The tragic story of Wasim Raja: Cricket's charismatic genius who died playing the game he loved

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

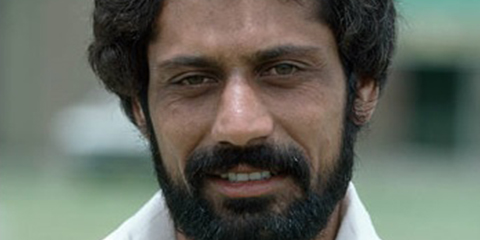

ISLAMABAD — Wasim Raja, born on July 3, 1952, was less a cricketer and more a statement of style. A left-hander of languid grace, a leg-spinner of deceptive guile, he belonged to that rare fraternity who did not just play the game but seemed to converse with it, absorb its pressures, and return them in strokes laced with poise. He is remembered not by numbers alone, but by the manner in which he carried himself on the field, with elegance, with defiance, with an artistry that belonged more to lyricism than to scorecards.

The Cricket Dynasty: From Sargodha to International Stardom

He came from a family steeped in the folklore of cricket. His father, Raja Saleem Akhtar, had once captained Sargodha, a first-class cricketer who later turned to the rigours of civil service. His brothers, too, Rameez and Zaeem, would play representative cricket, with Rameez rising even to the captaincy of Pakistan. But it was Wasim, the eldest, who first set the tone, the boy who blended inheritance with individuality, who brought to the game not just a surname but a sensibility.

Scholar-Athlete: Balancing Cricket and Academics

What made Raja singular was his balance between the mind and the body, the crease and the classroom. He made his first-class debut at 15, still a boy, yet already drenched in cricket's flow. Later, at Punjab University, he pursued a Master's in Politics, graduating with distinction. Few men could glide between the cut shot and constitutional theory, between the forward defensive and the dialectic of governance, but Wasim could. Cricket was his craft; learning was his anchor.

Master of Fast Bowling: The West Indies Specialist

And yet, it was against the West Indies that storm of fast men, that empire of intimidation that Raja carved his finest chapters. His Test career often fluttered in and out, inconsistency tugging at his promise, but against the world's best, his game soared to improbable heights. His numbers tell a tale: 919 runs in 11 Tests against the West Indies, an average of 57.44, a maiden hundred in Karachi in 1975. But the numbers, though shimmering, only hint at the romance. For it was not just that he scored runs; it was how he did it with strokes that cut through pace as if dismissing fear itself, with a regal calm that mocked the fury hurled at him.

The Edgbaston Masterclass: World Cup 1975 Heroics

Then came Edgbaston, the World Cup of 1975. Pakistan versus West Indies. The stage was urgent, the air taut with possibility. Pakistan were 140 for three when Raja walked in. Others faltered before the fire, but for him, it was as if the contest was personal. His 58 off 57 balls, a strike rate beyond its time, was played with authority, every stroke laced with clarity, every run a rebellion. Pakistan reached 266, enough to dream of victory. And though the West Indies escaped, saved by the improbable defiance of Murray and Roberts, Raja had already written his arrival. His innings was not only about runs; it was about audacity, about showing that grace could exist even in the furnace of Caribbean pace.

The Artist's Inconsistency: Brilliance in Adversity

Wasim Raja's career was one of tantalising glimpses of brilliance that often came draped in inconsistency, but when he shone, he did so like few others could. His cricket was not a method; it was a mood. Not a science; a sonnet. He remains remembered not as a figure in Pakistan's history, but as a man who played cricket as though it were an art form, fleeting, delicate, regal.

Caribbean Conquest: The 1976-77 Series Masterpiece

To say Wasim Raja loved playing the West Indies would be an understatement bordering on insult. They were, after all, the strongest side of their era, an empire of fast bowlers, an orchestra of intimidation. Few cricketers found themselves, truly found themselves, against that storm. Raja was one. In the 1976–77 series in the West Indies, he stood tall where others bent, scoring 517 runs in five Tests at an average of 57.44. Five fifties and a hundred flowed from his bat, each stroke carved with defiance. He was not just a batsman then, but an answer to their fury. And yet he gave more: seven wickets at an average of 18.71, leg-spin as wily as his batting was languid. Though Pakistan lost the series, the victory at Trinidad was etched in no small part by him. A fighting 70 in the second innings, three West Indian wickets on the final day, Raja did not just play the match; he inhabited it, carried it in that elegant, unhurried way that was his signature.

Politics and Rebellion: The Price of Integrity

But Raja's battles were not only against fast bowlers. At home, he clashed with the politics of Pakistani cricket, a labyrinth of bureaucracy and favour. He was too unbending, too regal in bearing to bend before men in offices. And so he was overlooked, pushed aside, his career clipped not by lack of talent but by refusal to yield. There is a story, half anecdote, half parable that he lost the chance to captain Pakistan because he once refused to hang out a senior's socks to dry. It sounds absurd, but in its absurdity lies the truth: Raja was never made to serve. He was made to stand.

Life After Cricket: From Referee to Teacher

Later, he found another calling as an ICC match referee between 2002 and 2004. There, too, his authority was evident, his understanding of cricket's spirit unquestionable. He officiated 15 Tests and 34 ODIs, lending the game the same dignity he once lent the cover drive. Life carried him elsewhere. He settled in England, marrying Anne, an Englishwoman, and built a quieter life of teaching. Together, they had two sons, Ali and Ahmad. It was, in its own way, a continuation of his elegance, taking the wanderer's path, yet carrying himself with the poise of a man who had lived fully in the game's heart.

A Hero's Death: Final Moments on the Field

And then, as if scripted by some cruel cosmic poet, he died as he lived on a cricket field. On August 23, 2006, in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, while playing for the Surrey over-50s side, he felt dizzy while fielding. Moments later, he collapsed, never to rise again. He was 54. The news stunned the cricket world. Obituaries flowed from all corners, each one less a formal notice than a lament. Wasim Raja was not simply a cricketer. He was a style, a mood, a way of playing that made even the hardest days look easy, that lent even defiance the air of grace.

The Cult Hero: Cross-Border Admiration

He left too soon. But then, perhaps, men who carry such peculiar regality are always destined to leave too soon. Standing tall in the crowded ensemble of Pakistan cricket was Wasim Raja — a figure oblivious to the tyranny of numbers, yet always summoned by the moment when it mattered most. He was a master of adversity, poetry in motion, a svelte teenage hero whose cult following has rarely been equalled, let alone surpassed.

The early 1980s burned with the fever of India–Pakistan rivalry, and by the late 1980s and 1990s it had swelled into theatre, politics and sport entwined. Amidst the frenzy, a few names crossed the hostile border and won affection even on the Indian side of Wagah. Among them, Wasim Raja, exuberant and untamed. Alongside Wasim Bari, his name was entwined even into the layout of popular cinema, immortalised in a line from Namak Halaal, proof that his persona was not confined to the boundary ropes alone.

The Genius of Elegance: Style Over Statistics

The word outstanding is worn thin these days, dulled into meaninglessness. It would not have escaped Raja's disdain. For he was, in the truest sense, outstanding. He batted with panache and a kind of lazy elegance, a dominance so natural it seemed unconscious. Against opposition of any calibre, he flourished, yet it was in adversity that his genius fully revealed itself. When the odds were cruel, he soared; when the game went easy, he sometimes drifted out, as if interest had deserted him.

If Javed Miandad was the insatiable street-fighter, if Zaheer Abbas was the stately run-machine, then Wasim Raja was the languid genius, the flâneur of batting, a man who seemed capable of anything, who made the most difficult look disarmingly simple. He often tired of the ease with which he mastered pace; legend has it he would bat at nets against the tearaway Imran Khan without pads, almost daring the game to offer him a challenge worthy of his artistry. Even Imran conceded, with a fast bowler's reluctant admiration, that Raja was 'in a different class altogether, already batting with a maturity beyond his years.'

The Art of Cricket: Poetry in Motion

Perhaps he was too talented for the mechanical labour of run-gathering, too regal to treat accumulation as toil. For him, batting was never war. It was a stroll in the park, a moody glance across a riverside café, a fleeting improvisation that dissolved into beauty. The loose, low stance, the impossibly high back-lift, the magical hand–eye coordination, the whip-like wrists, all of it irresistibly attractive, all of it a style unto itself.

There were times when he seemed almost absent, feet still, shoulders drooping, eyes dulled by ennui until, in the instant of release, everything came alive. Those languid eyes lit with sudden fire, those listless feet sprang into lightning motion, and in a heartbeat the ball was carved to the rope or lofted effortlessly over it. It was cricket as theatre, as illusion, as poetry carried in the wrists of a man who made even defiance look like grace.

Personal Memories: The Human Side of a Legend

I first encountered Wasim Raja in Faisalabad, 1979–80, where Pakistan played Australia on the dust and intimacy of Iqbal Stadium. There were no proper dressing rooms, so the players, stripped of theatre, sat in the VIP enclosures, their ordinariness brushing shoulders with the crowd. My father, then a Brigadier, later a Lieutenant General, held authority in the city, but I was just a boy of ten, chaperoned, holding the trembling pages of an autograph book.

There he was sitting beside Mudassar Nazar, light-hearted, laughter weaving between them like an unbroken thread of camaraderie. I took my book timidly; he signed, a gentle nod, a caress upon my hair. Later, when I brought him a slam book, he beckoned me back after an hour. In it, under favourite music band, he had written: Mudassar and The Animals. There was laughter all around, the joke a simple thing, but in it was his essence: playful, irreverent, weaving delight from the ordinary.

As the years stretched, so did my gaze upon him. By the late 1980s, I was playing in Rawalpindi's leagues, part of the Rawalpindi Division Cricket Association. Wasim was there too, still in the realm of first-class cricket. It was there our acquaintance grew into familiarity. One afternoon at Rawalpindi Club Ground, I sat just across the boundary ropes, absorbed in Jean-Paul Sartre. He was fielding in the deep. As the ball came to him, he threw it back, but not before plucking the book from my hand. Later, he asked if he might borrow it. I parted with it gladly. A year later, true to his conscientiousness, he returned it, signed, an act so small, yet immense in its fidelity.

The Eccentric Genius: Whimsical Yet Profound

He was eccentric, yes, delightfully so. Naeem Taj, now a surgeon of repute, once recalled a match where Wasim, in the first innings, shouldered arms and was bowled, leaving spectators bemused. He left the ground not in torment, but in appetite, wandering to Regal to savour samosa chaat. Yet, in the second innings, with National Bank tottering, he sculpted a hundred of rare beauty and turned the match on its head. That was Wasim Raja: whimsical yet profound, capable of frivolity one moment and transcendence the next.

He was a truthfulness rare in men, rarer still in cricketers. He was open about flaws, unguarded about virtues. Straight-faced, short-tempered at times, but always generous, always elegant, in cricket as in life. For me, he became a mentor of sorts, though the meetings were sporadic. In England, he would guide me, encourage my habits of collection, and promise me his first Pakistan blazer. For months, nothing came. Then a call: Wasim himself, asking for my address. Days later, a parcel arrived, the blazer folded within.

That was Wasim Raja. Eccentric yet regal, playful yet profound, unpolished in moments but never graceless. A man whose batsmanship was high on poise, whose life carried the same delicate, delectable elegance. A man who seemed, even in ordinary gestures, to remind you that beauty did not need perfection—it only needed truth.

The Charismatic Star: Hollywood Looks on the Cricket Field

When the willowy frame descended the pavilion steps and crossed into the green, he might have been mistaken for a leading man from a Hollywood reel. 'Doc, the buttons were always undone, collars defiantly raised, sleeves rolled to the elbow, the stride a swagger, and the beard or sometimes just the moustache, whatever whim struck me was less a style than a declaration. I did not dress for the occasion; I dressed for myself. If cricket were theatre, I walked on as its reluctant star.'

There was charisma baked into his very gait. Imran may have had the steel and the statesman's grandeur, but Wasim Raja he had the cinema in him. Gideon Haigh once said, 'Wasim Hasan Raja truly was a raja,' and perhaps he was right. I lived as if royalty did not need crowns.' His admirers spanned generations. Wasim Akram himself remembered the teenager who went to stadiums just to watch Raja. 'I was never followed only for the runs or the sixes, Doc. Crowds loved me, as I humbly contemplate, because I gave them abandon, a certain recklessness with elegance. I was not just playing; I was living a part of their own dreams on the field. That is why the boys of the 70s and 80s called me an idol.' It was not arrogance; it was an explicit explanation of what was seen and felt.

All-Round Excellence: More Than Just Batting Brilliance

But Raja was more than the flourish of a bat. 'I prided myself as much on my fielding as anything else. At cover or cover-point, I was a panther more than a cricketer—fleet-footed, sharp-eyed, restless. I wanted to remind the game that it could be won as much by grace in the field as by grandeur with the bat. And yes, I bowled too, leg breaks mostly, sometimes medium pace, even opened the bowling for Pakistan. But the truth? The board's politics, its pettiness, clipped my wings. Fifty-seven Tests and fifty-four ODIs, they barely sketch the outline of what could have been.'

He pauses, almost amused, when asked about numbers. 'The numbers, Nauman. Cold, stiff, unforgiving. They will never flatter me. Two thousand eight hundred and twenty-one Test runs at 36.00, just four hundreds, fifty-one wickets at 35, they call that ordinary. But then, in contrast, I was never built for the ordinary. I was the one, regardless of the numbers wanted to feel alive. The West Indies fast bowlers, the Australian hostility, that was my canvas. Against lesser storms, I was bored. Against tempests, I was counter-reacting. I must not defend this attitude, it was contrary to the professionalism required, still I believe, I wasn't cut for ambling without challenge.'

In first-class cricket too, the ledger seems austere: 11,434 runs at 35.00, though the ball spun sweeter from his hands, 558 wickets at 29.00, with 31 five-fors and 7 ten-fors. 'Perhaps, Nauman, my legacy is not in numbers at all. My cricket was mood, cadence, a gesture. The lift of a backlift, the lazy whip of wrists, the refusal to be ordinary. I was less a statistic and more a style. And maybe, just maybe, that is why they still remember me.'

Understanding the Numbers: Statistics That Tell A Story

'Nauman, numbers are skeletal things,' Raja began, his voice both careless and careful, as if numbers themselves were beneath him yet worth bending to his narrative. 'They tell you I played 57 Tests, that I scored 2,821 runs at 36.00. But the numbers don't tell you when the veins of the game throbbed, when the storm came alive, who stood and who bent. They don't tell you that against the West Indies, the very fury of cricket's age, I averaged 57.44.'

It was between 1976 and 1981, in the furnace of Anderson Roberts, Michael Holding, Joel Garner, Colin Croft, and later Malcolm Marshall, that Raja's legend was forged. 'Nauman, it was an era when cricket was not just competition, it was survival. Men came at you like avalanches, thunder in white flannels. Most prayed for mercy; I asked for the ball to be bowled faster.' His smile, half-wicked, half-philosophical, told you he meant it.

Against the West Indies, Raja scored 919 runs in 11 Tests, two centuries, five half-centuries, a ledger drenched not in accumulation but in defiance. Against everyone else, his average fell to 30.68. 'Do you see it, Doc? I did not care for the easy afternoons, for gentle bowling on flat decks. My blood only rose when the storm darkened I only picked up my sling when to the toughest walked in.'

'I was never meant to pile runs like a machine. I was meant to strike when others flinched, to prove that elegance could also be rebellion. Numbers flatter some; for me, they only delineated what my wrists already declared.' In those years of West Indian tyranny, Raja was not just a batsman. He was resistance clothed in elegance, poetry framed in peril. His numbers, against the greatest attack of all, remain a monument not to consistency, but to that peculiar regality which makes memory last longer than averages.

The West Indies Crucible: Where Legends Were Forged

'Nauman, you ask me of the lion's den,' Raja smiled, eyes narrowing as though remembering the crack of leather on concrete pitches, the echo of fearsome footsteps. 'Few men dared, fewer survived, and fewer still left with dignity intact. Yet there, in the West Indies, I enjoyed thoroughly.'

The numbers reveal their truth. Five Tests, 517 runs, an average of 57.44, a century gilded in heat, in hostility. Among the pantheon of those who walked into the West Indian storm, Steve Waugh, Mohinder Amarnath, Allan Border—Raja stands shoulder to shoulder. 'The fast bowlers were not just cricketers. They were weather systems. Roberts was thunder, Holding the wind, Garner the unscalable mountain, Croft pure menace, and then Marshall, he was the hurricane. Against them, runs were not accumulated. They were stolen, snatched, created from the thin air of defiance.'

Yet Raja was never a grafter. His runs were scored with the abandon of a painter's brush, strokes of flair carved against fury. 'I was not built to grind, Doc. My joy was in the audacity. Every pull, every flick, every lofted drive was rebellion against fear, against inevitability. I wanted to prove that beauty could survive even in fire.'

The Early Years: From Boy Wonder to Test Star

But Raja's story did not begin there, in the West Indies amphitheatres. It began much earlier, born of lineage. 'At fifteen, I made my first-class debut. By nineteen, I was playing Tests. I was a boy given a man's responsibility. And perhaps that's why, Nauman, I always played as if time was short, as if every innings had to be a flash of lightning.'

At Punjab University, where he studied political science, Raja scored a maiden century of 151 and followed it with seven wickets. All-round brilliance already visible. 'There were days when I felt cricket was just a canvas for moods. Some days I painted with runs, some days with wickets. Against Rawalpindi, I struck 80 and 57, and then with the Public Works Department, I picked ten wickets and a century in the same match. Those were the days that told me I could do anything, bat, bowl, or both, if I only dared.'

When the selectors sent him to New Zealand, he returned with quiet promise: 43 not out, nine wickets for 85 against Northern Districts, and then the Test debut at Wellington. 'Ten and 41 with the bat, a few wickets, nothing memorable. But then at Auckland, when I took three in the last innings, I began to believe my place was real. That's how a boy grows into his shirt, Nauman, not in glory, but in small triumphs.'

And then, Lord's, 1974. A rain-soaked pitch, baked dry into a graveyard for batsmen. Derek Underwood spun carnage from mud and clay. 'Pakistan collapsed, but I—walking in at 91 for three, faced him with defiance. I struck 24 from 38 balls, stroked four boundaries, until Tony Greig pulled off a miracle catch. It was not much in numbers, but in spirit, it told me I could handle the very best. That is how my life was measured. Not by tallies, not by averages, but by moments when the world thought collapse was certain, and I insisted on beauty instead.'

Memorable Innings: Defining Moments of a Career

'I remember England in those days.' Raja began, his voice carrying the weight of memory. 'Underwood was not just a bowler; he was damp earth turned into a weapon. In the second innings at Lord's, Pakistan staggered at 77 for three when I walked in. For once, I was dour, leaving aside my careless flourish. I played 142 balls for a hard-earned 53, called by Wisden a 'masterly display'. With Mushtaq, I added 115, but rain was always the accomplice of fate. Once I fell, Pakistan folded from 192 for four to 226, undone again by Underwood's sorcery. Yet, in that collapse, England realised, and so did we, that I could withstand their deadliest.'

'My true baptism came not against England, but against the West Indies,' he smiled, a trace of pride glinting. 'They had conquered India, and they came to Karachi with fire. First Majid Khan lit the air with a hundred, and then I, at 170 for four, carried the torch. The crowd poured onto the field, policemen clearing space around me. It was a spectacle, a drama. And though later I tore a ligament and hobbled in at eleven only to be undone by Lance Gibbs, that hundred had already announced me.'

'You ask of Edgbaston, the World Cup, 1975? Ah, that was colour in a grey English summer. West Indies, Anderson Roberts breathing fire, Majid batting with grace but unable to escape their chokehold. I walked in at 140 for three. Suddenly, Nauman, the fast bowlers looked human. I danced down, I cut, I drove—fifty-eight from fifty-seven balls, each stroke loosening the noose. With Mushtaq, I ran like a boy possessed, turning ones into twos, unsettling the giants. We reached 266, enough, almost. Sarfraz had them 166 for eight, but Derryck Murray and Roberts stole it away. Still, that innings became my offering to one-day cricket: a brief rebellion that made giants look mortal.'

The Caribbean Chronicles: Epic Battles in the West Indies

Then his voice softened, reverent. 'But if you seek my finest hour, it is written in the West Indies of 1976–77. Against Roberts, Holding, Garner, Croft—the most merciless attack ever assembled—I scored 517 runs at 57.44 and claimed seven wickets at 18.71. They say John R. Reid is the only other man to have done such a thing.' He did it with my usual air of nonchalance. Rob Steen wrote that he never looked like he cared for numbers—perhaps that made it more extraordinary.

He paused, and his eyes glowed. 'At Kensington Oval, I came in at 207 for five. I was supposed to perish. Instead, I left on 117 not out, batting 260 minutes, twelve fours, one six, and giving Pakistan parity. Next innings, when we were 158 for nine, Bari and I added 133, my 71 defiant, my strokes, honestly, well-thought-out. West Indies were tired of me by then, tired of this thorn in their side.'

'At Queen's Park Oval, Colin Croft destroyed us, eight for twenty-nine, and Pakistan crumbled for 180. But even in ruins, I tried standing, scoring 65 with ease, turning rubble into resistance. That was my way, not to amass but to counterattack, to carve runs out of fire. You must understand—by the time West Indies had secured their lead, I had already decided I would not surrender,' Raja said, leaning back as if replaying the strokes in his mind. 'They kept making inroads, but again I rose. That 84, in 180 minutes, with seven fours and two sixes, was not just an innings; it was defiance dressed in elegance. Four consecutive innings I had top-scored; the West Indian fire would not consume me easily. West Indies chased their 205, yes, but I had already cracked their opening stand, and Croft, for all his menace, had to share the Man of the Match with me.'

'At Bourda I failed, but the Oval brought me back,' his tone sharpened. 'They call it Mushtaq's Test—for he struck 121 and 56, and with ball conjured 5 for 28 and 3 for 69. But, Nauman, I played my part. In the second innings, I made 70, a quick-fire burst with six fours and three sixes, to set West Indies an impossible chase. Later, I finished it with 3 for 22.' That was him—runs and wickets, rebellion and theatre. At Sabina Park, the script thickened. 'They were 182 without loss, looking like destiny itself. Then, with ball in hand, I dismissed Roy Fredericks, Vivian Richards, Clive Lloyd—all names that hung over cricket like myth. I ended with 3 for 65. When they set us 442, we were 138 for five. That was when Asif and I did the repair works—115 runs in 95 minutes. I made 64, and when I fell, so did Pakistan. But even in defeat, it was beauty that endured.'

The Power Game: A Master of the Big Hit

Majid Khan had said Raja could 'hit a six when he liked.' Raja laughed. 'Majid was not often left gaping, but yes, I could. Liking and the penchant to clear the fence were the essence. That series I struck fourteen sixes, more than any man in Test history for a single contest.' Later years softened his smile. 'India, 1979–80—I scored 450 runs at 56, five fifties, two nineties. Only Javed (Miandad) stood anywhere near me. Against West Indies again in 1980–81, I posted 246 runs at 61.00. They could dismiss me just four times all series. But then came the fade, fleeting sparks, Jullundur, where I made 125, then 4 for 50. The body tired, the form fell. By New Zealand 1984–85, it was over. I was thirty-two. My final act, a domestic flourish of 129 with wickets to match, and then a quiet exit.'

He paused, eyes glinting with memory and mischief. 'They call it a career, Nauman. I call it a rebellion—batting darned into defiance, a life lived on my own terms. I was never meant for numbers. I was meant for moments.'

The Final Chapter: Cricket Administration and Tragedy

Raja began, his voice half-resigned, half-proud. 'I was never one to bend before bureaucracy or bow to the age-old hierarchies that strangled Pakistan cricket. Politics marred the game, and I clashed with the board more often than I care to recall.'

'They overlooked me, though everyone knew I thrived when the skies were darkest and the conditions most cruel. That captaincy, the post so coveted, always eluded me. They say it was over socks, Nauman. Socks! I refused to dry a senior's pair, and so I was marked forever as unfit for command. Better that than bend.' He smiled faintly, almost wryly. 'I walked away when I must. I even resigned as coach in 1999 rather than be shackled to their whims. England welcomed me.'

And then, the ICC—for a while, Raja huddled with the blazer of the referee, 15 Tests, 34 ODIs between 2002 and 2004. But destiny had a crueler script. At Marlow, in 2006, fielding for Surrey's Over-50s, the heart gave in. On the green fields he loved, he fell. And cricket wept. Obituaries poured in from every corner. Even Javed Miandad, parsimonious in praise, could not hold back. 'We grew together, played together—as mates and foes. He was a true sportsman, a thorough gentleman, and I've stood with him in some of the finest matches of my life. To lose him is to lose an ambassador of this country.'

The Golden Era: Among Pakistan's Greatest

The era was drenched with luminaries: Imran Khan, Miandad, with his dagger hidden in silk; Mushtaq, fox-eyed and cunning; Majid Khan, effervescent, as if born to the crease; Sarfraz Nawaz mercurial; Was Bari efficient; Intikhab Alam wise. And then there was Wasim Raja. The man who lived not in numbers but in moments. He was poetry in motion when the storm raged. A svelte teenager in appearance, but a cult in defiance. His career average reads under 37.00, yes. But against the West Indies, those monsters of fast bowling, he averaged nearly sixty. It was a rarity in cricket, but it was his. He thrived where others wilted.

He was never a grafter. He was rebellion made flesh. His stance was never textbook, his shots never obedient. High backlift, supple wrists, uncanny eye, that was his orthodoxy. They called him a rebel, and perhaps he was. But what was cricket, if not rebellion against inevitability? He let the silence sit. Then, with the faint trace of a smile. He didn't have Zaheer Abbas' grace or Javed Miandad's ruthlessness, Majid Khan's reality, or Asif Iqbal's guile. But he was when the pitch was treacherous and the bowlers snarling, he could stand with them all.

Legacy Beyond Numbers: The Eternal Rebel

There are cricketers who are measured by their averages, their centuries, their wickets, and their monuments in numbers. And then there was Wasim Hassan Raja — who slipped through the grasp of numbers like smoke through fingers. His cricket was not a ledger to be tallied, it was a lyric to be read aloud, a brushstroke across a canvas, brief yet indelible. In a game obsessed with grit, Raja's resilience wore a mask of nonchalance.

He was regal without trying, princely without inheritance. He strolled to the crease with shirt unbuttoned, collar up, beard or moustache of the day in place, as if auditioning for a part in a film whose script he alone understood. The crowd adored him not simply for what he did, but for what he was — the embodiment of effortless charisma. Children imitated the lift of his bat, teenagers saw in him a mirror of rebellion, and poets found in him a metaphor for grace under fire. Raja's story, like all true cricketing stories, was shadowed by the politics of his era. He refused to hang out a senior's socks and lost the Pakistan captaincy hopes. He clashed with administrators, challenged hierarchies, and lived too freely for the bureaucratic order of the board. Perhaps that is why he played only 57 Tests when he might have played a hundred. Yet perhaps that is also why he remains unforgotten, for there was something gloriously untamed about him, something that numbers could never box.

After cricket, he became a teacher in England, a quiet geography master who had once conquered Roberts and Marshall, a schoolhouse sage who had once lit stadiums with fire. It seemed improbable that such flamboyance could find a home in classrooms, but Raja wore it with the same shrug as everything else. His final bow came not in ceremony, but in cricket itself: collapsing while playing for Surrey's over-50s, still fielding, still running, still part of the game that had both defined and devoured him. Wasim Raja was many things — batsman, bowler, fielder, brother, teacher. But more than all of them, he was lyricism. He belonged to the rare class of cricketers who played not to win alone, but to remind us that beauty was its own form of victory.

He left behind his wife, Anne, his sons Ali and Ahmad, and a nation's memory of a man who looked every inch a prince and batted every ball as though he had been born for that fleeting, eternal moment. In an era of numbers, Wasim Hassan Raja will be remembered for everything numbers cannot hold: elegance, courage, rebellion, and that peculiar princely grace that still glimmers, and it will perpetually.

In an era of numbers, Wasim Hassan Raja will be remembered for everything numbers cannot hold: elegance, courage, rebellion, and that peculiar princely grace that still glimmers, and it will perpetually.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has been the highest in ratings and acclaim.