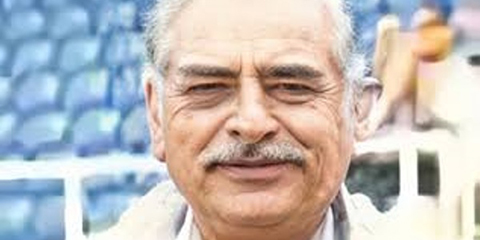

The voice that made sport sacred: Remembering Farooq Mazhar, Pakistan's legendary sports commentator

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 4 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

ISLAMABAD—There are names in journalism that do not just echo through the stadiums of time—they resonate like chants from the soul of a people. Farooq Mazhar is one such name. A sports journalist par excellence, he did not write about the game; he entered it. With each word, he stepped onto the pitch, onto the ring, into the crease—not only as a spectator but as a raconteur of destiny, as if the game itself needed him to exist in memory.

To speak of Farooq Mazhar is to speak of a man who understood that sport is not just competition, but a cathedral of human emotion. In the arc of a batsman's follow-through, in the last breath before a penalty corner, the knockout, in the agony of the near-miss—he saw metaphors for the larger dilemmas of existence. Time, loss, redemption, hope, all played out in the physical theatre of sport, and he captured it not as reportage, but as poetry-in-motion. His prose shimmered with pathos, not because he embellished, but because he witnessed—and more importantly, because he felt.

The Cartographer of Spirit

In a world obsessed with stats, Farooq Mazhar remained a cartographer of spirit. He was less interested in the scoreboard and more in the soul-board—what this loss meant to the child in a village glued to a transistor radio, or what that victory meant to a father who named his son Imran after a captain who once lifted a nation. He knew that behind every athlete is not just sweat, but a universe of silent prayers, of aching mothers, of forgotten coaches and silent sacrifices. And he brought these truths to the fore—not loudly, but with the depth of reverence.

There is a peculiar grace in witnessing greatness and knowing how to tell its story. Many see, fewer observe, but the rarest—like Farooq—understand. His was not the detachment of the objective journalist, but the intimacy of a seer. Where others just described the outcome, Farooq narrated the becoming. He made you feel what it was to lose by an inch or win by a breath. His vocabulary of sport was carved not from statistics but from silence—the silence before the whistle, the silence after a last run, the silence of a nation holding its collective breath.

Unwavering Commitment to Truth

But perhaps the most profound aspect of Farooq Mazhar's legacy is his unwavering commitment to truth. Not the rigid truth of numbers, but the fluid, often painful truth of humanity. He was not seduced by celebrity nor cowed by power. If a hero fell, he reported it not with malice but with mourning. If an underdog rose, he celebrated it not with hyperbole but with humility. His writings knew the difference between noise and nuance.

In him, journalism was not an act of profession—it was an act of philosophy. He believed that to cover sport was to chronicle civilization in miniature: conflict without war, excellence without cruelty, loss without meaninglessness. He recognized that in every sporting arena, we rehearse our hopes and fears as a species, again and again, in the dream that maybe this time we'll get it right.

A Custodian of the Sacred

Now, with his name printed into the annals of memory, Farooq Mazhar stands not just as a sports journalist but as a custodian of the sacred. In every crumbling newsprint article, in every long-lost radio commentary, in every archived interview, his voice still echoes—not merely about who won or lost, but about who we are and what we long to become.

First Encounters and Lasting Impressions

I have never been shy in professing my respect, affection, and admiration for Farooq Mazhar. Our first meeting, in the hushed corridors of The News International, was entirely unplanned. He was the Resident Editor there. I stepped out of his office, thinking I had just encountered a man wrapped in arrogance. I had long been a quiet admirer of his voice—particularly in hockey—the low pitch, the quiet authority, the way it pressed meaning into every syllable. His write-ups evinced the same composure, the same weight. And yet, at that point, I did not know the full breadth of the man: his literary reach, his journalistic stature. I knew of his renown in the media worlds of hockey and cricket, but not of the vastness of his mind.

It did not take long for that first impression to dissolve. Behind the impact of his exterior—yes, he was an alpha in the truest sense—there was a heart that could be melted. Soon, he had not only earned my regard; he had won my gratitude. Firm, resilient, undaunted, always upfront—he was a mentor in the rarest sense: one with whom you could sit for hours and lose yourself in the labyrinths of philosophy and abstraction. He was an intellectual in the purest, most instinctive way. I was startled when he told me he had not completed his Master's degree, that he was barely a graduate. And yet, he had taught himself—absorbing literature, history, politics, and sport until they were part of his soul.

The Literary Mind and Personal Quirks

Farooq was a liberal in both temperament and mind, but he carried his peculiarities—chief among them a deep affection for Winston Churchill. He adored Churchill's works, and soon after discovering my curiosity, he presented me with two of his books. I fell for their style, their depth, the craft of evocative prose. It was in the West Indies—alongside the inspirational Imtiaz Sipra—that our camaraderie deepened. I had been entrusted with their company, and being among them was a continuous learning curve. Farooq was a chain smoker; each drag seemed to take him deeper into some private universe, the smoke curling around his thoughts as they travelled unbroken.

Later, when I was working as a cricket analyst with the Pakistan team in New Zealand, Farooq joined as the team's Media Manager. It was an experience both enriching and unforgettable. He was in a league of his own. His talents were immense, his personality forceful—sometimes overbearing, but always compelling. His writings were fearless, unflinching, at times rancorous, but always worth reading; his voice carried the resonance of authority; his vocabulary was precise and vivid; his humour was dry and perfectly timed; his generosity could be overwhelming; his hospitality was unabashedly Eastern; his criticism was forthright, at times stinging, but never without the aim of betterment.

The Voice Behind Hockey's Golden Era

I have had the pleasure, the honour, and the rare privilege of knowing Farooq Mazhar for a while—our paths most often crossing under the hum of floodlights, in the liminal hours of cricket coverage when the game had paused but the conversation had not. Yet my relationship with him began much earlier, not with a handshake, but through the low-pitched cadence of his voice. As a teenager in the 1980s, hockey telecasts were not just broadcasts; they were events, small carnivals in drawing rooms across the country. And the India–Pakistan matches—those contests where history and emotion poured into every movement—were less sport and more theatre. In that theatre, Farooq was both narrator and stagehand, speaking softly yet decisively into the national bloodstream. His words were not just descriptions; they were alchemy, turning statistics into story, motion into meaning.

It was through him that I came to know the silhouettes of Hassan Sardar, Hanif Khan, Samiullah, Manzoor Junior, Salahuddin, and Kaleemullah—not as distant heroes but as men with technique, habits, and a certain ineffable grace. He gave their flicks, dribbles, and goals the weight of literature, and in doing so, made us feel the poetry in their sweat.

The Final Tour and Signs of Illness

Years later, in New Zealand, the image of Farooq was altered but not diminished. The cough had begun to punctuate his sentences, and in one of those unguarded interludes between matches, he mentioned—without drama—that he was coughing up blood and carrying a low-grade fever. To a clinician, the words were cause for concern; to Farooq, they were simply another item on a long list of inconveniences. He was a chain smoker, yes, but also a chain thinker—his mind forever circling sport, country, and the next sentence he might write. He looked unwell, and the tour's grind deepened the periorbital darkness. Yet he was there, because he had said yes. That was the patriot in him—not one who waves a flag, but one who shows up, even when the body pleads otherwise.

There was a side plot to that tour, almost comic in its persistence. Farooq's bags had not arrived with the team's luggage, and for days he lived on the modest airline allowance that passes for compensation. We dined together in Christchurch and Wellington, and there were evenings in the company of Chisty Mujahid, Faqir Syed Aizazuddin, and Javed Miandad—sessions in which time dissolved into anecdotes, laughter, and the slow burn of nostalgia. Even as his health betrayed him, Farooq's spirit remained as it had always been: dry-witted, clear-eyed, relentlessly engaged. He thought always of Pakistan, of its cricket, of its place in the broader tapestry of sport.

A Partnership in Preserving Memory

My respect for Farooq was deep, and it extended to his wife, Khalida Mazhar—herself an eminent producer at Pakistan Television, another custodian of our sporting memory. Together, they represented something rare: a belief that sport is not just to be played or watched, but to be remembered, to be preserved in words and images, so that it survives the erosion of time.Farooq, in his voice, in his writing, in the way he held a room, made you feel that sport was more than competition. It was, and always had been, a repository of our collective longing. And in his presence, you could almost believe that memory itself was a kind of patriotism.

The Final Diagnosis and Defiant Spirit

And when the final whistle sounds in the theatre of life, let the last echo be his—measured, wise, unflinching—a voice that reminded us, if only for a while, that even in play we draw nearest to the truth. He was diagnosed to have bronchogenic carcinoma. By the time the verdict came, it had already metastasized into his bones. The disease had been at work quietly, without fanfare, and now it had claimed almost all the ground there was to take. He knew, in those closing phases, that the days ahead were few, that the days left were thin. And yet, he carried on with the stubborn poise of a man unwilling to bow too soon—savouring a drink or two, relishing the heat of spicy food at Little India in Wellington, as if each sip and bite were a small rebellion against the inevitable.

A Legendary Career Spanning Decades

His journey began in 1959, in the pages of the then-celebrated Sportstimes, as a young man found his voice among columns and deadlines. From there, he moved to the Pakistan Times, where he stood not just as a sports reporter but as a chronicler of moments that would outlive the games themselves. He was among the rare few in the world to cover nine editions of the Olympic Games—on air, in print, through the lens—each one another brushstroke in a career that stretched across generations. And he was not bound by the lines of sport alone. In politics, his mind was sharp, his vision unclouded; his commentary clear enough to cut through the smoke. It made him not just respected but admired, even adored, by those who hung on his words.

The Hockey Oracle

In hockey, his counsel became legend. As President of the International Hockey Sports Writers Association, under the aegis of the FIH, he carried a depth of knowledge so complete, so free of bias, that the game's most powerful men—General Musa Khan, Air Marshal Nur Khan, Arif Ali Khan Abbasi—sought his advice. In those meetings, he was not just a journalist, but a keeper of the game's conscience, a man whose grasp of its soul was as sure as his command of its story.

The Final Journey

The news of Farooq Mazhar's passing fell like sudden dusk across the hearts of Pakistani journalists and writers scattered through North America; an evening shadow that dimmed the memory of a man they called not merely colleague, but dost—brother, guide, kindred spirit. In Houston, where the veteran sports chronicler had gone to seek specialist care, sorrow gathered quietly in doorways and over small tables—soft, communal, unshowy.

The loss of Farooq Mazhar, 65, revered hockey commentator and former sports editor of Pakistan Times, a journalist at The Sun and The News, was not simply the departure of a voice; it was the silencing of a legacy, carefully stitched into the fabric of Pakistan's sporting memory. For decades, his sentences made stadiums breathe and turned matches into recollection. Now the voice was still, and in its stillness a profound quiet remained.

A Grief Born of Love

Those who moved within the circles of broadcasting and print mourned him with a disbelief that spoke of love. I did not believe Farooq would leave us so soon. The grief did not shout; it lingered—shaped by genuine respect and the tenderness reserved for an elder whose hand steadied the younger. Mid-flight to Houston, he suffered a stroke and paralysis aboard a Pakistan International Airlines journey; the plane, diverted to Bahrain, became an unexpected last stop. In a foreign hospital he surrendered, at last, to the illnesses he had fought for years—lung cancer chief among them. Even before the end, his voice had thinned; yet within its frailty lived the rhythm of fields, rinks, and arenas he had animated for generations.

Only days earlier, he had returned from accompanying Pakistan's team in New Zealand. Those who saw him spoke of a man visibly worn yet stubbornly resolute, unwilling to loosen his grip on the work he loved, whatever the price. In death, as in life, Farooq bridged distances and bound affections—from Lahore's playing fields to Houston's quiet libraries, from Karachi's newsroom corridors to Toronto's community tables. He belonged to that rare fraternity of journalists whose words were not just written, but lived.

The Alpha and the Mentor

And yet, beyond the microphone's hush and the print's quiet permanence, Farooq Mazhar stood as a figure carved in sure lines—an alpha in bearing, steadfast in conviction, carrying himself with the easy certainty of one who knew his place in the order of things. As a journalist, his presence was complete: fearless in judgement, exact in expression, a voice that would not—could not—be overlooked in any room where words mattered. But the man outstripped the profession. As a mentor, he gave of his time without measure, scattered his learning with unguarded generosity, and held to the high standards that lifted those who sought his counsel. There was tempered steel in what he taught, yet always a human warmth in the giving of it; a rare poise that made his protégés believe not only in their craft, but in the worth of their own voices. To know him was to see that strength lies not in the volume of one's speech, but in the quiet weight of truths one dares to pass on.