Why Imtiaz Sipra remains Pakistan's most influential sports journalist 20 years later

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

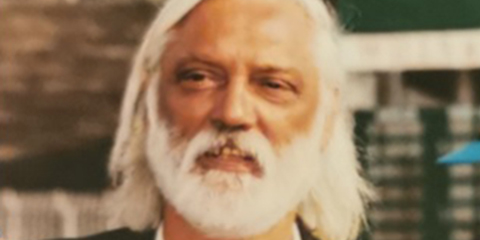

ISLAMABAD—His hair, white as ash yet restless in the faintest breeze, framed a face marked by a moustache of pure silver, streaked with a curious brown, the burnt legacy of a lifetime of smoking. Imtiaz Sipra carried the air of a man half consumed by his own fire, yet what he produced on the page was of another order altogether. He was not merely a writer; he was a phenomenon, a storm of words that left his readers both bewildered and entranced.

Early Life and Athletic Philosophy

Born in Rangoon in 1938, Sipra lived as though sport was not a pastime but a philosophy. He was not easy to understand, nor easy to approach, a man who seemed sculpted from a different order of thought. His sentences whirled with a poetic frenzy, his imagination soared beyond familiar tether, and those who followed his work found themselves hypnotised, swept along by currents they could not predict. He did not write for the casual eye; his audience was select, those who cherished Edwardian flourish, who could find humour in barbed satire and elegance in archaic expression.

The Complexity of Sipra's Writing Style

His writing was its own labyrinth, abstruse, shadowed, and obscure. In it lay theology, psychology, and the foreboding of prophecy, all wound together in a voice both mellow and dramatic. Few understood it fully, but those who did saw in Sipra a writer who dared to inhabit the dark, who embraced complexity not as a burden but as truth. To read him was less to follow a story than to be pulled into an atmosphere, an opaque, intoxicating mist where intellect and poetry met, and where, for a moment, the ordinary world fell away.

Behind the Public Persona: The Real Imtiaz Sipra

Sipra was a man steeped in wisdom, though the world around him often misread it. To many, he seemed abrasive, too quick to needle and annoy, a man without practical use. Yet for those who breathed cricket, who sought meaning beyond scoreboards and statistics, Sipra was of immeasurable value. His voice carried resonance, his words textured the game in ways no other could, sharp, poetic, and unafraid.

Much was said, and much misunderstood, about the man himself. Behind the veneer was a loving father, a teacher, and a figure of disarming honesty. Yes, he wrestled with alcohol and smoke, habits that dulled the brightness of his brilliance, yet these were but intrusions upon a far larger truth. When he was himself, without the haze, Sipra was an institution: a philosopher in press boxes, a raconteur among colleagues, his stories tumoring forth between overs, his mind entwining cricket into literature and satire.

### Government College Years: Shaping a Literary Voice

Sipra belonged first to the lanes of Lahore, to the sandstone arches of Government College, now Government University, where he was less a student than a force of nature. He hurdled the 110 metres with the fury of a man chasing liberation, sprinting not for medals but for release. That instinct for freedom marked him for life. He argued because he would not submit, contended because compromise was a prison. To watch him even then was to know: this was a man whose core was unshakable, whose fire would not dim.

Working at The News International: A Colleague's Perspective

I had the fortune of sharing rooms and press boxes with him at The News International. We wrote under the same masthead, though never from the same altitude. He was the mainstream, a star in his trade; I, the novice learning to string paragraphs into coherence. He was not the mentor you needed, because mentorship requires one to descend, and Sipra never descended. His intellect was pitched too high, his words cast too far; he soared in a sky that we could only glimpse. Yet, in his very distance lay the aura, the flamboyance that left you half dazzled, half unsettled.

Memorable Encounters: The West Indies Tour

I remember the West Indies tour most vividly. I hosted him once, a privilege I still recall with awe. He would sit, glass in hand, laughter in bursts, anecdotes spilling like coins from a pocket, and yet, you never knew him. He could reveal everything in a moment and remain opaque, a riddle wrapped in smoke. That was his genius, perhaps his tragedy too: Sipra dazzled not by what he explained, but by what he withheld. He was both light and shadow, flamboyant and elusive, and in his company, you were left struck not by understanding, but by the sheer impossibility of truly knowing him.

He lived extravagantly, as if life were too brief to ration, and his talents spread far beyond cricket, golf, polo, athletics, bridge, and boxing; all fell within his restless grasp. In July 2001, a cardiac arrest stilled him, and with it, one of the most enigmatic voices of sports writing in Pakistan. At the time, he was serving as Sports Editor of The News in Lahore. What remained after him was not just a career, but a legend, Sipra the brilliant, Sipra the flawed, Sipra who could turn the banal rhythms of a match into something interminable.

Revolutionary Approach to Cricket Writing

Sipra's approach to cricket writing was nothing short of alchemy. He took what had long been a ledger of facts, scores, overs, dismissals, and breathed into it colour, sensation, and criticism. What had been a flat record became a vivid description, and criticism turned into art. It is why his contemporaries, and those who followed, have never been able to escape his shadow; he is considered to have shaped every cricket writer who came after. Though his largest readership came through cricket, he himself held sports as his true vocation. Without formal training, he listened not with technique but with instinct, drawing early influence from Ashley Cooper and Neville Cardus. Yet he broke from their objectivity, carving a voice of his own, romantic, subjective, deeply personal. Sipra probed and dissected, leaned close to the chest of the cricket, and heard its heartbeat.

His judgments were sharp, his opinions forthright, sometimes bruising the egos of performers. But his charm, irrepressible, gregarious, disarmed resistance. He covered cricket and followed golf. He made friends across two worlds.They found in him not only a critic, but a companion who dignified their crafts with words that shimmered between irony and tenderness. His dignified cricket writing as Cardus had dignified history; he illuminated it, made it art.

And so his genius lay in refusal, refusal to be bound, refusal to choose. Sipra and cricket, fact and feeling, critique and poetry, all were fused in his sentences. He turned reportage into revelation. His was not the science of measurement, but the romance of sensation. To read him was to see cricket not as a pastime, but as theatre; music not as score, but as heartbeat. He gave both worlds their lyricist, their interpreter, their ally and in doing so, he proved that prose could make even the common games of men feel eternal.

Cricket as Literature: Sipra's Unique Style

Sipra did not just write about cricket; he reimagined how cricket could be written. Before him, cricket prose was largely a logbook, a record of runs, wickets, and weather. With him, the game acquired atmosphere, cadence, and mood. Sipra transformed the green oval into a stage where the players became characters in a novel, and the match a theatre of human temperament. He described not just what happened, but what it felt like to witness it. That was his gift, to render cricket as experience rather than event.

His sentences, long yet never languid, had the rhythm of frenzy and fire. Sipra's style was a storm, abstruse, dark, satirical drawing on psychology and philosophy, twisting cricket into metaphors that lingered long after the game was done. His instinct was always subjective, fiercely individual, alive to the unseen currents beneath the scoreboard. He had no hesitation in likening a batsman's stubbornness to a tragic hero's fate, or a bowler's persistence to the rumbling motif of destiny. It was prose that scorched with metaphor, that lingered on atmosphere, that found in cricket the very texture of life.

Comparing Literary Giants: Sipra vs. Cooper vs. Robertson-Glasgow

Ashley Cooper, by contrast, was a man of precision and polish, a stylist who prized clarity above flourish. His prose was beautifully crafted, but it obeyed the discipline of restraint. Cooper wrote cricket as a gentleman's game, his words dignified, even formal, as though he stood in a tie and blazer while the game unfolded. He was a master of balance, refusing to be swept away by sentiment. Where Sipra would describe a cover drive as though it were a shaft of lightning tearing through cloud, Cooper would note it with refined admiration, offering elegance without extravagance. His writing carried the authority of an educated observer, careful not to over-indulge, content to illuminate without dramatising.

Robertson-Glasgow, 'Crusoe, ' as he signed himself, was the opposite pole again. If Sipra was fire and philosophy, and Cooper was refinement, Glasgow was laughter tinged with melancholy. A cricketer himself, he wrote with the intimacy of one who had lived the game's fears and failures. His writing was less about grandeur and more about humanity: the comic absurdity of missed catches, the tragedy of a batsman's nerves, the quiet companionship of the pavilion. Glasgow's style was whimsical, self-deprecating, often playful, but beneath the humour ran a current of poignancy. He saw cricket not as theatre nor as polished art, but as a mirror of human fallibility. Where Sipra blazed, Glasgow softened.

To compare the three is to see the spectrum of cricket writing itself. Sipra elevated it into a strange, lyrical, almost prophetic literature, making it burn, making it sting, making it something greater than sport. Cooper maintained its dignity, its Englishness, writing with precision and polish, never straying into the extravagance of metaphor. Glasgow, meanwhile, turned it into an anecdote and parable, preserving its laughter and its quiet sadness. Together, they defined the golden age of cricket prose, one that was varied, colourful, and enduring.

And yet, it is Sipra who lingers longest, because he dared to treat cricket as if it were life itself. To him, the oval was not merely a field of play, but a landscape of memory, satire, and philosophy. His writing, lyrical and instinctive, convinced a generation that cricket could be more than a game. It could be literature. It could be darkness. It could be soul.

The Personal Cost of Genius

Sipra carried the dislocations of history within him. A migrant to Pakistan, his passion was not a pastime but an affliction, sport not a diversion but a field upon which he enacted his inner tumult. He did not write for the common palate. His sentences were Edwardian in weight, his satire sharp enough to draw blood, his metaphors belonging to an older world where literature still bowed to grandeur. He wrote for the few, not the many; for those who delighted in difficulty, who saw in darkness a kind of clarity. Among cricket writers, he was an aberration, too fiery to flatter, too uncompromising to be easily contained. And yet, those who dared to follow his prose found themselves entranced, unable to shake the spell of a mind that roamed through theology, psychology, and prophecy, and somehow still returned to cricket.

Sipra's life was as combustible as his style. He began smoking and drinking as though they were flirtations, teenage indulgences, only to be claimed by them later as companions for life. They dulled the gloss of his brilliance, but never erased it. Among colleagues, he was part philosopher, part trickster, always a storyteller whose anecdotes lit up press boxes and hotel lobbies. He could be abrasive, infuriating even, but beneath the bluster, there was a father who adored his daughters, a teacher who gave more than he took, a man who, when stripped of his vices, was an institution unto himself. His range was extravagant: golf, polo, boxing, athletics, nothing escaped his restless construct.

Final Years: Grief and Solitude

Imtiaz Sipra lived his final years as a loner, not by choice, but by the cruel reckoning of grief. When his wife, his anchor, his most tender refuge, passed away in 1999, a silence descended on him that even his words, so fierce and unrelenting on paper, could not pierce. He drank more, smoked more, and withdrew further into himself. The laughter that once scattered through press boxes became rarer, subdued, as though the man who once conjured fire in sentences had been dimmed by a loss too immense to bear. For a writer who saw cricket as life itself, the game too seemed to lose some of its colour, its capacity to console.

Legacy Through Family: Adnan and Umbreen Sipra

When Sipra finally fell, struck by cardiac arrest in July 2001, it was his children who stood by his side of memory. Adnan, his son, already a journalist, attempted to carry the torch of his father's style, abstruse, satirical, darkly lyrical. He wrote with courage, but the weight of Sipra's legacy was immense, too jagged to be shouldered consistently. Sipra's prose was not just technique; it was a philosophy, a storm born of temperament and torment, a rare alchemy that could not be reproduced in neat inheritance. Adnan followed the flame but knew, as all sons of great fathers do, that some fires cannot be relit, only remembered.

Umbreen, his daughter, idolised him as daughters often do, not for his words, but for the father behind them. To her, Sipra was not the satirist, not the storm, not the enigmatic figure who confounded peers and enthralled readers. He was the man she had adored, the man whose absence could not be consoled by pages or tributes. She still mourns him, quietly, faithfully, as if each day without him is another reminder that genius is often loneliest at home. If cricket lovers mourned Sipra the writer, Umbreen mourned Sipra the father. Her grief, unlike his prose, does not demand to be analysed. It is simpler, more enduring, and perhaps more profound.

The Enduring Impact of a Literary Pioneer

Sipra's legacy, then, is not just the essays and columns he left behind, nor the storms of language that scorched the scorecard into myth. It is the image of a man who, even in solitude, changed the way cricket could be felt. He took the game out of its ledgers and thrust it into the realm of literature, frenetic, unpredictable, alive. And in the quiet after his passing, in the mourning of his children, one sees the truth of Sipra's life: that beyond the satire, beyond the fire, beyond the endless smoke, there was love, and it was that love, as much as his words, that continues to echo.

When he died in 2001, serving still as Sports Editor of The News, Lahore, it was as though a peculiar star had burnt itself out. He left behind no school, no imitators, for his kind could not be copied. What Sipra gave was something rarer: the reminder that sports writing need not be plain, need not be servile. It could be unsettling, it could be lyrical, it could be philosophy dressed as play. In an age where commentary has become tamasha and writing reduced to scorecards, Sipra's ghost lingers as an admonition that cricket deserves more than mere record-keeping. It deserves fire, poetry, and madness. And in Sipra, for all his flaws, it had exactly that.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show Game On Hai has been the highest in ratings and acclaim.