How one man saved Pakistan's early cricket history: The Qamaruddin Butt story

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

ISLAMABAD—There are names in cricket journalism that do not shout, only work quietly. They don't dominate panel shows or fire off viral tweets. They don't write with the scathing-sharp edge of critique, nor do they drown in metaphors. Instead, they persist—page after page, tour after tour—building something sturdier than spectacle: a record. In the history of Pakistani cricket writing, Butt was that kind of name.

He wrote not in prose but as functionally as a government memo, his sentences draped in the grey of bureaucratic correctness. There was no seduction in his syntax, no flash in his phrasing. His columns would not make the poets blush. His paragraphs carried no thunder, only the steady drizzle of fact. But to reduce Butt to his style is to miss the quiet lyricism of his presence.

He was the first to gather Pakistan cricket's tender, breakable memories, holding them as if in cupped hands, lest they be carried away like dust upon an evening breeze. Between 1954 and 1971, while the country itself was still uncertain of its own shape, Qamaruddin Butt set down ten slim books—stubborn volumes, produced out of his own means and sheer persistence—anchored in his belief that words could build permanence. They were never bestsellers, hardly known beyond a small circle. Now his name lingers only in the muted exchanges of book collectors, like incense curling in forgotten rooms. That is a sadness. For Butt not only understood cricket, he wrote of it with a voice wholly his own: odd, stubborn, wayward at times, but unmistakably lived. He deserves remembrance, not obscurity.

Early Life and Playing Career: From Amritsar to First-Class Cricket

The fragments of his life are sparse. Born in Amritsar in 1914, his photographs reveal a frame pared down, lean and angular, stripped of any excess. He played the game too, though fleetingly—seven first-class matches scattered across the disruptions of war and Partition. A determined right-hand batsman, a leg-break bowler. With a touch of mischief, he once claimed he had been a fast bowler. The record insists otherwise: a highest of 59, an average of twenty, wickets at thirty apiece. Modest, but with the quiet dignity of a man who had felt the ball in his hand, who had known the contest. On occasion, he kept wicket too—safe, reliable, unremarked.

From Player to Umpire: Standing Guard Over Cricket History

Another chapter of his life unfolded in the umpire's coat: fifty-three matches across two decades, and a single Test in 1964 at Rawalpindi—the only one that ground has ever seen. There is poetry in that fact: Butt, who sought permanence through words, standing watch over a match itself preserved in amber, solitary in the ground's history.

The Ministry Years and Cricket's Calling (1947-1962)

His career followed the nation's own beginnings: service in the Ministry of Interior, Karachi, from 1947 to 1962. Then, freed of files and forms, he gave himself wholly to cricket: to coaching perhaps, but chiefly to writing. His books were his livelihood, his devotion. Odd little things—meandering in part, sharp in flashes, never uniform. Yet in them lay the folklore of Pakistan's first cricketing years, rescued from the indifference that might have erased them. Without Butt, much of that story might have slipped away, unnamed, unrecorded. He was more than a writer; he was the archivist of beginnings, pressing permanence into frail triumphs and inevitable defeats alike.

'Pakistan on Cricket Map' (1954): The First Voice

His first voice came in 1954 with Pakistan on the Cricket Map. A curious book, one of four attempts to capture that first pilgrimage to England. Three were stitched together from press cuttings and wireless reports in Karachi or Lahore. Only Kardar's had the immediacy of presence, the damp grass underfoot, the drizzle on the face. Kardar had already written of Pakistan's first steps into India two years earlier. One suspects that without Fazal Mahmood's spell at The Oval, without the victory conjured in that summer's fading light, Butt's book may never have found paper at all.

Yet it did. And with it began his long vigil. He did not write for acclaim, nor for reward, but because he must—because without him, those tender, tentative years of Pakistan cricket would have slipped into silence. His prose was uneven, his humour dry and crooked, his style eccentric. But in those small volumes lay the first preservation of memory. He was poetry not in polish, but in devotion. In remembering, he lent permanence. In writing, he saved what would otherwise have been lost.

The book carried his own name as publisher, though in truth the state lingered behind the curtain, its presence betrayed in the roll-call of an eleven-man Advisory Board. Five of them stared stiffly from the opening leaves, their faces embalmed in Butt's peculiar flourish: "indefatigable and resourceful." And in the margins of those pages flickered the ghosts of corporate patronage: Burma-Shell Oil, a Saddar jeweller, a Karachi cycle shop — all snatching their slice of immortality in print, their advertisements set among Pakistan's fragile cricketing scripture.

Butt began with eccentricity, the sort that would become his hallmark. "If the cricketers of the dear dead days beyond recall were to be brought back to life, they will indeed be stunned to know something incredible, that it is now possible to listen to a ball-to-ball commentary." The sentence bent like a crooked grin, his voice less chronicler than conjuror, summoning cricket not as dry record but as theatre on the edge of the impossible. He claimed past writings, though no trace of them survives outside whatever lies entombed in state files. What does survive is a letter from Jack Hobbs, August 1954, weeks before the Oval's miracle, in which the old master wrote to Butt with startling prescience: Pakistan, he said, looked capable of defeating England in England. Perhaps even Hobbs could not have imagined how swiftly prophecy would harden into fact.

The book itself was a patchwork quilt: clipped reports, lifted scorecards, English newspaper extracts, stitched together with Butt's own longer essays — especially on The Oval, where he lingered lovingly, as though unwilling to let the miracle fade. He closed with tour averages, player sketches, and the bones of a record. Rough, unpolished, yet defiantly worthy: a first attempt that planted its flag against forgetfulness.

Building the Archive: 'Cricket Without Challenge' and Early Works

By the second book, Cricket Without Challenge, order had crept in. Maliksons of Sialkot and Lahore carried it to print, adorned with forty-four advertisers. This time Butt tracked India's visit in 1954–55. He confessed his purpose openly: that reports dissolve into the ether unless bound, unless given permanence. Posterity was his obsession. The Tests — five dreary stalemates — earned Wisden's rebuke for their "safety-first dullness." Butt, more severe, called them farce, and lanced Kardar himself. Deliciously, it was Kardar who wrote the foreword, laying blame only at India's door. Here, for the first time, Butt wrote as a man who had seen rather than heard. The structure was familiar, but his witness lent it weight: three guest essays, sketches even of Indian players, perhaps to soften the market. Yet sales faltered, and his third book, Pakistan Cricket on the March, returned to the shelter of private printing, Interior Ministry once more a shadowed hand.

This one stretched wider: New Zealand's 1955–56 visit, an England "A" side, then the Australians for that lone Karachi Test. That match he adored most — Pakistan felling Lindsay Hassett's men on a matting wicket, Fazal and Khan Mohammad pulling strings like puppet-masters.

The Caribbean Journey and West Indies Chronicles

In 1958, he sailed with the team to the Caribbean, a three-month leave from the Ministry to trail their fortunes. Cricket Wonders emerged — a modest paperback, again scattered with advertisements, privately done. Pakistan lost, Kardar's reign ended, but Butt's account endured, loyal to his small Karachi printer, his bureaucratic patrons.

The following year, he recorded the West Indies' return visit. Pakistan won 2–1, but Butt cut mercilessly: their batting, he said, was nothing but a crawl. Yet he softened unexpectedly in an appended elegy to Collie Smith, the young West Indian who dazzled that series and then perished tragically in an English crash. Butt, usually acerbic, wrote with tenderness, his pen momentarily shaken.

Through these early volumes, one can glimpse the shaping of him. Never a polished historian, nor always a consistent reporter. But a man whose books were stitched with advertisements and forewords, embroidered too with his idiosyncrasies, his irritations, his fierce individuality. They belonged to another rhythm of time — an age that could wait. His Cricket Cat and Mouse did not appear with the immediacy of headlines, but a year late, embalming the 3–0 mauling by Australia in slim paperback. Sharp-tongued, he lashed Pakistan's bowlers as feeble, but still, in the ruins, he found a flicker of promise in the final Test, as though at last his countrymen had begun to grasp what it meant to duel with Australians.

'Playing for a Draw' (1962): A Chronicle of Frustration

The delay, as ever, was not without its reasons. Butt by now was less a bureaucrat than a chronicler, and he had crossed the Wagah border to trail Pakistan's 1960–61 journey into India. What he saw was not so much cricket as a kind of arrested motion: five Tests, five stalemates, and every tour match the same—bat and ball shackled in a joyless embrace. It was not play, it was paralysis in flannels. And so he christened his chronicle with bitter honesty: Playing for a Draw. The title itself was sigh and snarl in one, dripping with his exasperation.

The introduction read like fury held on a leash. He declared that both sides were content to watch matches limp to their deaths. "It is no use apportioning blame," he wrote, before betraying himself, confessing that it made his blood boil to see sides so cowed by the spectre of defeat that they dared not even glance towards victory. Three hundred pages of stalemated prose followed—his bulkiest work, self-published once more, emerging in October 1962. By then, Butt had walked away from the Ministry of Interior, unshackling himself to tie his life fully to cricket's shifting fortunes.

That same year, England toured Pakistan, but strangely Butt did not capture those three Tests in covers. Nor did he travel to England later in 1962 when Pakistan crumbled so meekly. Silence stretched nearly three years, until 1964, when Cricket Reborn surfaced: a slender ninety-three-page paperback chronicling Pakistan's jousts with a Commonwealth XI of formidable constellation—Rohan Kanhai, Tom Graveney, Seymour Nurse, Basil Butcher, Basil D'Oliveira. The names were galaxies, but the matches fell into familiar inertia, weakened bowling dissolving contests into draws.

The book was unremarkable, a continuation of his template. Yet, tucked inside, a list of his earlier works—each still "available," save for the elusive Pakistan on Cricket Map and Cricket Wonders. It was permanence mocked by its own absence, two of his children already lost to time.

The 1967 England Tour and 'The Oval Memories'

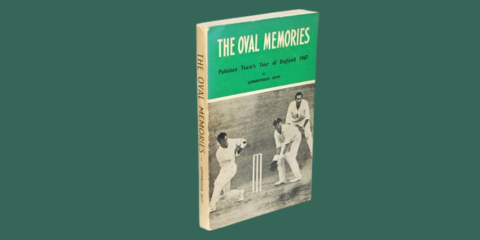

Perhaps ill through those years, Butt returned restored by 1967, when he became the first Pakistani journalist dispatched with a touring party to England. By then, his name was inked not only into mastheads of four dailies but also into Wisden and Playfair Cricket Monthly. Twice, even, he held the BBC microphone. From this pilgrimage sprang his bulkiest book of all: The Oval Memories.

The title clung to one luminous act in an otherwise bleak summer. At The Oval, in the third Test, Pakistan, battered and humiliated, staring into the abyss, found in Asif Iqbal and Intikhab Alam a defiance that shimmered like resurrection. From 65 for 8 they carved 190 for the ninth wicket, the clang of their bats briefly drowning inevitability. The match was still lost, but on that afternoon, a shred of pride was salvaged, and Butt, always drawn to the defiance of moments over the verdict of results, enshrined it forever.

Elsewhere, his metaphors held the texture of Lahore's melancholy streets. After one rain-wounded pitch left batsmen stumbling, he likened their efforts to "a dirty carburettor sputtering on a frosty morning." Not merely cricket, but theatre, but poetry in the ruins.

Final Years and 'Sporting Wickets' (1970): A Lasting Legacy

The years rolled by, and the country's air thickened with unrest. By February 1969, after the D'Oliveira Affair had rerouted itineraries, New Zealanders were hurried to Karachi. Pakistan was combustible, dissent thick in the streets. Two Tests wandered into a dull stalemate, the third disintegrated into chaos as riots spilled from roads to stands. That cricket returned within six months was remarkable. The New Zealanders came again; they won 1–0, the cricket itself uneventful, but Butt's response anything but.

In May 1970, he brought forth Sporting Wickets. His last, his longest, his most polished meditation. Within it, the tale of both New Zealand series, and a tender farewell to Hanif Mohammad—the little master's waning light stretching across Pakistan cricket like dusk across a city. Perhaps it was his finest work: sharper, more deliberate, shaded with rare personal affection.

By then, Butt was his own small industry. As ever, advertisements littered the pages. But already Cricket Cat and Mouse and Pakistan Cricket on the March were gone, sold out, lost to the collector's chase. Time, that ruthless archivist, has only inflated their value. Today, even his most modest paperbacks fetch close to a hundred pounds; a hardback with its jacket intact can summon more.

Death and Enduring Impact: The Collector's Chase

And then silence. No more books came. On 8 June 1974, at sixty, Butt collapsed from a heart attack while cycling home from a match. A cruel end for a man who had bound his very life to the rhythm of the scorebook. He was underrated then, and remains so now. But apart from rare exceptions, his are the only substantial records of those tours, the only attempt to pin permanence to contests otherwise dissolved.

John Arlott, with his customary kindness, noticed him in Wisden. Rowland Bowen, mercurial in Cricket Quarterly, reviewed only Playing for a Draw, complaining of tardiness, lamenting the lack of a Pakistani annual. Yet beneath the brusque eccentricity, there was a flicker of respect. Butt never chased the limelight. He chased cricket. Its beauty, its frailties, its brief ecstasies. His books endure not as monuments to grand triumphs alone, but as a record of cricket's lived texture—of the afternoons that might have vanished but for his stubborn pen.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show Game On Hai has been the highest in ratings and acclaim.