Cricket legend Wesley Hall: 'Fire in my bowling arm, kindness in my heart' — full interview

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

On Meeting Cricket's Legends

There are rare moments in a life when the clamour of the world subsides, when the noise of days collapses into silence, and you find yourself standing in a hush so profound that it feels almost sacred. It is the hush of reverence, the kind that steals over you when you come face to face with figures whose shadows have long preceded them, whose names echo not only as records but as incantations, carrying the weight of entire generations. To meet them is not to shake a hand or exchange pleasantries. It is to brush against history itself, to feel its pulse on your skin.

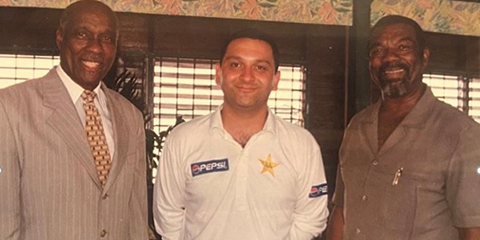

I remember such a moment as though it were yesterday, the day I stood before Wesley Hall, with Roy Gilchrist at his side. I first met him in 2000 and then again in 2014. The sight alone was disarming. Here were not men, not just cricketers, but storms personified. They belonged to an age when West Indian fast bowling was not a craft but a fury, when the ball hurled down at you was less a delivery than a philosophy: that domination was not optional, it was ordained.

Wesley Hall towered, not just in frame but in presence. To call him a bowler was to flatten him, to reduce the cathedral into stone. He was something more elemental: tall, upright, as though the sky itself had chosen him as the channel for its thunder. His run-up, impossibly long, once a ritual of dread for batsmen, was now only memory, but even in stillness he carried that echo. And yet, when he spoke, when he smiled, it was disarming, warmth where there had once been carnage. His was the aura of a man who had inhabited greatness but not surrendered to it, a man who had survived the furnace without being charred.

Beside him, Roy Gilchrist was cut from another cloth. Where Hall was stately, Gilchrist was restless; where Hall commanded, Gilchrist attacked. If Hall was basilica, Gilchrist was stormcloud; if Hall's greatness lay in majesty, Gilchrist's lived in fire. To see them together was to glimpse fast bowling's two souls: one sculpted, dignified, eternal; the other wild, furious, incandescent.

What struck me most was not their records, nor their stature, though both were immense. It was the folding of time. To stand there was to stand in two eras at once, mine, the present, and theirs, still vivid, still alive. Their stories spilled out not as myths retold, but as lived memories. Montages of wickets, of journeys, of victories, of exile, no longer confined to paper or broadcast, but spoken, felt, and laughed over in the immediacy of conversation.

And there were others, too. Encounters with men I had known only as names on scorecards or sepia-tinted images, men whose exploits I had pursued with the awe of a disciple. Each meeting carried its own reverence. Sometimes it was in the jolt of recognition, the almost childlike wonder of seeing a face that had once been only myth. Sometimes it was in the ordinariness — the realisation that even titans worry, eat, joke, grow frail. That even those who once conquered cricket's stage remain, in the end, only human.

But that is the lesson these meetings etch upon you: that greatness lies not in numbers or cold statistics. It lives in the residue they leave on generations — in the way their names summon not digits, but feelings: fear, awe, inspiration, longing. When you stand in their company, you do not stand with men alone. You stand with symbols, with emblems of a game that has lent your life shape, texture, and rhythm.

To meet Wesley Hall was to come face to face with the majesty of cricket itself, to see what grandeur looked like when distilled into human form. To stand beside Roy Gilchrist was to feel the pulse of cricket's wild, untamed heart. And in that hush, in that moment when time folded, when history stretched out its hand, I learnt that reverence is never an act you perform. It is something that grips you, unbidden, when greatness itself stands before you and asks nothing but to be seen.

On His Early Life and Cricket Development

Wes Hall was born on 12 September 1937, and from the very beginning, his life seemed destined to unfold in epic registers. He was more than a cricketer: first the hurricane fast bowler, then selector, manager, Board President, even a minister of both politics and the pulpit. His arc was not just of wickets and runs, but of faith and public service. And recently, when he was knighted, he became only the second genuine bowler in cricket's long history to receive such a crown, as though the game itself had risen to salute him.

He bowled, they said, with pace like fire. That became the title of his autobiography, though no phrase could contain the phenomenon. For he came thundering from a run-up that seemed endless, galloping like an Olympian long-jumper, six feet three of taut sinew gathering speed. His eyes bulged, his teeth flashed, and always, that crucifix swung forward with him, cutting the air as if it too were straining for release. At the crease, there came the leap, arms flailing like a cartwheel, and then the ball left his hand, vituperative and aflame, searing down the pitch at ninety miles an hour.

It was not imagination when batsmen thought he carried with him a streak of fire. CLR James, in the way only James could, wrote: 'Hall merely puts his head down and lets you have it, and it's pretty hot.; It was heat in every sense: not just speed, but the burning vitality of a man who bowled with his entire being. With Roy Gilchrist first, and later Charlie Griffith, he formed the earliest prototypes of the West Indies fast bowlers that would later dominate the 1970s and 80s. To watch him was unforgettable. Clayton Goodwin captured it best: 'The picture of Wesley Hall in full flow, as he ran towards the wicket, is still treasured in the memories of all but the opposing batsman and maybe in theirs as well.'

Yet what made Hall different, almost paradoxical, was his heart. Fearsome in action, tender in essence. Ted Dexter, who often felt the full thud of his thunderbolts, insisted: 'There was never a hint of malice in him or in his bowling.' When Wally Grout's jaw was shattered by one of his lifters, no one grieved more deeply than Hall himself. He could terrify batsmen, yes, but never intended to diminish them. He had more than just raw pace. In the subcontinent, he revealed another art—swing and subtle movement, the craftsman behind the storm. After dismantling India on debut in 1958–59, he came to Pakistan and inscribed his name in the record books: the first West Indian bowler to take a Test hat-trick, a feat befitting the legend he was fast becoming.

Wes Hall was not merely a bowler. He was spectacle, fire, faith, charisma, and compassion. His long run-up stretched further than the boundary ropes, it seemed—it stretched across decades, across roles, until at last it brought him to knighthood.

On the Historic Brisbane Tie and Lord's Marathon

'Doc,' Wesley adjusted himself on the cushion with that booming laugh which always seemed to echo across the room before it filled the heart, 'you talk of my knighthood as though it were a crown laid upon me at the end. But my name—my soul—was etched half a century earlier, in the sweat and fire of two Tests that will live forever.'

He would begin with Brisbane, 1960–61, where history itself turned a page. 'That last day, I ran in seventeen times, each run-up as long as a sermon, each over as full as a psalm. And still, when the hour was closing, I bowled again. One final over, eight balls of destiny. Three wickets tumbled, two run-outs burned like sparks, and then, the tie. The first in Test cricket. They said I had bowled till I emptied myself, and it was true. But it was the game that filled me back again.'

And then his eyes would soften, as though recalling a hymn sung long ago. 'Lord's, 1963. I overslept that morning, can you believe it, Doc? and Frank Worrell, that gentle prophet of the game, fed me two hard-boiled eggs. Only two! Yet I bowled for 200 minutes straight. Forty overs on the trot, four for ninety-three, and at the end only six runs between England and victory, one wicket between us and heartbreak. Sustained willpower? Perhaps. Adrenaline? Surely. But mostly it was the rhythm of life itself, pounding through my veins, one ball after another.'

Then, as if caught in confession, he would add: 'But that same day, I was undone by Brian Close. Imagine it, Doc, this small man walking down the pitch into my fire. And I stopped. Froze. Not out of fear for myself but for him. I did not want to hurt him. There I was, six foot three, quick as the gale, and yet suddenly, helpless, confused. I walked to Frank. I sank to my knees. He lifted me with words only he could conjure, sent me back to the mark, reminded me who I was. That day I learned that even fire can hesitate when it loves too much.'

The voice was slow, the pitch mellow. 'You see, Doctor, I was never just a bowler. I was a man who wanted to give joy. Johnnie Moyes called me box office. CLR James, bless him, said I exuded good nature through every pore. I'll take that. To be remembered not for wickets but for kindness, that is a true record.'

He shook his head at the memories of the years. 'The wear and tear came, of course. Fast bowling breaks the body, as surely as the sea wears down the cliff. I limped away in 1969, 192 wickets in the bag, my one first class hundred at Fenners tucked into my heart. And, Doc, I always said, it was not just any hundred. It was against the intelligentsia.' And then that grin, irrepressible: 'After cricket? I made speeches as long as my run-up. Joined politics. Minister of Tourism and Sports, they called me. I thought I was just the Minister of People. Then came the Board Presidency, the selector's hat, the manager's duty. I gave myself to the game, the country, the Caribbean. Cricket was my church, politics my pulpit.'

Finally, with a pause, as if letting the weight of time rest between his words:

'Doc, they knighted me. But the truth? My real accolade was always the laughter I left behind, the handshakes, the memories of fire without malice. The wickets will fade in the ledgers. But the man? He lives in those who still smile when they say, 'Wes Hall.'

On His Faith and Ministry

'Doc,' Wesley Hall, his voice carrying both the rumble of thunder and the softness of prayer, exclaimed, 'in 1990, I turned to a dimension no run-up could take me, no spell could measure. I made, as I tell it, a very serious decision to give heart and life to God. Cricket had taken me to fame, politics to power, but faith, faith gave me rest. I walked into Bible school not as a fast bowler or a minister of sport, but as a pilgrim, searching. And there, step by step, verse by verse, I was ordained a servant in the Pentecostal Church. My run-up to the crease had always been long; this was longer, but it led me to eternity.'

Then the laughter would fade, replaced by the tremor of memory. 'I carried the word of God not just to congregations, Doc, but into the room of my dear Malcolm. Malcolm Marshall, younger brother in the fire of fast bowling, lay dying of cancer, and I sat by his side. I was not the bowler then. I was the minister. I read him scripture, I prayed over him, I tried to steady his soul as he had steadied mine so many times. That partnership, Doc, not of wickets or runs, but of sorrow and faith was the hardest of my life. And I like to believe that in those final overs, I bowled not with my arm but with my heart.'

On His Knighthood and Recognition

He paused then, shoulders rolling as though shedding an invisible weight. 'The knighthood? Ah, that came in 2012. Some say too late, perhaps unjustly delayed. Many of my brothers had already felt the sword upon their shoulders, Sir Frank Worrell, Sir Garfield Sobers, Sir Everton Weekes, Sir Clyde Walcott, Sir Vivian Richards. Giants, all of them, men who brandished the bat as if it were a sceptre. But me? I was a bowler, a man who came with nothing but pace, sweat, and a smile. And after Alec Bedser, they say I am only the second bowler to be knighted purely for what the ball did in my hand. Forty years after my last Test. Forty years! But, Docr, what is time to a man who has already given his life to God?'

Then his eyes lit again, twinkling with that irrepressible grace. 'It never bothered me. I never chased it. As Frank Worrell, my captain, my mentor, once said: Unlike most fast bowlers, Hall speaks of cricket in every way but the first person singular. That is the truth of me, Doctor. Ego was never my bowler's mark. I never wanted to be the terror in the batsman's dreams, only the joy in the spectator's memory. So when the sword finally touched my shoulder, I bowed my head not for myself, but for the game, for the islands, for the people who sang my name.'

And finally, with a soft smile: 'Sir Wesley Hall, they call me now. But the title I cherish most is not knight, nor minister, nor president. It is simply this: a man with fire in his bowling arm and kindness in his heart.'

On His Complete Cricket Legacy

Sir Wesley Winfield Hall played 48 Tests for the West Indies and was more than just a spearhead; he was a presence, the embodiment of a cricketing nation learning to roar. He shared new-ball spells that left batsmen groping, sometimes with Roy Gilchrist, sometimes with Charlie Griffith, and always with the weight of history gathering behind him. Yet pace alone did not define him; his generosity of spirit did. The man who could frighten the finest batsmen also possessed a heart that recoiled at malice, a paradox that made him both fearsome and beloved.

But cricket was only the beginning. Once the roar of the crowd dimmed, Hall slipped easily into other roles, as though his life had always been destined for reinvention. Selector, manager, Board President, each position carried his imprint of energy and empathy. Beyond cricket, he rose to serve his people, appointed as Barbados's Minister of Tourism and Sport, where his oratory, famously compared by him to his run-up in length, carried the same cadence of conviction.

Years later, when the sword of knighthood finally touched his shoulder, it was less a coronation than a confirmation: that this son of Barbados, who once made batsmen flinch and crowds adore, had given back as much to society as he had to the game. Wes Hall was no longer just the bowler with the endless run-up. He was a knight, minister, elder, and always, always, the man with fire in his arm and grace in his soul.

On His Early Cricket Journey

Sir Wesley, with that unmistakable cadence, half-sermon, half laughter, began unravelling the thread of his story. 'Doc,' he chuckles, 'you know, I didn't begin this journey with fire in my arm. I began crouched low behind the stumps, a boy from Saint Michael, son of a light-heavyweight boxer, with gloves on my hands and dreams in my head. At St Giles' Boys' School, and later Combermere, yes, Combermere, the cradle that raised so many of us, it was the scholarship that carried me there, and the grace of fortune that put me in Division 1 cricket. There I stood among men long before I was one, keeping wickets to Frank King, who himself would go on to play fourteen Tests for the West Indies. Imagine that, two boys in whites, side by side, not knowing the future that lay in waiting.' He paused, as if still seeing the dusty fields of Barbados, then continued.

'After school, life had a different plan. The Cable office in Bridgetown took me in, a steady job, wires buzzing, telegraphs humming. But cricket has a way of finding you even when you think you've tucked it away. Their team needed hands, and I gave them mine. That was where it began, no longer behind the stumps, but at the top of a run, charging in, ball in hand, discovering that I could send it down like lightning. It wasn't a calling at first, just an accident of chance. But accidents have a way of shaping destinies.'

His voice softened, but the glint in his eye sharpened. 'They say I was the first genuine fast bowler the West Indies had after the war, the first tearaway, the first to truly bowl with that pace like fire. CLR James would later write of it, and my own autobiography would scrounge the phrase. But back then, it was not history, it was just me, a tall boy with a heavy stride and a heart that beat a little quicker when the batsman looked uneasy.'

A wide grin spread across his face, as if he was replaying the familiar rhythm in his head. 'And, the run-up, Doc, you must have seen it, or at least heard of it. Long enough to make you think I was training for the marathon, not bowling in a cricket match. Long run-up, longer follow-through, a crucifix swinging on my chest as if leading the charge, arms cartwheeled, eyes blazing. Some said it was theatre, others said it was terror. Me? I just thought it was joy. The Lord gave me height and stride, so I used them both. That was my canvas, Doc. Every ball, a brushstroke.'

On His Career Highlights and Achievements

I asked him with the curiosity of a historian, but Wesley answered with the warmth of a preacher who has lived it all, his voice equal parts memory, laughter, and the faint tremor of time's weight. 'Doc, you ask me about Wisden. Yes, the little book that anoints immortality. I was never one of its Five Cricketers of the Year. Strange, isn't it? A man could bowl until his knees gave way, shake batsmen from their comfort, even taste the blood and dust of history's first tied Test, and yet, still, not there. But let me tell you something: paper does not bind the spirit. I shared the absence with Jeff Thomson, with Bishan Singh Bedi, with Abdul Qadir, and even Inzamam Ul Haq. Not bad company? I never lost sleep over it. History has many doors; not all open in the same hallway.'

His tone deepened, and suddenly you could hear the roar of the Gabba in his chest.

'1960, Brisbane. The match that refused to die refused to yield. I sent down 17 overs that final day, and the last one became legend. Six runs Australia needed. Three wickets fell. Two were run outs. The game tied, history written in the sweat on my shirt. Four for 140, five for 63, and still the memory that people hold close is of that over. Doc, that was not bowling, it was theatre, it was a storm bottled into six balls.'

'They say fast bowlers hunt in pairs, and I was blessed twice. First with Roy Gilchrist, whose fire could make even the bravest batsman think twice. Wisden said we were the new Constantine and Martindale, two men with the sun at their backs. Then came Charlie Griffith, my brother in arms. Together, we became the axis of victory, the very centrepiece of West Indian triumph. To share that fury, to know another's rhythm, that was not just cricket, that was communion.'

His eyes narrowed, remembering Lahore. '1959, Lahore. My first hat-trick, the first by a West Indian in Test cricket. Mushtaq Mohammad, Fazal Mahmood, Nasim Ul Ghani, they went in a blur. Five for 118 in the match, and Pakistan, proud and unbeaten at home until then, humbled by an innings and 156. For me, Doc, it was not numbers. It was that sudden gasp of silence in the crowd, the kind only cricket gives when destiny sneaks in without warning.'

'And then, Lord's 1963. England's cathedral, their home. Two boiled eggs in my stomach, nothing more, and 200 minutes of bowling unchanged. Four for 93, Colin Cowdrey's arm broken. The crowd stood, the ground breathed with me. Those were the hours when body, spirit, and crowd fused into one. That day, I did not bowl, I endured, I gave myself entirely.'

On His Life's Multiple Phases

'By 1990, Doc, I had bowled my overs in life's first act. It was time to surrender to a higher call. I gave my heart and life to God. Bible school taught me to speak with the same conviction with which I once ran in. They called me fast once, but with Malcolm, my dear Malcolm Marshall, it was slow, tender work. To sit by his side as cancer bit him, to minister his spirit even as his body failed, that was my fiercest test, Doc. Pace could not help there. Only prayer.'

'I found myself in Barbados' senate, later minister of tourism and sport. I used to joke You thought my run-up was long? You should hear my speeches! But in truth, I saw it as another crease, another wicket to defend, this time for my people. To serve them was to bowl with a new purpose. I was not done with the game either. Managed the West Indies team, sat as a selector, and even presided as board president. The fire never leaves you, Doc, it only finds new vessels. My run-up became meetings, my overs became decisions, but always the aim was the same: to see West Indies shine.'

'They gave me halls of fame, doctorates, and stands with my name etched beside Griffith. The Caribbean Tourism Organisation tipped its hat. But the moment they placed the sword on my shoulder in 2012, that was the final over of my career. Sir Wesley, they called me. Yet as Sir Frank Worrell once said, I never spoke of cricket in the first person. The honour was never mine alone. It belonged to every boy barefoot on the sands of Barbados, to every crowd that cheered us.'

'And through it all, Doc, I remained what God allowed me to be, a man who loved laughter. They said my popularity crossed oceans, that in Melbourne they welcomed me as if I were a pop star. Me? I was only a cricketer, a husband, a father of three, a servant of faith. Cricket was my stage, but life… life was always the bigger play.'

Photo caption: Dr. Nauman Niaz —with the Fire Power Pioneers—Wesley Hall & Charlie Griffith in Barbados, 2000.

Dr. Nauman Niaz, one of Pakistan’s most renowned cricket broadcasters, has interviewed some of the world’s biggest cricketing personalities during his extensive career. A civil award recipient (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, he has covered 54 international tours and three ICC World Cups as a correspondent, while contributing over 3,500 articles to leading publications. The author of 14 books and the official historian of Pakistan cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes, four volumes, 2005), Dr. Niaz is best known for his signature show Game On Hai, which has consistently topped ratings and earned widespread acclaim. Now, he shares his journey and experiences exclusively with JournalismPakistan.com readers.