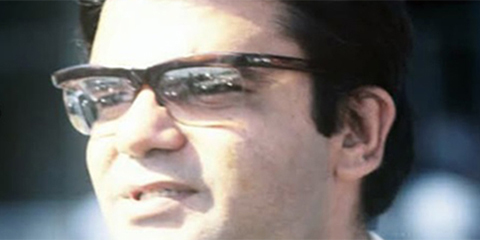

Chishty Mujahid: The voice that defined Pakistan cricket commentary for generations

JournalismPakistan.com | Published 3 months ago | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

ISLAMABAD—I grew up with voices before I grew up with faces. The radio was my first companion, its invisible words sketching fields of green and men in white upon the canvas of my imagination. Then came 1978–79, when Pakistan Television carried every ball of India's tour into our homes, and with it, the grandeur of a moment: two nations resuming a conversation in cricket after seventeen years of silence. For me, it was less about the contest and more about the voices that carried it, a symphony of accents, cadences, and tempers, Urdu and English weaving two distinct fabrics of the same match.

The Golden Era of Pakistani Cricket Commentators

They were not just commentators; they were conjurers of words. Munir Hussain, Hassan Jalil, and Mohammad Idrees brought Urdu's richness, while in English there stood giants: Omar Kureishi with his incisive wit, sharp as glass yet elegant as rhymes; Iftikhar Ahmad, a corporate grandee, verbose and ornate, layering synonyms as though splashing colour upon a canvas; Shahzad Humayun, Oxford in tone and accent, refined and stately; Tariq Rahim, gentlemanly in pulse, his sentences structured as though measured by contours; and Chisty Mujahid — whose connectivity, flamboyance, and Cambridge polish set him apart. A leg-spinner once, his commentary had the rhythm of the googly: measured, surprising, always arriving from an unexpected angle.

Chishty Mujahid: More Than Just a Cricket Voice

Chisty was more than a voice; he was a presence. He could host, administer, and anchor, but his true genius lay in his economy of words, punctuated by pauses that carried weight. He gave players back their full names, stretching them into epics, Chaminda Vaas as Warnakulasuriya Patabendige Ushantha Joseph Chaminda Vaas. To me, the boy who once mimicked those voices in his bedroom, it was a benediction to sit beside them, Omar, Chisty, Shahzad, Tariq, no longer only idols but companions. And yet, Chisty remained singular: affectionate, witty, laced with satire and the ease of British humour. He was life condensed into speech, a mentor, a raconteur, a man whose laughter still echoes through the memory of generations. Voices fade, faces depart, but men like Chisty Mujahid remain: part of the great chorus of cricket, where commentary itself becomes literature, and memory is carried not in pictures, but in sound.

From Delhi to Karachi: The Making of a Cricket Legend

Chishty bin Subh-o-Mujahid was not born into cricket; he was born into its silences, into the pauses between a bouncer and a cover drive where meaning is often found. From Delhi's dust in 1944 to Karachi's restless sea, his journey mirrored that of a nation itself, fragmented, migrating, rebuilding. By the time he took up the microphone in 1967, he had carried with him not just the cadences of Karachi Grammar, or the polish of Selwyn College, Cambridge, but the yearning of a young Pakistan seeking its voice. And in cricket, he found it.

The Philosophy of Cricket Commentary as Literature

To generations, Chishty Mujahid was not only a commentator; he was the interpreter of afternoons, the guardian of detail, the architect of memory. His words were not thrown but weighed, precise yet generous, as though he understood that the game was not only an event but a scripture. His pauses mattered as much as his sentences, teaching us that silence too has commentary. His impact did not lie only in the prizes, the PTV Best Sports Commentator, the Pride of Performance but in the countless young boys who mimicked his tones, who learned that to speak of cricket was to speak with reverence, with wit, with humanity intact.

The Lasting Legacy of Pakistan's Greatest Cricket Commentator

His legacy is less in archives and more in philosophy. He embodied the idea that cricket was never only about victory or defeat but about memory, the game as it lives in us long after the scoreboards dim. He gave generations a way to remember, a way to narrate, a way to see. And in doing so, he became not merely a chronicler of cricket but a chronicler of us, of who we were when we watched, when we listened, when we believed that words could make a boundary feel eternal. That is his gift: the philosophy that sport is not the escape from life, but its echo, and in every echo of Chishty Mujahid's voice, generations after still find themselves.

From Radio Pakistan to International Recognition

At twenty-three, when most are still finding their footing, Chishty Mujahid found his voice. He slipped behind the microphone at Radio Pakistan, first part-time, though in truth it was less an occupation and more an inevitability. By 1970, his intonation had migrated to television, carried by the state's new window into the game: Pakistan Television. From there, his voice began its long journey, carried across borders and oceans, to Doordarshan and Rupavahini, to Sony and Worldtel, to the BBC's Urdu Service, to South Africa and the Gulf. Wherever Pakistan cricket went, it seemed, Chishty's words followed, not as a shadow but as a companion. He was not only a commentator; he was a chronicler of a nation's sporting heartbeat, his sentences becoming the rhythm with which millions remembered the game.

Awards and Recognition: A Career Decorated with Honor

Recognition arrived, but almost as an afterthought. Three consecutive nominations for PTV's Best Sports Commentator in the mid-80s, with the award itself claimed in 1986. Radio Pakistan's highest honour in 1999. The Excellence Award in 2001. And then, in 2003, the President's Medal for Pride of Performance, a rare, almost monastic honour, was shared by only a handful of his peers. Yet these were milestones, not the essence. His true accolade lay in the way children mimicked his tones in alleyways, in how his pauses carried the drama of cricketing afternoons into living rooms, in the way his words became tethered to memory itself.

Destiny had other designs: cricket, which he could not play at its highest level, he would instead narrate, shape, and immortalise. And so, the boy who once earned a cricket set only by topping his class became the man whose words gave cricket in Pakistan its class, its memory, its permanence.

Learning from the Masters: John Arlott's Influence on Pakistani Commentary

He had grown up listening to the rolling cadences of John Arlott, the crispness of Brian Johnston, the authority of Peter West. In England, those voices were a kind of scripture, teaching him that cricket could be spoken as art, as theatre. When he returned to Pakistan, there was no television yet, only the disembodied intimacy of radio. He applied to Radio Pakistan, auditioned, and though his knowledge of cricket was modest and his voice only 'tolerable,' something in him fit the airwaves. In 1967, at under twenty-three, he made his debut. It was a game in Hyderabad, Sindh: MCC Under-25, led by Mike Brearley, against South Zone captained by Hanif Mohammad. From that moment, he was no longer just a listener of voices he had become one.

Balancing Corporate Life with Cricket Commentary Passion

Yet commentary was never a livelihood; it was a calling pursued at cost. Cricket in Pakistan then was not as relentless as it is now, but occasional, fleeting, and commentary brought no riches. His father, still hoping for a lawyer, watched his son drift into what seemed no more than a hobby. And so he worked: Glaxo, Unilever, SmithKline, Apple, Unisys, the great multinationals of the age. His leave days were not for holidays but consumed in pursuit of the microphone, each tour a pilgrimage that emptied the pocket but filled the soul. He owed much to his family, particularly his wife and daughters, who endured the weight of sacrifice so he might continue to speak of the game he loved.

The Art of Cricket Commentary: Memory as Literature

At work, he carried a strange duality. To some, his public voice brought advantage: doors opened, government offices softened, reputations lent weight to business. To others, it stirred envy: whispers to bosses that this man did no work, that cricket was his only occupation. But he endured, because he was sustained not by acclaim but by memory. His commentary was a weaving of record and recollection, his mind a library built not on research assistants but on years of Wisden, Playfair Annuals, and volumes of literature. He remembered the game because he had read it, lived it, and, like literature, carried it within him. Shakespeare, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Ghalib, Iqbal, Mir, he could still summon their words as he once summoned scorecards. Old age may fade memory, but the philosophy of it remains: that commentary was never statistics recited, but literature performed, cricket narrated as if it were always meant to be written, not merely played.

The Legendary Ifti-Chishty Partnership on Pakistani Airwaves

In the 1970s, for those who first came to cricket through the airwaves, the game was not just bat and ball, but voice. And few partnerships linger in memory quite like the duet of Chishty Mujahid and Iftikhar Ahmad — the 'Ifti–Chishty' tandem. They were distinct yet complementary: Chishty's measured cadences and silken pauses beside Iftikhar's flamboyance and flourish. Even now, decades later, their bond remains, though the years have yielded space to younger voices. Iftikhar has since made his home in Canada, while Chishty has never left Karachi, both men tethered still by the long arc of shared commentary boxes, from the days of Radio Pakistan to more modern and aesthetically impactful television coverage.

When Cricket Commentary Was an Art Form

Back then, the listener had no choice; Radio Pakistan, later PTV, were the only conduits into the game, and so their voices became the sole windows through which millions imagined cricket. Today, the glut is endless, FM channels, 24-hour coverage, a match forever happening somewhere. In such excess, their modesty stands out. They never advertised themselves, never wore fame with loudness, but spoke of commentary as addiction: stronger than passion, fiercer than religion. To them, cricket without commentary was incomplete, not the same game at all. And when they meet now, over tea or lunch, their friendship holds, even if they watch the new guard take the field.

The Classical Standards of Cricket Broadcasting

The philosophy of their era was simple: a commentator was not just a former cricketer pushed to a mic. He was a student of cricket, of broadcasting, of cadence. Knowing when to speak, when to hold silence, how to let a voice rise or fall, these were as important as knowing a cover drive from a late cut. Chishty often pointed to Richie Benaud, trained in commentary long before he was let loose on air, as the model. Theirs was a world of precision: accent mattered, pronunciation mattered, expression mattered. Today, the floodgates are open, and that has its charms too, but there was something sacred in their craft, something exacting. And through it all, Chishty remained the same: a voice not chasing celebrity, but shaping memory where cricket became not just watched, but narrated into permanence.

Unforgettable Cricket Moments Through Chishty's Eyes

There are stories in cricket that seem less fact than parable, their truth embroidered by awe. Hanif Mohammad's 337 was one such epic. He batted for days, and those who watched carried tales almost mythic. One man, perched on a tree outside the ground because he could not get in, fell from his branch in sheer exhaustion after watching Hanif grind bowlers to dust. Patched up in the hospital, he returned days later, climbed again, and saw Hanif still there, still batting. He fell off once more, stunned by the sameness of it. Was it 960 minutes or 999? Numbers quibble, but minutes blur into eternity when endurance itself becomes the story.

## Witnessing Cricket's Greatest Performances

There were other spells that etched themselves into memory. Imran Khan, Karachi, early 1980s, the ball in his hand shaped and dipped like a conjurer's trick. Gundappa Viswanath, elegant and precise, shouldered arms outside off stump; the ball returned like a boomerang to take leg. Shock, stupor, disbelief, even the finest batsmen were made vulnerable when Imran bent the laws of physics to his will. And then there were journeys across the globe: to Zimbabwe, where in the beginning locals asked them, half in innocence, 'What cricket union?' Later, Zimbabwe would give the world the Flowers, Alistair Campbell, Heath Streak, Paul Strang, Eddo Brandes, Murray Goodwin, Henry Olonga, fine players who suggested what might have been, had circumstances allowed.

The Evolution of Cricket Commentary: From Art to Entertainment

But memory also carried lament. The old standards of commentary, once shaped by the gravitas of broadcasters trained in cadence and restraint, had waned. Where once silence was allowed to breathe, now television filled every gap with chatter, radio commentary masquerading on screen. The art of describing weather, atmosphere, even the colour of a sleeveless sweater, was replaced by a relentless obsession with the score, repeated like a mantra. And yet, he said, perhaps this too was inevitable. The game had changed; money, television, and spectacle had reshaped it. Cheerleaders, film stars, and the tamasha of modern leagues had redefined what cricket was meant to look like. To the classicist, Test cricket remained the last refuge of purity, its slow burn the only theatre that still resembled the game as it once was. And in that tension between memory and modernity lies the story of cricket itself, forever pulled between what it has been and what it is becoming.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has been the highest in ratings and acclaim.