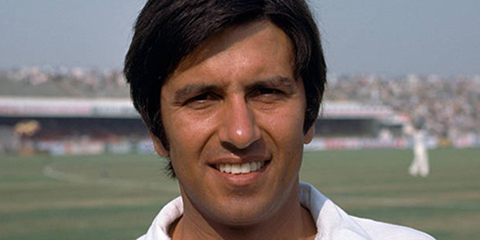

Majid Khan: The majestic cricket legend who redefined elegant batting and broadcasting

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

I first set foot upon the path of sports journalism in 1988, though it was not until 1992–93 that I was momentarily lit upon the small stage of television. The late Jamshed Farshori extended the invitation, Aliya Rasheed presided, and, almost by chance, the occasion became my own. Then silence descended—the screen withdrew me into its shadows—until 1996, when Syed Talat Hussain, having paraded a gallery of journalists on his PTV News show 'Sawery Sawery, beckoned me forward. I went, and immediately there was a harmony with a sound true and rare.

The late Naveed Zafar, Director of Current Affairs, and Syed Zahoor Mehdi, Executive Producer, soon called me to an audition. Yet with the nonchalance television often assumes when about to change a life, they thrust me directly into the live furnace of broadcast. Thus, in a moment of improvisation, my career truly began.

From Childhood Hero to Broadcasting Mentor

From that instant, fate placed me in the company of Majid Jahangir Khan, Director of Sports of PTV—once my childhood hero, now my mentor, my guide, the steadying hand upon the shoulder. He became to me what an elder artist is to an apprentice, teacher, encourager, the unseen sculptor of a younger man's craft.

It was a dream, almost impudent in its fortune: the idol of my youth stood before me, elegant still, regal of carriage, a mind teeming with invention. It was Majid who altered the very dynamics of sports broadcasting in Pakistan. With his imagination and unyielding integrity, he conjured the pre- and post-match transmission, an idea so obvious in retrospect, yet then unprecedented. I was summoned to host these new programmes, and the medium itself seemed to turn on its axis.

Majid Khan was never content to be an administrator, nor was he only a superior by hierarchy. He was an exemplar of probity and candour, inventive in thought, graceful in deed, and unfailingly creative. Whatever little I have learnt of broadcasting, whatever understanding I claim of its art, is indebted almost entirely to him.

The Early Life of Pakistan's Cricket Royalty in Pre-Partition Punjab

Majid Khan was born on 28 September 1946 in Ludhiana, Punjab, beneath skies not yet severed by Partition, before the maps were torn and memories rearranged by history's ruthless hands. Out of that land, fractured and uncertain, arose the man whom the British press named "Majestic Khan", and for once, journalism did not overreach itself. The title clung to him naturally, as a robe sits upon a prince.

At his best, Majid was never only a collector of runs. He turned batting into something rarer: an exercise in line and balance, in poise and economy, as though aesthetics itself had chosen him for its envoy. He placed his strokes; he did not strike them. His timing was his creed, elegance his instrument, and both were used not for ornament but for inevitability. To watch him was to learn that serenity can exist even amidst chaos. Indeed, the more furious the tempest, the calmer Majid appeared; and by some paradox, that very calm heightened the drama of the storm.

Facing Cricket's Greatest Fast Bowlers with Unmatched Grace

Against the furies of the 1970s—the merciless quartets of the West Indies, the sulphurous thunder of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson—Majid did not only endure; he flourished. Where others recoiled in self-preservation, he stood as though untouched by menace, as if pace itself bent into deference before him. His bat moved not in panic but in poise, strokes flowering like sudden music upon a field where violence was expected but beauty appeared instead.

To the statisticians, he left 3,931 runs in 63 Tests, adorned with eight centuries, and more than 27,000 in first-class cricket. Yet numbers, always the bluntest instruments, fail to capture his presence. His was not a career concluded in the usual punctuation of farewells; his last Test at Lahore in 1983, his last one-day at Old Trafford in 1982, were not so much endings as dissolves into memory. Cricketers such as Majid never retire—they remain, lingering, eternal, in remembered grace.

The Khan Family Cricket Dynasty and Historic Bloodlines

Majid's life was bound to cricket before his first cry. His father, Dr Jahangir Khan, had once worn India's colours, before history's cartographers tore one land into two. His cousin, Imran Khan, would later inherit Pakistan's captaincy and charisma, before exchanging flannels for the vestments of politics. Majid himself began with the ferocity of pace, until injury curved his path into the subtler arts of spin, and then—by destiny's design—into the true inheritance of bat and blade.

No geography confined him. He wore the colours of Glamorgan in Wales, Queensland in Australia, and the many provinces of Pakistan—PIA, Rawalpindi, Lahore, Punjab. Glamorgan in 1969 opened the door to Cambridge, where history was read by day and written by bat in summer's air. At Cambridge, he rose to captaincy and in 1971 achieved what few could imagine, leading the University to victory over a touring Pakistan side, his own countrymen, a feat unrepeated since 1927. And in 1970 at Lord's, he shaped a double century against Oxford, a triumph that inscribed him into both the cloisters of academia and the annals of cricket.

The Legendary Jahangir Khan and the Sparrow at Lord's

The name Jahangir Khan itself bore its fables. In 1936, bowling for Cambridge at Fenner's, he delivered a ball that felled a bird in mid-flight—an accident so rare that the sparrow rests still in the MCC Museum, a reminder that cricket, too, submits to fate's eccentric footnotes. Years later, when Majid stood upon the brink of national selection, his father, Jahangir—then Chief Selector of the BCCP, resigned in silence, choosing honour above office. Thus, in the tale of Majid Khan, cricket was never only a profession but an inheritance: intertwined sacrifice, honour, and those mythic accidents of fate which lend the game its lyrics.

Historic Test Cricket Debut and Century Before Lunch Achievement

Majid's Test journey began in 1964, at the National Stadium in Karachi, against Australia. He was nineteen, slender, almost willowy, a figure more of refinement than of sinew, as though some young aristocrat had wandered into the arena by inheritance rather than intent. Yet when at last he laid his bat aside, he had written his name into one of cricket's rarest illuminated registers: one of only six men—Victor Trumper, Charlie Macartney, Sir Donald Bradman, David Warner, Shikhar Dhawan, the others, who ever reached a hundred before lunch on the opening day of a Test.

It was Karachi, 1976–77, against New Zealand. The crowd did not witness batting in its crude sense; they saw theatre. His strokes, glides, cuts, pulls, spoke not of force but inevitability, verses written across the green parchment of morning. By the luncheon interval, he was 108 not out from 78 balls, a figure out of poetry rather than mere sport. Cricket was not a contest; it was art distilled into the whiteness of flannels.

Pakistan's First One-Day International Century Pioneer

And long before that remembered splendour, he had touched immortality in the game's briefer, brasher form. His one-day debut came at Christchurch in 1973, and a year later at Nottingham, he inscribed another first, Pakistan's inaugural one-day century. Always, Majid was opening new doors, turning numbers into narrative.

Post-Playing Cricket Administration Career and Corruption Charges

When, in the fullness of time, he laid down the bat, he did not depart from cricket's orbit. Instead, he moved among its constellations—Chief Selector in 1993, Chief Executive of the PCB in its unsettled mid-1990s. In 1995, he served as a match referee, and in 1999, during the glare of a World Cup, he spoke with truth, charging Pakistan's game with corruption. Sarfraz Nawaz stood by him; the rest, as so often in Pakistan cricket, fell silent. His resignation left the wound unhealed, a bruise still visible on the conscience of the game.

Now he lives in Islamabad, apart from the clamour. Yet memory refuses release. He remains Majestic Khan—the batsman who once turned fast bowling into mere ornament, who made cricket beautiful simply by taking guard.

The Aristocratic Elegance That Defined Majid Khan's Batting Style

He was presence itself, languid grace, unremitting poise embodied, collar upturned in gentle defiance, strokes effortless, as if lent to him from some higher realm. To see him bat was to recall that cricket, beneath its ledgers and dynamics, could still be art. On his day, he was incomparable. He bent the ball to his will: eyes quick, feet flashing, wrists supple as silk. Elegance was his creed. Peter West quipped that the only inelegant thing about Majid was his floppy hat, everything else, from his stride to his shirt, was immaculate. His centuries dazzled like fireworks against night skies, even as his failures carried the fragrance of unfinished verse. But when the gems came, they left an afterglow lingering beyond stumps.

Memorable Cricket Innings That Became Legendary Vignettes

There was the double hundred for Punjab University, a 61-minute hundred for Glamorgan beneath Welsh skies, centuries in Karachi and Georgetown against the fire of the West Indies, the 112 at Christchurch against Richard Hadlee and Lance Cairns, achieved with the air of one who had always been seated in three figures. These were not innings; they were vignettes, unforgettable entries in cricket's anthology.

The Khan Family Cricket Lineage Across Generations

Majid, in full flow, was majesty incarnate. His very name carried regality. The bloodline confirmed it: Jahangir Khan, his father, had played India's first Test in 1932 and once felled a sparrow in mid-flight at Lord's; Javed Burki and Imran Khan were his cousins; his son Bazid, the third generation of Lahore's Khans, continued the lineage. The family equalled record set by Sir George Headley, Ron Headley & Dean Headley. Jahangir schooled his son not in mechanics, but in joy. That joy remained even when Majid was asked to temper brilliance with dependability. His strokes shimmered always.

From St Anthony's to Test Cricket Excellence

Too small at St Anthony's, undeniable at Aitchison, by 13, he was in the first eleven. His first-class debut was legend itself—111 not out, and six wickets for 67. His father had also scored a hundred & picked eight in an innings on his maiden appearance.

At 18, he entered Pakistan's Test side as a raw all-rounder, dismissing Bill Lawry with a bouncer. The bowler faded; the batsman, the true inheritance, emerged. By 1967, he was opening in England.

The Glamorgan Years and Welsh Cricket Folklore

At Swansea, 147 not out in 89 minutes, 13 sixes scattered, Roger Davis was punished in a single over. Wales embraced him, called him Kipper, and by 1969, he had helped Glamorgan to their first Championship since 1948. His batting was 'sheer magic,' his slip catching octopus-like, the valleys echoing his name. There, too, his legend was sealed.

The Melbourne Breakthrough and Flowing Test Success

Test success, for Majid, was not immediate; it arrived with the slow dignity of something destined, not rushed. Fourteen matches passed, and then, at Melbourne in 1973, he lifted himself into permanence with 158—an innings of velvet certainty, as if the bat itself had been tuned to harmony. From there, the runs flowed like a melody: twin 79s at Wellington, another hundred at Auckland, each phrase struck with cadence, not calculation.

Nottingham 1974: Pakistan's Historic One-Day Century Achievement

For Majid, batting was never attrition; it was a flourish, never grind. Even his failures had about them the fragrance of style, as though elegance were his natural condition, inseparable from him. Then came Nottingham, 1974. Pakistan's fourteenth one-day international, England's 245 thought safe and solid. But Majid's bat moved with the breeze of summer and made the score seem fragile, provisional. He flayed Bob Willis, John Lever, Derek Underwood, and Chris Old as though mocking the very presumption of "par." His 109, compiled from 93 balls, was Pakistan's first one-day century, a feat born not of aggression but of lyricism.

At a time when a run a ball was a heresy, Majid turned it into poetry. He was no hoarder of runs, no Javed Miandad with his fight, no Zaheer Abbas with his endless gathering. Majid belonged elsewhere, in a finer realm: an aesthete, an aristocrat, a player whose every stroke could hush a stadium, make cynicism kneel, and reveal beauty as the true measure of greatness. Majid Khan was never just a cricketer; he was cricket remembering itself—its own romantic soul whispered forward into a modern age.

The 1975 Sovereign Period of Masterful Batting

By 1975, he was sovereign of his art, his strokes taming the ball with the calm of a man soothing a wild creature. When the West Indies brought Andrew Roberts, Keith Boyce, Vanburn Holder, and Bernard Julien to Karachi, pace and guile entwined, Majid answered with a century spun of silk and certainty. A fortnight later, for Punjab A against Sind A, he made 213, as though the boundary rope existed only to mark the music of his bat. In those days he seemed less mortal than medium: cricket had borrowed his hands to remind the world of its beauty.

The 1975 Prudential World Cup and Greg Chappell Comparison

The Prudential World Cup of 1975 caught him in this imperious mood. Pakistan, brave and raw, came within a wicket of toppling Clive Lloyd's Caribbean giants, undone only by the harsh education of inexperience. Majid made 209 runs in three matches, twice standing as captain in Asif Iqbal's absence, his batting alive with that peculiar inevitability which was his signature. That summer, he made 110 for Glamorgan against the Australians, Greg Chappell replying with 144. Yet, as Huw Richards noted, even Chappell, captain, heir to Donald Bradman's order, seemed "prosaic by comparison." Such was Majid's gift: brilliance in others became muted when set against his ease.

The 1976 Glamorgan Finale and Karachi Century Masterpiece

His final summer with Glamorgan, in 1976, was a diminuendo, a softening of music before the stage was changed. But cricket often saves its richest notes for a shifted scene. When New Zealand came to Pakistan later that year, Majid turned incompleteness into permanence. In Karachi, October 1976, against Richard Hadlee, Richard Collinge, and Lance Cairns, he banished the nineties forever. By lunch on the opening day he had made 108 not out, the first since Bradman at Headingley in 1930 to reach a hundred before the interval. The crowd did not roar; it gasped, sensing it had seen not an innings but an apparition from cricket's golden age, returned in flesh and bat.

Caribbean Conquests Against the Most Formidable Fast Bowling Battery

And yet, the truest trial of his majesty lay far from home. In 1977, Pakistan crossed into the Caribbean to face the most formidable battery ever gathered—Roberts, Garner, Croft, Holder. There, amidst thunder, Majid stood tallest. He began with 88 at Barbados, then dogged runs in Trinidad, where every ball was peril. But in Guyana, he gave his masterpiece. With Pakistan adrift, Majid first turned bowler, claiming 4 for 45, and then turned redeemer, chiselling 167 in six hours of defiance and grace. Roberts struck Sadiq Mohammad on the jaw; Majid did not flinch. He hooked, he drove, he endured—composure incarnate, his elegance made armour.

From Lahore Maidans to International Cricket Stardom

He was Lahore's son, shaped on its maidans from 1961, and the plush grounds such as Aitchison College raised in the dust and glow of its afternoons, before stepping into Test whites against Australia in 1964–65 and then across seas to England in 1967.

At Swansea, against Glamorgan, he made 147 in 89 radiant minutes, Roger Davis suffering five sixes in one over. Wilf Wooller, Glamorgan's secretary and once a Cambridge companion of Dr Jahangir Khan, looked upon him and saw not only the son of an old friend, but a phenomenon newly born. By 1968 Glamorgan was his second home; the Welsh hills echoed to the music of his bat. In 1972, he won the Walter Lawrence Trophy with a hundred in seventy minutes, speed married to style. From 1973 to 1976, as captain, he made more than 9,000 runs and 21 centuries, weaving himself into Welsh folklore until he seemed, impossibly, a child of that land. The lineage was as rich as his strokeplay.

Opening Partnership Excellence and Gentleman's Cricket Ethics

For Pakistan, he began in the middle order, but in 1974, he was moved up to open with Sadiq Mohammad. There, against the shine of the new ball, his genius gleamed purest. That summer, he carved Pakistan's first one-day century—another jewel in his crown. In the slip,s he was peerless, converting the fiercest chances into gentle inevitabilities. And he was a "walker," upholding the fading etiquette of cricket, choosing honour over advantage even as the codes of the gentleman's game began to wither. Majid Khan was not only a batsman; he was the lingering music of cricket itself, its melody remembered in afternoons long past, its poetry written not in statistics but in the memory of eyes that saw him, and hearts that once quickened at his strokes.

Caribbean Apotheosis: 530 Runs Against Pace and Fury

His apotheosis came, as such things must, beneath the blinding light of the Caribbean sun in 1976–77. There, on islands where pace itself seemed to stride in elemental fury—Roberts, Holding, Garner, Croft in thunderous relay—Majid Khan did not so much resist as flower. Against the tempest, he fashioned 530 runs, and at Georgetown he left, as on a cathedral wall, his grandest fresco: 167 runs wrought with defiance and serenity, a second-innings psalm that rescued Pakistan from the certainty of ruin. The series was lost, but Majid emerged burnished, his name spoken with reverence even among those islands where fire and fury were thought the natural order of things.

The Patient Journey to Cricket Greatness and Artistic Excellence

Majid's progress to greatness had not been swift; cricket, like a jealous deity, chose to test his patience. For 14 Tests, he played the prologue, until at Melbourne in 1973 he raised his bat for 158—an innings that seemed less made than revealed, as though grace itself had bided its time.

Thereafter, the runs sang: twin 79s at Wellington, another hundred at Auckland. His was never the drudgery of survival. Batting, for Majid, was always a flourish, never a grind; even failure had about it the perfume of style, as if elegance were inseparable from his being. At Nottingham in 1974, in Pakistan's fourteenth one-day international, he turned prophecy into fact. England's 245 looked fortress enough until Majid came to dismantle its stones. Willis, Lever, Underwood, Old—all were reduced to the footnotes of his blade. His 109 from 93 balls—Pakistan's first one-day century—was no mechanical striking, but lyricism, a poem of bat upon ball. In that era, to score at a run a ball was heresy; Majid made it a hymn.

And still, he was never an accumulator of the accountant's sort. Miandad fought; Zaheer gathered; Majid adorned. He was the aesthete, the aristocrat of the crease, who made cricket appear less a contest than a festival of style. His inconsistencies themselves were forgiven, for in between, he gave innings that silenced entire stadiums, leaving beauty as their lingering truth. He was cricket's own memory, a romantic echo from its past carried into the modern day.

The Poetry of Fielding Excellence and Leadership Grace

He did not conquer the game so much as grace it. He was charmed, given form, an aesthete at play, an unbending man of nobility and candour. In him, cricket was not reduced to mechanics or statistics, but lifted into the atmosphere, into music. He belonged to that rare company of cricketers who left not merely runs but enchantment, who made the game shimmer with romance. Majid was—simply, profoundly—a joy to behold.

In the slips, Majid Khan seemed less a fielder than a poet of instinct; the ball, obedient to some unseen rhyme, found its way to his hands with the inevitability of verse. He gathered catches as though plucking ripe fruit from a summer orchard—without haste, without surprise, with only the serenity of expectation fulfilled. In Wales, as captain of Glamorgan, he wove himself into the legend of the valleys, until his name belonged as much to the hills and voices of the land as to the scorebooks. And in Pakistan's colours, when he took guard at the top of the order, bareheaded against Roberts, Holding, Garner, and Croft, he did not emerge battered, but burnished—his strokes cast back at them with the authority of calm. He seemed, in that theatre of menace, to take pleasure in the contest, as though the roar of speed and fury only deepened his composure.

Cricket's Eternal Aristocrat and the Definition of Majesty

Yet always there lingered about him a romantic fragility, the suggestion that he belonged less to the arithmetic of averages than to the fleeting realm of impression. He was not Miandad, the ceaseless fighter; nor Zaheer, the steady architect of accumulation. Majid was something rarer—he was majesty itself, his greatness measured not in the ledgers but in the memory of those who saw him. He was the cricketer who made you love cricket, not for the conquest but for the adornment, not for the tally but for the charm.

Majid Khan remains, and will remain, cricket's aristocrat—his speech as straight as his bat, his bearing regal without pretence, his honesty intractable as granite, his presence casting a radiance that gave the game a new shimmer. He was not just a batsman, but a silhouette upon the green stage, etched forever like a figure bathed in the declining light of an autumn afternoon. To see him was to know that cricket, in its truest form, is not the business of runs and reckonings, but the poetry of elegance embodied in a man who wore regality as naturally as breath.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has been the highest in ratings and acclaim.