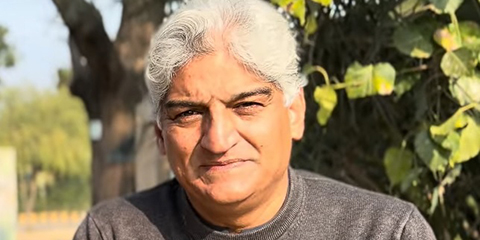

Usman Sherazi: The Pakistani journalist who exposed match-fixing scandals and became a global automotive entrepreneur

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

ISLAMABAD — I first came upon the name of Usman Sherazi not in a crowded newsroom, nor across the clink of tea cups in a press box, but through his bylines. They carried the weight of a craftsman's chisel, the authority of a voice that had already discovered its cadence.

His stories were not written; they were sculpted, unveiled, revealed with a flair that left the page humming long after one had folded the newspaper shut. He had that rare gift: to grill the mighty without fear, to expose the complacent with elegance, to take offenders to the cleaners with a prose that was at once suave and unflinching.

Rising Through the Ranks: A Self-Made Sports Journalist

Sherazi was no beneficiary of favours or indulgences. He was a child of the grind, rising through the ranks, winning bylines the hard way, earned, never bestowed. For a long while, I knew him only through indirect feedback, through the tales others told of his daring. How he had broken the story of the mutiny stirring against Wasim Akram before the ill-fated New Zealand tour in 1993-94. How he had placed the ringing call to Arif Ali Khan Abbasi that reverberated like a shot fired in the stillness. His dispatches from the West Indies of 1993, his vigils through the Australian tour of 1994–95, his fearless stance in the press room when Sarfraz Nawaz threw down his gauntlet of allegations at Karachi, all of these were spoken of as one might speak of a man who refused to just observe history, but insisted upon chiselling his name into its margins.

Professional Connections and Cricket Coverage Excellence

We would cross paths, fleetingly. A distant hello, the brush of a handshake, a nod in corridors that carried the smoke of rumour and the clatter of deadlines. I knew of his closeness to Aamir Sohail, and perhaps, because Aamir and I were often in each other's company, I felt that indirect kinship too. But kinship needs no introduction when language itself is blood. Sherazi's prose carried the savour of honesty, palatable yet piercing, a stream that ran distinct from the commonplace. His reporting was never perfunctory; it was abrasive where it must be, meticulous always, and spectacularly attentive to the detail that lesser correspondents would abandon to the margins.

Breaking the South Africa Match-Fixing Scandal

And then there was South Africa, that tour written in the folklore of rants, quarrels, and alleged conspiracies. Dressing-room doors rattled not just with anger but with the suspicion of darker games. In that maelstrom, Sherazi stood at the prow. He was among the very first to give voice to Rashid Latif's revelations, to string the unspoken into the public ear, and in doing so, placed himself at the vanguard of truth-telling when truth was most endangered. His work in those years was not reporting alone; it was a kind of crusade, catapulting him into fame not sought, but deserved.

A True Correspondent with Remarkable Character

To say he was a correspondent is to diminish him; he was a genuine one, in the oldest, hardest sense of the word, a warhorse of the press, a relentless pursuer of the story, a raconteur of both spectacle and shadow. And yet, behind the print and the grind, there resided a man of startling decency. When at last we truly connected, the sensation was not of meeting anew but of recognition, as though we had been companions in some earlier age.

The Regret of Losing a Journalism Giant

Usman Sherazi is a gem, that rare journalist who combined courage with compassion, tenacity with tenderness. And so I fret, I regret, that he turned his back on journalism's battlefield, choosing instead the quieter triumphs of Peru. He has done well, remarkably well. Yet for those of us who remain, there lingers the ache of an absence: a man of words and valour who, had he stayed, might have written the chronicles of an entire era in letters that endure.

Early Life and Educational Foundation

He was born in Alipur Syedan, Narowal District, a child destined, though neither he nor his kin knew it then, to dwell amid the print and cadence of the written word. The soil of Punjab gave him his roots, Lahore Cantonment its discipline, and the Forman Christian College its polish, English Literature, Economics, and Journalism pouring into him like tributaries feeding a restless river. Those years fashioned his mind into both scalpel and lyre: precise enough to dissect, lyrical enough to charm.

First Steps into Pakistani Journalism

It was in the first dawn of 1989 that he entered the clamour of the newsroom, that peculiar theatre where truth is sculpted daily and discarded nightly, where the smell of print is part incense, part blood. The Daily Mashriq took him in as a Sub Editor, and the press, always voracious, always demanding, received him as one might receive a tentative violinist into an orchestra: unsure of his notes, yet trembling with promise.

The Pivotal Mentorship of Zafar Samdani

Fate, ever whimsical, appeared to him in the form of Zafar Samdani, a man whose veins seemed laced with both cricket and prose. It was Samdani who, discerning beneath Sherazi's political leanings a fire that belonged to sport, nudged him toward the realm of games and contests, scoreboards and sagas. He placed the young aspirant under Imtiaz Sipra, a figure as flamboyant as Lahore's own twilight, and from that day Sherazi's path began to twine with the fortunes of sport.

Building the Frontier Post Sports Desk

Together they lit the lamps of the Sports Desk at the newly born Frontier Post in Lahore. That newsroom became to Sherazi both furnace and minster. Sipra was paradox incarnate: an open door to circles otherwise sealed, yet a presence too mercurial to be tethered to the desk. Out he would stride to golf tournaments sprawled across the country, to endless nights of bridge at the Gymkhana, to receptions where politics and sport intermingled like strong wine. And so it was upon Sherazi that the weight of deadlines descended, the nightly grind of producing pages that editors Samdani and Khaled Ahmed would scrutinise like hawks. No lapse escaped them; each misplaced comma was treated with the severity of a dropped catch in the slips. Under such eyes, the young man hardened. What for others took years of erosion, for him took mere months of pressure: he was transfigured into steel.

Developing a Distinctive Writing Style

Yet the steel was never devoid of rhythm. Headlines he crafted became small poems, rhymed, cadenced, bearing that curious trick of sounding inevitable once read. He had learnt it from Sipra, who began always with the title and let the piece gather around it, like a symphony swelling from a single motif.

The Workaholic Years and Dedication to Craft

The office lamps abided witness to his nights: long vigils that stretched to dawn, followed by mornings where he returned with eyes burning but pen still restless. His colleagues called him a 'workaholic,' but such terms are too banal for a man who had, without fully realising it, espoused himself to journalism with the fidelity of a monastic to his cloister.

Promotion to Sports Editor at 22

When Sipra left for The News in 1991, Sherazi was but twenty-two. Youth, however, is no barrier when responsibility falls heavily; he was raised then to Sports Editor. And he, far from cowering before the magnitude of the role, opened his arms to it as a cricketer might to a first cap, nervously, yes, but with pride radiant. Under his command, the Frontier Post became more than a paper; it was a mirror in which Lahore's sporting life recognised itself.

Revolutionary Local Sports Coverage

He gave attention not only to cricket and hockey, already enthroned in the nation's imagination but to the neglected disciplines: wrestling with its earthbound majesty, bodybuilding with its sculpted theatre, squash, athletics, football in the gullies. He walked the club grounds of Lahore himself, inhaling the dust where future talent blossomed unnoticed, ensuring his photographers caught the glimmers of those unnamed prodigies. His insistence on local sport coverage was unprecedented, and soon the Post was the daily scripture of the city's playing fields.

The Historic Imran Khan Interview

In the late 1980s, when the air of Lahore was thick with the dust of politics and cricket alike, a young man named Usman stepped tentatively into the world of journalism. His apprenticeship began at the Daily Mashriq, where his eyes were first turned towards politics. He dreamed of covering the elections, of walking in step with men such as Salman Taseer and Aitzaz Ahsan, whose campaigns in 1988 carried the restless promise of a changing Pakistan. Yet destiny, with its sly and unyielding hand, diverted his course.

It came in the form of Zafar Samdani, a gentleman of patrician grace, his English flowing with elegance. Samdani took the young aspirant from the hurly-burly of political journalism and gently, though firmly, ushered him into the unpredictable theatre of sport. Thus began Usman's first great passage, as Sports Editor of the newly launched Frontier Post in 1989, his youth crowned by the rare distinction of being elected the first President of the Lahore Sports Journalists Association.

Securing the Coveted Imran Khan Interview

At this very hour, Imran Khan, phoenix-like, had returned from retirement to bestride the international arena in his pomp. Usman, hungry for his first significant interview, sought the aid of Khalid Ahmad, Imran's cousin and himself a journalist of raw brilliance, clad often in torn shirts and jeans but bearing the polish of the most educated class. Another companion, Jawad Goraya, tall, handsome, the one who had won APNS Best Reporter awards twice, and President of the Lahore Press Club, drove them in his modest Suzuki to Zaman Park. For over two hours, they waited at the gates of Imran's residence before, at last, the great man appeared, and then, after yet another spell of silence, admitted them.

The Two-Hour Interview That Made Headlines

The interview stretched for two hours, two hours in which Usman encountered not only a cricketer, but the very embodiment of Pakistan's sporting conscience. The Frontier Post placed the piece upon its front page, adorned with a coloured photograph. By morning, it was the talk of Lahore. Usman, shyly approaching Imran at the stadium the next day, was staggered to find that every word had been read, and every editorial blemish noticed. Such was Imran: fastidious, unfooled, unbending. From that day forward, the young journalist knew he must write with care, for Imran demanded truth in every syllable.

Navigating Imran Khan's Complex Personality

Encouraged by the very man he admired, Usman grew bold. He wrote with aggression, and Imran, though never one to shrink from anger, accepted even the lash of criticism. Yet the mercurial temperament of the cricketer was not concealed. At Gaddafi Stadium one afternoon, while Usman and his colleagues Fareshteh Gati Aslam and Aliya Rasheed stood nearby, Imran emerged from the pavilion. A fan pressed too closely for an autograph. With sudden fury, Imran cursed and struck him. The silence that followed was cathedral-like, stunned, and echoing.

Witnessing Imran's Heroic Cricket Moments

But in contrast, there were other glimpses, softer, more human. Usman remembered Imran on a treacherous pitch, defying fate alongside the debutant Masood Anwar, batting through the day to save a Test match against an unsparing West Indies. Later, he quipped to Usman with boyish mischief, 'Where is Imtiaz Sipra? He will not believe we have saved the Test.' There was humour, pride, a warmth momentarily breaking through the armour.

The Desmond Haynes Controversy

Equally memorable was the episode when Usman interviewed Desmond Haynes, who accused Pakistan's bowlers of tampering and their umpires of cheating. When Usman relayed these words, Imran's retort came with volcanic indignation. 'No bowler of mine tampers,' he declared, 'and the West Indian umpires, why, they are the greatest cheats of all.' At the Frontier Post, the caricaturist Fiqa seized upon this tempest and drew a cartoon, Haynes presenting flowers, Imran striking a fan. Astonishingly, Imran took no offence. The storm, for once, passed him by.

Observing Imran's Transformation

Years later, Usman would contemplate a changed man. The Imran who had once been mercurial on the pitch now stood in the streets, drenched in sweat, collecting donations for the Shaukat Khanum Cancer Hospital. Crowds pressed about him, voices clamoured, yet he no longer struck back in anger. He endured the tumult with patience, the fire of his cricketing years tempered into the labour of service. Thus, in the memory of Usman, Imran Khan remains a paradox: volatile yet magnanimous, fierce yet capable of patience, a man of contradictions who demanded respect not by asking for it but by being the immovable centre of every room he entered. And for Usman, those early years, the first decade of journalism, were gilded by such encounters, the kind that turn the apprenticeship of youth into the vocation of a lifetime.

First Signs of Cricket Corruption in the West Indies

He had gone to cover the tours of South Africa and Zimbabwe for the Frontier Post. The rhythms of cricket consumed his days, though he himself did not travel to Zimbabwe. In South Africa, a call arrived from Peru, summoning him beyond the boundaries of the game. Chile and Peru beckoned, the visa secured in Cape Town, and he resolved then to leave journalism behind. The proposition was alluring, the integrity of his work unquestioned, yet already he was connecting dots, signs first glimpsed in the West Indies in 1993.

The Suspicious Ratan Mehta Encounter

He rejoined after the Grenada beach incident, arriving before the first Test in Trinidad. The Hilton became their lodging, and the following evening the West Indies Cricket Board hosted a reception. There he observed a figure who would become emblematic of shadowy undercurrents, Ratan Mehta, conspicuous in his presence, moving among players and administrators alike, a newlywed of twenty years' age at his side. Through Victor, a friend of Richie Richardson, Mehta passed easily into the company of the West Indies cricketers. He claimed to be honeymooning, yet his social reach was vast, and his proximity troubling. Clarity began to dawn.

The Mudassar Nazar Revelation

On the eve of the Antigua Test, Pakistan, already trailing 2–0, came an evening of strange consequence. He dined with Rameez Raja, Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis, and Mudassar Nazar at Victor's villa, perched precariously upon a cliff. Returning late, they entered the hotel elevator together. He departed on the fourth floor, Mudassar higher still. But Mudassar's tone lingered, strangely weighted, as he asked if sleep pressed upon him. 'I want to share something with you,' Mudassar said, and so he followed him to his room. There, in an atmosphere taut with disbelief, the revelation came, and that revelation Usman has reserved for Rashid Latif's autobiography, so he didn't spill the beans. Yet he knew this was no solitary shadow. Aamer would hint at dark possibilities but never speak them aloud. Whispers always drifted, like smoke without fire.

The Sarfraz Nawaz Allegations and Press Conference Drama

The Singer Trophy came and went without him; he was unconvinced but felt the tremors beneath the surface. Then in the winter of 1994–95, during the Test series against Australia, came the loud accusation. Sarfraz Nawaz alleged Pakistan's side was already 'in the books.' On the fourth day came a missed stumping, the air thick with suspicion. A press conference, hastily convened in Karachi, unfolded like theatre. The press, emboldened and hostile, circled around Salim Malik, who stood trembling beneath the glare. Intikhab Alam quivered beside him.

Defending Players Against Corruption Allegations

He, a Lahori, respected Malik, his friend, and never entertained the divisions of Karachi and Lahore. In his columns, he had promoted Sajid Ali, Saeed Azad, Arshad Khan, Mohammad Ramzan, and Ejaz Junior, always giving them prominence, six columns wide with photographs. Merit, not geography, was his measure. Even Salahuddin 'Sallu' Mulla, whom he often criticised, acknowledged his candour: 'You play on the front foot,' Sallu once told him. 'It is what it is,' he replied.

Confronting Cricket Board Officials

At the press conference, Malik was already condemned in the eyes of Karachi's press. Javed Miandad had been removed, and Malik shouldered the mantle of villain. He interjected, diverting the barrage with questions of cricket, not innuendo, desperate to steer discourse towards the game itself. Yet the currents were already raging. In fury, he confronted Arif Ali Khan Abbasi, then CEO, flanked by Asad Mustafa and Subhan Ahmad. 'Chief,' he demanded, 'do you think your players are corrupt? Why not stand by them?' Abbasi, eloquent and commanding, declared the PCB's faith in its team, dismissing Sarfraz as a man without credibility.

Exposing PCB Financial Corruption

But consequences followed. Pakistan lost the triangular, the Singer Trophy slipping away. Aamer Sohail, injured, returned to Lahore with a concussion, yet struck a century. Malik, meanwhile, soared in extraordinary form. He himself turned his pen towards another angle, exposing how the PCB squandered money on the series, contracts flowing to friends of officials. Dr. Zafar Altaf and Javed Burki receded into the shadows while Abbasi ruled unchecked. The critique earned him disfavour. Mustafa Khan, the austere Secretary, offered him no courtesy. At the PCB, he was marked persona non grata; his accreditation for South Africa manoeuvred with difficulty.

The South Africa Tour and Political Encounters

In Johannesburg, for the Nicky Oppenheimer match, 40 kilometres from the city, he asked Intikhab Alam for a lift. Intikhab declined. So he hired a taxi, as apartheid's legacy still lingered in the air. At the venue, he met Dr. Ali Bacher, whose visits to Pakistan had left behind a history of warm exchanges. Chris Day, the media manager, labelled them 'heavyweights of the Pakistani press' and urged silence against complaints. They met Frederik Willem de Klerk, who was once the president before Mandela, now his vice president. From that day, we were treated like royalty.

Dr. Ali Bacher, with the air of a man who felt slighted by destiny itself, lamented the manner in which the Ad Hoc Committee of the PCB had seen fit to treat him during his sojourn. To his mind, courtesy had been mislaid, hospitality reduced to mere convenience. At Rawalpindi, where one might have expected a table laid with linen and the ceremonious dignity due to honoured guests, the luncheon was presented in humble cardboard boxes, soft to the touch, indifferent to grace. It was, in his view, not merely a meal diminished but a symbol of neglect, an affront to the old courtesies by which visiting dignitaries had long been acknowledged. For cricket, after all, had never been only about the game upon the field; it was a theatre of manners, a stage upon which respect was rehearsed and performed. And to serve repast in boxes was, to his sensibility, to forget that truth.

The East London Incident with Aamer Sohail

In Johannesburg, Pakistan fell to South Africa and then travelled to East London to face New Zealand. On the flight, he noticed Aamer was strangely quiet, unusually subdued, and asleep for the 90 minutes. In East London, they stayed at the Holiday Inn, Rashid Latif in one room, himself in another, Aamer and Saeed sharing theirs. Aamer's CD player, borrowed and carried, found its way into his room.

Salim Malik's Mysterious Promise

As practice beckoned, he prepared the curtain raiser. Interviewing Malik, he asked if changes were expected. Malik's smile, peculiar, mischievous, lingered in his memory: 'We'll give you a surprise.' 'In batting?' he pressed. Malik, inscrutable, hinted but refused to clarify. With Aamer in form, Saeed Anwar scoring, Ijaz and Basit solid, Malik himself the one failing, who could the sacrifice be? He wrote it in the curtain raiser nonetheless.

Witnessing Team Internal Conflicts

That evening came a knock. Aamer demanded his CD player. Conversation unfolded, the puzzle exposed: 'It will be me,' Aamer confided, his face reddening, abusive in his agitation. Soon the phone rang. Rashid, the vice-captain on tour, had summoned him, asking for Aamer. Rashid resisted, unwilling to surrender himself. Aamer stormed in fury, crying betrayal. 'They intend to send me back,' he shouted. 'How can they? I will go myself.'

And so he witnessed the fissures within, the betrayals half-hidden, half-revealed, fragments of a game haunted by shadows, where the pride of Pakistan met the corruption of whispers, and where one man, steadfast, refused to barter conscience for coin.

International Cricket Coverage and Match-Fixing Crusade

The world widened before him. He covered England 1992, West Indies 1993, South Africa 1994-95. Typhoid denied him New Zealand, but even illness could not still his voice. In 1998, when Pakistan and India met in Toronto for the Sahara Cup, he flew in from New York to bear witness, the press box once more his pulpit. But journalism is not just spectacle; it is a crusade. In 1996, when the World Cup came home to the subcontinent, Sherazi felt anew the calling. Match-fixing's foul odour had begun to seep into cricket's sanctum, and he, almost alone at first, dared to chronicle it. Later, others would join, but Sherazi was among the vanguard: it was he who first set down Rashid Latif's revelations, he who held fast when officialdom preferred silence. For him, the press was not a pastime; it was a battlefield, and the truth was worth wounds.

Transition to International Business

His energy was restless, irrepressible. In 1995, he had already ventured to South America, drawn by family ties and opportunity. Peru and Chile became his stage, automobiles his trade, Spanish his new tongue, learnt swiftly, worn with ease. Yet the world of sport pulled him back, like an old melody that haunts even when unheard. By 1996, he returned to join Sipra again at The News, Lahore, now with greater circulation, greater reach.

Leaving Journalism for Business Ventures

But journalism in Pakistan was not an arena that rewarded courage. The more he wrote, the more he saw the indifference of those in power to address corruption gnawing at cricket's soul. Discontent grew in him, like a stone in the shoe of a long-distance runner. Having tasted life abroad, he weighed his options. Eventually, he departed, before the electronic media explosion of General Musharraf's era, to fashion a different life. In Canada, he carved out new empires. By 2002, he was building on eight acres: a truck stop that was part enterprise, part monument, gas station, store, restaurant, all conjured from his restless industry. Later, he returned once more to Peru, to the automobile trade, to dealing vehicles under 15 brands. His life became a shuttle between Canada and South America, each continent another newsroom, but of commerce rather than newsprint.

Once a Journalist, Always a Journalist

And yet, Beena Sarwar, his colleague of earlier days, once spoke the phrase that fits him still: 'once a journalist, always a journalist.' For though Sherazi may sell cars in Lima or supervise land in Toronto, beneath the surface the print yet runs in his blood. The instinct to observe, to interrogate, to set words into cadence, it remains.

A Mohican of the Press

He is, in truth, a Mohican of the press: one of the last of that generation who believed journalism was a craft, not a commodity; a calling, not a career. He walked away, yes, but with the walk of a man who has already given enough to be remembered. His pages are still there, the revelations, the exposés, the match reports that caught the tremor beneath the statistics. He may live now in contentment across hemispheres, but for those who knew his bylines, his vigils, his prose, the newsroom lamp still glows with his presence.

The Enduring Legacy

And so the story of Usman Sherazi is not of a journalist lost, but of one transfigured: a man who carried the fervour of Lahore's dusty grounds into continents far away, and who even now, should he lift a laptop and write, would remind us that journalism, like cricket itself, is at its best not only about records and numbers, but about the music of human character, the courage to face the pitch, the grace to write as if the game were literature.

Biography as Allegory of a Calling

Sherazi's journey is not only the biography of a man but the allegory of a calling. Journalism claimed him young, taught him to compress the infinite into headlines, to turn the day's chaos into legible order. Sport gave him its fragrance, dust of Lahore, drizzle of London, sunlight of Barbados. Illness attempted to arrest him; commerce tried to absorb him. Yet through each incarnation, there remained that indelible sense of vocation: to observe, to shape, to chronicle.

The Spirit That Endures

One imagines him today, having abandoned his venture, selling out the Canadian truck business, still the negotiations of a Peruvian dealership, and somewhere within his breast, the faint applause of an old pavilion in Lahore still resounds. The ink stains may have long faded from his fingers, yet the spirit of the page lingers in his veins. He is of that rare species who carry not professions but destinies.

And perhaps that is the final, unspoken headline of Sherazi's story: 'Man of Many Callings, Servant of One Spirit.' For beneath the shifts of place and profession, he remains what Sipra first taught him to be, a craftsman of resonance, a man whose every undertaking, whether headline or truck stop, was written in that same terse, rhymed, and resonant key.

Brotherhood of the Press

For all his detours across continents, Sherazi belongs indelibly to that brotherhood of the press, an order now dwindling, perhaps already half-forgotten, a breed of craftsmen for whom journalism was never merely a trade but a creed. In the quiet of his later years, as commerce piles its ledgers upon his desk, there come, unbidden, recollections of earlier vigils. He remembers the midnight newsroom, its lamps burning like tired watchmen, its walls echoing with the percussion of typewriter keys. Outside, Lahore would sink into the hushed hours, but inside, the paper throbbed with urgency, words hammered into permanence before dawn demanded its copies. It was a place half sacred, half chaotic, where deadlines cracked whips and inspiration flared suddenly like struck matches. Sherazi was young then, with eyes fevered by ambition, yet already he approached journalism less as an occupation than as a covenant.

The Sacred Nature of Journalism

To him, the newspaper was not parchment for casual scribbles; it was scripture. Every headline was a psalm to be composed with precision, every report an act of witness. And so the paradox remains: Sherazi, the merchant, the builder, the dealer of vehicles, yet always and eternally Sherazi, the journalist. In exile, he has become emblematic of a breed now passing into memory, those for whom journalism was less a career than a covenant. He may sit at a desk covered in invoices, yet in the silence between transactions, there lingers the ghostly chorus of his past: the clatter of typewriters, the murmurs before presses roll, the fellowship of colleagues long dispersed.

The Eternal Spirit of the Word

The temples may crumble, the presses may fall silent, but their bells ring still within him. In every silence, one may almost hear the rhythm of a headline waiting to be struck, the rustle of a report longing to be filed. And thus Sherazi stands, not just as a man of many callings, but as a servant of one enduring spirit—the spirit of the word, undying, unconquered, eternal.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has been the highest in ratings and acclaim.