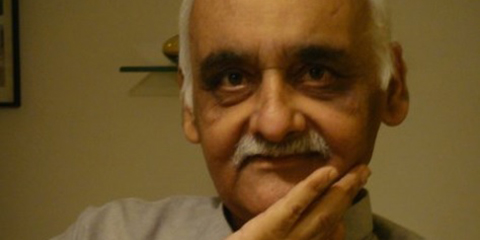

From airline pilot to cricket historian: The extraordinary life of Gul Hameed Bhatti

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

ISLAMABAD — Some men leave their mark not by the noise they make, but by the silences they dignify. Gul Hameed Bhatti was one such man, a figure who personified the strange alchemy of humility and magnitude. He was not flamboyant, nor did he ever seek the stage, yet wherever cricket's past was summoned, his presence arrived unbidden, like a memory folded into the very composition of the game.

The Voice That Changed Everything

I remember him first not as a face but as a voice down the telephone line. At a time when my own life was caught in competing flows, the sterile routines of hospital wards and the flickering rehearsals of television studios, he intruded with the gentle force of inevitability. His words were not a suggestion but a command, softly issued yet impossible to resist. 'You write better than you speak on television. Send something. Sundays, at least.' That was Bhatti in essence: a man who saw the essence of you before you had grasped it yourself, who recognised in you what you had half-forgotten, and who compelled you to reclaim it.

The Paradox of Genius and Humility

When we finally met, the paradox of him became clearer. He was vast, yet unassuming. He carried intelligence like a lamp in the pocket, lit only when needed. He never overwhelmed a room, but in conversation his depth unfolded, and you felt the reassuring weight of someone who had not only watched cricket but carried it inside him. Matches were not anecdotes for him, they were parables; scorecards not lists of numbers, but genealogies of a nation's game. His memory, precise and alive, could conjure a forgotten over or an obscure dismissal as vividly as if it had occurred that very morning.

Architect of Pakistan Cricket History

And yet, with all his knowledge, there was no vanity. When I embarked on the monumental task of compiling the Official History of Pakistan Cricket, it was Bhatti who quietly drew the map. He pointed me towards the Dawn archives, connected me with Abid Ali Kazi, and designed forms for players past and departed so that history might be retrieved from the oblivion of time. He was not just an adviser; he was a companion on that long vigil, a steady voice on the telephone urging patience, accuracy, fidelity. Those thousands of pages, darned together with sweat and silence, carry his unseen imprint, his invisible but indelible guidance.

The Philosophy of Cricket Writing

Bhatti's impact was not confined to the page. He was an ethic, a philosophy. He taught that cricket writing was not performance but stewardship; not about declaring opinions in haste, but preserving memory with care. He reminded us that truth lay not in rhetoric but in record, not in noise but in detail. He could laugh heartily, joke generously, and yet in the same breath remind you of the sacredness of a scorecard, the sanctity of fact. His greatness was not that he was a statistician, but that he transformed statistics into memory, memory into literature.

From Pilot to Cricket's Greatest Archivist

A man like Bhatti does not die when his body fails; he lingers in the footnotes, in the scorebooks, in the quiet resolve of those who follow. His was not a life spent in the spotlight, but in the steady glow of devotion. And so, when we remember him, we do not remember noise or spectacle. We remember patience. We remember fidelity. We remember cricket, preserved whole, because Gul Hameed Bhatti once cared enough to make it so.

There are men who, in their devotion, remind us that cricket is not just played with bat and ball, but lived through the imagination, through words and numbers, through memory kept alive by the archivist's pen. Gul Hameed Bhatti was one such pilgrim, a figure who turned from the secure avenues of life, from cockpits and corporate offices, into the winding and uncertain alleyways of cricket journalism. It is the kind of surrender that resembles poetry itself: inexplicable, irrational, yet utterly inevitable.

The Journey from Aviation to Cricket Documentation

Bhatti's story begins not in the pavilion but in the wider theatre of ambition. He was once an airline pilot, trained to command the skies with precision and calm. The pilot's craft is a matter of control, instruments, coordinates, and the quiet authority of navigation. Later, he took senior charge at the Trade Development Corporation of Pakistan, another position of dignity and safety, one that promised structure and a career wrought from steady increments. But for Bhatti, these employments were interludes, like preludes in a symphony before the real music begins. For his inner calling lay elsewhere, with cricket, a game that pulled him with the quiet insistence of destiny.

The Sacred Calling of Cricket Statistics

And so he left those vocations, exchanged certainty for uncertainty, and chose to make his life in cricket writing. Not the writing of florid opinions or the instant judgement of performances, but the writing that required patience, vigilance, and fidelity to truth. In an age when most around him were possessed by rhetoric, Bhatti was possessed by accuracy. He became, in time, the grand statistician of Pakistan cricket, its unerring keeper of records, its raconteur who would not allow a single scorecard to be lost to negligence or fabrication.

The Man Beyond the Numbers

Yet it would be unfair to picture him only as the dry accountant of cricket's numbers. His personality was not bound in ledgers and dusty files. He was large of spirit, genial in company, fond of good food and convivial conversation. His humor was quick, his heart expansive. One remembers him laughing as heartily as he calculated, eating as generously as he compiled. He carried the aura of a man who understood that life and cricket were to be savored in equal measure, both as sustenance and as song.

The Religious Devotion to Cricket's Truth

Still, there was something in him that resembled the cloistered, the ascetic. To sit for hours over fading scorebooks, to retrieve lost details of forgotten domestic matches, to write in patient longhand or bang away at his typewriter until clarity emerged, this was devotion that verged on the religious. When others misremembered or fabricated, Bhatti's fidelity to fact was immovable. He would rather walk away from a conversation than indulge in speculation. In this, he was a guardian of cricket's integrity, for he believed the truth of the game lived in its records.

Preserving Pakistan's Cricket Heritage

And what records he preserved! Pakistan's first-class scorecards of the 1970s and 1980s, scattered and uncollected, were drawn together under his initiative. With the help of kindred spirits like Abid Ali Kazi and Nauman Badr, he undertook the painstaking task of filling in the gaps of the nation's cricketing annals. It was a service not always recognized in his homeland, but acknowledged abroad, even in Wisden and by Bill Frindall himself. But recognition mattered little to Bhatti. He did it because it was necessary. After all, cricket deserved no less.

The Paradox of Expertise and Humility

What is striking, when we remember him now, is the paradox of his character. He, who knew so much, shied from calling himself an expert. He, who was the ultimate custodian of cricket facts, often preferred silence when asked for opinions. He was at once imposing, in physique, in knowledge, and yet self-effacing, content to remain in the background while others pronounced. But quietly, by sheer accumulation of work and presence, he became the doyen of Pakistan's cricket writers, its unchallenged leader among statisticians.

A Life Lived for Meaning, Not Money

That he gave up piloting aircraft, that he stepped away from senior posts in government service, tells us something profound about his temperament. He sought not rank but relevance, not money but meaning. Cricket, with its blend of artistry and numbers, of drama and discipline, offered him both a mirror and a mission. And so he gave himself to it, unreservedly, leaving behind the security of other lives for the uncertainty of this one.

Legacy That Lives On

Today, more than 15 years after his passing, Bhatti's presence still lingers. It lingers in the statistics of Pakistan cricket, in the mentorship he offered young writers, in the laughter remembered by his friends, in the generosity of his table. He was, above all, a man who lived as if cricket was not just a game but a calling, and his vocation was to ensure that its truth would not be lost.

In him, numbers became narrative, records became remembrance, and journalism became a form of fidelity. He left the skies and the offices of state, yes, but he gained the immortality that belongs to those who serve a game with love untainted by self. Gul Hameed Bhatti, the pilgrim of cricket's numbers, remains Pakistan cricket's most unlikely, and perhaps most enduring, hero.

The Essential Thread in Pakistan Cricket's Tapestry

There are men whose shadows loom large on a game, not because they ever played it, nor because they had the lungs of commentary or the shoulders of administration, but because they recounted it with such persistence, with such devotion, that the game itself bent a little to make space for them. Gul Hameed Bhatti was one of those rare men. In Pakistan cricket, his name is mentioned in the same breath as the first-class cricketers, the Test greats, and the administrators who tried, often clumsily, to steward the sport. He did not bowl a ball in anger for Karachi or Lahore, did not feather a cover drive on a sun-scorched pitch in Multan, did not stand at slip while Fazal Mahmood grumbled. Yet, he documented all of it, and in doing so, he became essential.

If Pakistan cricket is a patchwork quilt tacked from scorecards, anecdotes, and fading photographs, then Bhatti was one of its most patient weavers. His journalism, his statistics, his mentorship, his wit, his appetite, all coalesced into a presence that still, more than a decade after his death, is felt whenever cricket's past in Pakistan is summoned.

The Three Acts of a Distinguished Career

Bhatti's career had a flow to it, almost like a four-act play. The first act began at The Cricketer Pakistan, where he would spend the better part of 15 years, save for a short detour in the mid-80s. It was there that his name began to carry weight, the byline that meant authority, fact, detail, trust. The second act was the experiment: Cricket Star, a magazine launched with his childhood friend Abbas Kazim. Born in Lahore with optimism and that peculiar Lahori bravado, if Karachi could do it, why not us? The magazine flickered for just over a year before fading. A lesser man might have sulked, but Bhatti simply returned to The Cricketer as if he had stepped out for a cup of tea.

The third act was when the Jang Group came calling. They were launching The News International, an English-language daily, and they needed someone to helm sports. Bhatti became not only the Sports Editor but eventually Editor of the entire paper, and later, Group Sports Editor of Jang's publications. His stature only grew, though he remained, characteristically, unpretentious about it.

The Lifelong Mission of Statistical Accuracy

And then the fourth act, which overlapped with the rest: his statisticianship, his lifelong pursuit of scorecards, records, facts. Here, Bhatti stood unmatched. He, alongside Abid Ali Kazi and Nauman Badr, embarked on the thankless odyssey of collecting missing domestic scorecards from the 70s and 80s. It was a labor of love, endless hours poring over scraps of information, scorebooks jealously guarded by the late Ghulam Mustafa Khan, bits of lore that had to be cross-examined. The work was recognized by Wisden and by Bill Frindall, England's famed scorer, but in Pakistan, it barely registered beyond the small fraternity of obsessives. And yet, Bhatti never complained. He never bragged. He simply kept going.

The Authority That Came from Truth

Here was the paradox: in a land overflowing with half-baked experts and loudly opinionated uncles, Gul Hameed Bhatti had more cricket knowledge than almost anyone else. Yet, he hated talking about cricket in public. Ask him about an ongoing match, and his face would crumple with boredom. He couldn't care less who should bat at number three or whether Waqar was swinging it enough. What he did care about was facts. The sanctity of a scorecard, the precision of a statistic, the truth of history.

When one gentleman, Habibullah Naz, tried to rewrite himself into Pakistan's cricketing history, claiming he had once been part of the national squad in the 1950s, Bhatti dismantled him in print. No anger, no flourish, just the cold, clinical dissection of a man who had numbers on his side. The rebuttal was so thorough that no reply ever came. That was Bhatti's authority: absolute, irrefutable, quietly devastating.

The Joy of Life Beyond Cricket

To imagine Bhatti only as a dry statistician is to miss the joy of the man. He was, like most Lahoris, a devoted foodie. Karachi never cured him of his Lahore palate. His eyes lit up at the mention of firni thootis, and he could turn a casual lunch into an eating marathon.

He often prowled the streets of Burns Road, Lakshmi Chowk, and Abbott Road, devouring kebabs, Kashmiri chai, and sweets with the gusto of a man who believed meals were as important as milestones. In the 80s, he cruised around Karachi in what he called 'the world's only chauffeur-driven Suzuki Custom," piloted by Jabbar, a taciturn driver who also lugged Bhatti's typewriter and once competed alongside him in a poori-eating contest at Tooso's in Bahadurabad. Their joint tally: seventeen.

The Shadow of Loss

There were Pictionary nights at his house, midnight pizza raids, and advice that could only be Bhatti's. After Razia's passing, it was as though Bhatti's spirit had been cleaved in two. The man who had once carried laughter in his eyes and vigour in his step became, instead, a shadow gently trailing behind memory. He had survived cancer, yes, but what he could not survive was the silence Razia left behind. Medicines lay neglected on his table, anti-hypertensives dismissed with the wave of a hand, as though discipline in health was a concession he refused to grant a world that had already taken too much from him. It was this rebellion, quiet but costly, that one day betrayed him in the form of a cerebral haemorrhage, and with it, we lost him.

Building Community Through Cricket Statistics

In 1984, Bhatti founded PACS, the Pakistan Association of Cricket Statisticians, which later morphed into PACSS, adding scorers to the mix. Its first meeting, at Bhatti's Gulnar Apartments residence, had all the earnestness of a start-up and all the flavors of a dawat. Abid Ali Kazi, Masood Hamid of Dawn, and Abdullah Kadwani were there. Yes, we discussed cricket statistics, but we also devoured homemade shami kababs and French toast. That was the Bhatti way: work and food, numbers and laughter, never separated.

The Unexpected Actor

And then there was Bhatti, the actor, yes, the same man who was allergic to public cricket conversations once stepped into the glare of television. In Nadan Nadia, opposite none other than Babra Sharif, he played Mateen Sahib. He wasn't bad either; his natural presence carried him through. Few knew that even as a teenager, he had made brief cameos in Pakistani films. His personal library, at his Clifton Garden apartment, revealed the secret: alongside the mountain of cricket books sat an equally large collection of VHS cassettes. Cricket and cinema, side by side, like parallel loves.

The Mentor Who Shaped Generations

If numbers were his fortress, mentorship was his gift. He believed in youth, in giving them a shot, in letting them write and stumble and learn. Many of Pakistan's cricket correspondents, Fareshteh Aslam, Sohaib Alvi, Khalid H Khan, Khalid Mehmood, Zahid Zia Cheema, and I, found early encouragement under his watch. His edits were sharp but always laced with humor.

The Personal Loss That Changed Everything

And there was family. His wife, the formidable journalist Razia Bhatti of Newsline, and his children, Kamil and Sara, whom he adored. Razia's sudden passing shook him to the core, left him quieter, frailer. When I last saw him at Liaquat National Hospital, he was subdued. To rouse him, Abid Kazi cracked all sorts of jokes. The response was immediate: the old Bhatti grin, a counter-joke, the sparkle of mischief.

A Life of Beautiful Contradictions

Gul Hameed Bhatti's life reads like an oxymoron: a man who knew more cricket than most but cared little for opinion, a foodie who turned meals into folklore, a statistician who elevated numbers into literature, an editor who raised voices beyond his own, an actor who once held his own with Babra Sharif but shunned the limelight otherwise. He was, at once, immense and ordinary, complex and simple. His authority came not from self-assertion but from diligence. His presence in Pakistan cricket is not in scorecards alone but in the people he fed — with food, with opportunity, with kindness.

The Greatest Contributor Outside the Field

Lists of great contributors to Pakistan cricket rarely accommodate men outside the field. But if you widen the gaze, if you include those who kept the records, who built the scaffolding on which memory rests, then Gul Hameed Bhatti must surely sit at the top. Perhaps not batting, not bowling, but keeping score, always keeping score, so that the game could live on in truth.

Making Statistics Dance and Sing

Figures were always fun with him. He made them dance, sing, and share stories no one else had heard. Figures are Fun with GHB was the column that became an initiation rite for many of us, an entry ticket into the labyrinth of cricket. For us staring blankly at the chaos of averages and aggregates, he gave the keys: bowlers under thirty were good, batsmen over forty were better, and thus the game unfurled. He was our statistician, yes, but the title barely covered him. For Gul Hameed Bhatti was no sterile compiler of numbers. He breathed life into them, gave them wit, humour, context, and history. He was the guru of stats and infinitely better company. When he finally did encounter Statsguru, he joked it was passable, perhaps even bearable for an evening's companionship. Such was his lightness, his ease with even the gravest of obsessions.

The Voice of Reason in Cricket Chaos

What is lost in calling him only a statistician is his prose, elegant, understated, tinged with Lahori humour, capable of extracting laughter where none should exist. He knew Pakistan cricket more intimately than anyone who walked the corridors of Gaddafi Stadium. He loved domestic cricket fiercely, as though it was his own child, ill-treated and overlooked, yet the foundation of all else. He might have sat on the Board, might have brought sanity to their halls of chaos, but perhaps it was best he never did. Even the purest spirits risk corruption there.

At workshops and seminars, he was always present, his voice measured amidst the cacophony of retired cricketers peddling their quick-fix remedies. He never shouted, never raged. He spoke softly, rationally, with unflinching clarity: take ownership of domestic cricket, give it status, give it dignity, stop tinkering with it. His voice was not heeded.

The Encyclopedia of Pakistan Cricket

That silence, in truth, speaks more of them than of him. He wrote endlessly to Cricinfo, tut-tutting us gently over misspelled names, wrong dates of birth, and misplaced places of origin. He was, as Waheed Khan once called him, an encyclopaedia of Pakistan cricket. His database, vast and meticulous, was said to rival any institution. One shudders to think of its loss.

A Renaissance Man of Many Talents

Yet Gul Hameed was far more than cricket. A qualified pilot who once flew 45 hours before grounding himself, a PR man, an actor in a TV play, a singer of songs, a columnist of cuisine. His life was a maze of detours, each one taken with humility. He was also the husband of Razia Bhatti, herself a legend of journalism. When she died in 1996, a little of him went with her. He continued, but dimmer, quieter, though never diminished in dignity.

The Warmth That Defined Him

I knew him as warmth personified, a man whose smiles came easily, whose laughter never excluded. Meeting him first in the mid-nineties, I was nervous, tongue-tied. I have interviewed captains and kings, but none induced that awe. Yet Bhatti Sahab disarmed me in minutes, with his serenity, his humour, his cricket tales that flowed like gentle rivers. He spoke of missing classes to watch Shafqat Rana bat, of college matches that shaped him. He loved cricket with the devotion of a believer.

The Final Chapter

In the end, cricket and its figures will not be as much fun without him. We knew he was ill, retreating into silence after repeated strokes. And yet, he summoned the strength to attend Newsline's 20th anniversary, his Razia's magazine, his anchor. It was a final gift, a glimpse of resilience. A few months later, on February 4th, 2010, the inevitable came. His friends and colleagues were prepared, and still they were not. The grief was deep because such people are not just lost; they leave absences that nothing fills.

Remembering the Complete Man

His brother remembered him as a boy sketching cricket matches on sheets of paper, inventing entire games in ink when he was forbidden to play on the field. A would-be doctor who became a pilot, a pilot who became a journalist, a journalist who became a legend. Others remembered his laughter, his pranks, his stubborn decency. He was always at the centre of the room, never demanding it, simply deserving it. He was boss, mentor, colleague, friend. He was a father, husband, and brother. He was Lahore humour, Sargodha kindness, and Pakistan cricket's beating statistical heart. Gul Hameed Bhatti may have been buried that day, but cricket will forever keep him alive, every time numbers whisper their secret stories, every time figures are fun.

The Father Figure of Cricket Journalism

'Aray is ko kya pata, yeh to bacha hai …' he would chuckle, half a rebuke, half a benediction, whenever a young colleague fumbled with a question about an old Pakistani film. Often, he had the answer; sometimes, he did not. But his company itself was the answer. For in Gul Hameed Bhatti, you found not merely a colleague or a senior, but something deeper: a father-figure, a mentor who did not so much instruct as embrace, who laughed after advice, who stood by you when the profession threatened to swallow you whole.

The Actor Who Never Sought Fame

We remember him in many guises, but one lingers, the child-actor who once appeared as Mateen Sahib in Nadaan Nadia. He dismissed it with characteristic understatement, calling himself only a 'seasoned campaigner.' Few knew that his first film debut came in 1949, when he was six months old, his father's position in the police connecting him to the young, restless world of Pakistan. By the time he turned ten, he had abandoned cinema, walked away from theatre, and later, in the 1990s, dabbled again on stage, though never seeking recognition for it.

'The last thing I want to be remembered for is acting,' he said. He would often joke about mortality too, masking frailty with his Lahori humour. 'Zyada se zyada kya hoga … mar jaoonga.' That was his refrain when he pressed coins into the hands of peons for samosas. He had cancer; high blood pressure. He would smile and say he was unwell not for what he had done, but for what he had not. And now that he has gone, it is difficult not to believe in the old maxim that the good are summoned first.

A Legacy That Transcends Death

In his final years, his children created a small space on Facebook to share updates about his health. Strangers, admirers, those who knew him only by his words, filled it with grief when he passed. They mourned not just a father or a journalist but a guardian of truth, an anchor of cricket's memory. His death, they said, was a loss not only for family or friends but for a whole legion who had read him, trusted him, leaned on him.

The Professional Who Never Compromised

For Bhatti was never just a statistician. He was a pilot once, flying commercially for Pakistan International Airlines between 1968 and 1971. But his passion, irresistible and consuming, was cricket. To sate it, he gave up wings for words. He chronicled the game with the obsession of a lover and the discipline of a craftsman. His white hair, the scar on his neck, the measured eloquence of his speech, these became markers of a man who wore his suffering lightly, even as he served as Group Sports Editor of The News until the very end.

The Upright Journalist in a Volatile World

He was eccentric, vibrant, charming, sometimes arrogant, and often judicious. But always, always upright. A thoroughbred journalist, he had the rare gift of surviving in a volatile, power-stricken world without yielding his conscience. Born in 1948, raised on the inter-collegiate rivalries of Government College and Islamia at Lahore's University Ground, he began by sketching scorecards for the BCCP. His first great assignment came during the Pakistan-Australia Test of 1959–60 at Gaddafi Stadium. From there, a future stretched out, setting up The Cricketer Pakistan, forming the Association of Statisticians and Historians, producing issue after issue of Facts and Figures Quarterly despite the scarcity of data and money.

The Man Behind the Statistics

Behind the statistics was always the man, a deeply sensitive one. His great love, Razia Bhatti, herself a colossus of journalism, passed in 1996, and with her went a part of his light. He never recovered fully. He lingered, he fought, he suffered strokes, he withered. On February 5th, 2010, the second stroke carried him away. Those who never met him still felt they knew him. They recognised him in old magazines, in carefully copied scorecards, in notes made by schoolboys tracing his columns by hand in libraries. For a generation, he was the maseeha of numbers, the keeper of Pakistan's cricketing memory.

When the news of his passing came, it felt like the silencing of a great clock, one that had ticked faithfully for decades, counting not just runs and wickets, but the very pulse of a nation's game.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has been the highest in ratings and acclaim.