, bigotry, and the intimidation of those who spoke too plainly. To keep writing in such a climate was not just work; it was a daily act of defiance.

When told to trim her canvases to suit the government's wind, she resigned from The Herald rather than alter her course. Most of her newsroom followed her out, and together they launched Newsline. Its first issue, in July 1989, opened with her own words: And then forty-two years after having become an independent country, Pakistan seemed to have bartered away the promise of its birth. To a whole generation of Pakistanis, fear, violence, authoritarianism, and deceit represented the new normal, for they had known no other.

Newsline's Fearless Investigations

Working on the slimmest of budgets, Newsline took on drug trafficking, political graft, the exploitation of women, and the abuse of religion. It did not flinch. In December 1994, it was uncovered that Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto's failure to marginalize the killings and chaos that had turned Karachi into a city under siege. The government's answer was to ban the magazine from Pakistan International Airlines flights, a small, futile blow, answered only by further reporting.

They came for Razia again in 1995. Police raided her home in the early hours, at the order of the Sindh Governor, Kamal Azfar, over an article that displeased him. The protests from journalists and human rights activists were swift and loud enough to make him retreat, withdrawing the charges in their entirety.

A Philosophy of Fearless Journalism

In Newsline's first issue, she had written, 'The press in Pakistan shares the guilt of this nation's state. It has been silent when it should have spoken, dishonest when it should have been forthright, succumbed when it should have stood fast.' She had lived by the opposite creed, holding the line where she stood. The toll was invisible until it was final. A brain haemorrhage stilled her in 1996, not the result of the hand that threatened, nor the power that schemed, but the quiet, private surrender of the body after too many years lived under pressure. She was a rebel; she rebelled, even risking her life, not complying to prescriptions dispensed to control her hypertension. It wasn't any excuse, it was an attitude, she refused re-tailoring, because there was something she was fighting against, the system, the asks, and her internal callings.

Legacy of Journalistic Virtue

Her death was not simply the loss of a person but of a voice, one that had learned the difficult art of speaking without fear, in a place and time when fear was the common place. Razia possessed the three hard-won elements of journalistic virtue, courage, commitment, and credibility. They were not slogans she adhered to but qualities that shaped her work and her person. She built Newsline from its inception into a receptacle unlike any other in Pakistan's press, fiercely independent, unswerving in its investigations, and determined to set foot where others hesitated.

She tramped on the power of the intelligence services; she walked into the long shadow of the military in the post-Zia years; she named the narco-barons, called out the corrupt, and shone light on the persecution of minorities and the diminishment of education. Where others measured the danger and stepped back, she measured it and stepped forward. Her editorship was not only a position; it was a guardianship. She understood the double-edged gift of press freedom, the right to speak matched by the responsibility to be exact. A story without foundation, to her, was a house built on sand. She would question a contributor until the source stood visible in her mind's eye, or the piece would not run. Even the phrase 'informed source' drew her objection; it was too thin a fabric to clothe a truth. Words, she believed, had consequences that could outlive their writers, for good or for harm.

Leadership Style and Editorial Vision

Her style as a leader was not to dictate but to convene. Late at night, with her team around her, she would weigh the pulse of the nation against the slow heartbeat of a monthly magazine, asking not only what was news, but what was worth the cover. She understood that a monthly was not to chase the day's noise, but to hear what lay beneath it, to draw lessons that outlasted the week's tempests. The spirit that drove her was not simply that of a journalist, but of a reformer, unwilling to leave unchallenged the injustice, abuse, or small cruelties that passed for normality. That spirit earned Newsline its reputation as an unsparing critic of oppression, and earned her the attention, and the threats, of those who would prefer silence.

Quiet Courage in the Face of Threats

Her courage was quiet. She met threats, from state agents or street-corner evangelists, with the same calm refusal to be moved. Friends urged her to take precautions; she would smile them away, as if to say that her convictions were her only shield worth carrying.

Yet, beneath the professional steel, she was a woman of gentleness. She disliked the staged glitter of Pakistan's power circles, avoided the ceremonial tables where the rich and influential congratulated one another. She kept herself for her work, her friends, and her family. Razia Bhatti was, in the end, a voice of clarity in a country often drowned in noise. Her like does not pass this way often, and when it does, it leaves behind a standard to measure by, and a silence to honor.

KEY POINTS:

- Razia Bhatti founded Newsline magazine in 1989.

- She fought against censorship and defended press freedom in Pakistan.

- Bhatti received the Courage in Journalism award from the International Women's Media Foundation.

- Her sudden death in 1996 was a significant loss for journalism in Pakistan.

- Bhatti's legacy continues to inspire journalists today.