Pakistan's red-ball riddle: Understanding the Test downturn (I)

JournalismPakistan.com | Published: 9 January 2025 | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

Dr. Nauman Niaz explores the challenges and historical context behind Pakistan's Test cricket downturn. The article examines recent performances, notably the second Test against South Africa, revealing systemic issues hindering the team's success.Summary

This insightful article by Dr. Nauman Niaz marks the beginning of a compelling two-part series that delves deep into the intricate world of Pakistan's Test cricket. Through his expert analysis and profound understanding of the game, Dr. Niaz unpacks the historical evolution, defining moments, and the current state of Test cricket in Pakistan. Readers can look forward to a comprehensive exploration of the challenges, triumphs, and nuances that have shaped Pakistan’s journey in the longest format of the sport.

Pakistan’s Defiance at Newlands 2nd Test 2024-2025

Pakistan’s valiant attempt to overturn a daunting deficit of 421 in their second innings at Newlands, Cape Town, was reflective of their resilience, and grit, and, in this rare instance, their captain Shan Masood’s inspirational work, was exemplified by his impeccable 145. The enormity of their task was set by the ignominy of being routed for a paltry 194 in the first innings. Yet, in the face of this adversarial landscape, Babar Azam, with a masterful 81, joined Masood to sculpt a monumental partnership, a record-breaking 205 for the first wicket, that stood as a source of defiance against the inexorable surge of adversity.

However, in the narrative of their endeavor, moments of frailty surfaced, punctuating an otherwise dauntless resistance. Babar’s imprudent shot at the twilight of Day 3 unraveled a carefully threaded hope, and Mohammad Rizwan’s miscalculation, forsaking pragmatism at a time when his stand with Salman Ali Agha was blossoming, represented costly aberrations. Yet, their collective toil spurred them to an admirable total of 478, simply spectacular. For South Africa, the completion was but an ephemeral formality. A target of 58, trivial by any standard, was attained with almost perfunctory ease, requiring merely 7.1 overs to seal a comprehensive victory. This Test was a distressing reminder of the paradoxical beauty of the sport: where resilience is celebrated, yet fragility magnifies the evanescent nature of glory; where triumph and toil coalesce into one precious moment, fugacious yet eternal in its resonance.

In a triumphant display that underscored their clambering to the World Test Championship final, South Africa celebrated their seventh consecutive Test victory. The match, a microcosm of grind, drudgery, and triumph, witnessed two and a half days of implacable labor as South Africa bowled Pakistan out for a defiant 478 in the third innings. A resplendent century from Pakistan’s captain, Shan Masood, coupled with tenacious contributions from Babar Azam, Mohammad Rizwan, Salman Ali Agha, and Aamer Jamal’s was an unforgettable interlude of defiance. Pakistan, rising against the surges of a daunting first-innings deficit compelled South Africa to bat once more. Keshav Maharaj’s Predicament

The narrative of the match, however, is not encapsulated solely in its conclusion. Pakistan, expressing the spirit of cricket’s indomitable ethos, drove South Africa to prolong their quest for victory. Enforcing the follow-on with an overwhelming lead of 421 on a languid Sunday afternoon, South Africa scarcely anticipated the arduous toil of an additional 122.1 overs. Masood, steadfast at 102 overnight, endeavored to rekindle his team’s prospects, building upon the foundation of an epic opening partnership with Babar Azam. South Africa’s bowlers, though, faced prolonged frustration, most distressingly during an 88-run stand between Mohammad Rizwan and Salman Agha that frustrated them for much of the afternoon. Yet, Keshav Maharaj, thwarted for the better part of the day, finally shattered the resilience, paving the way for wickets to tumble under the waning sun.

Earlier, the day had commenced with Marco Jansen ousting nightwatchman Khurram Shahzad, while Kagiso Rabada cleaned up Kamran Ghulam in a spell of absolute fire. Keshav Maharaj, a bowler of undoubted pedigree, laboured through his craft, delivering a performance far removed from the full measure of his prodigious talents. His 3-137 in 45 overs stood as a pale reflection of his usual brilliance, a testimony to the intangible interplay of form, fitness, and circumstance that controls the sporting realm. His average release speed of 76.4 kph, on a pitch as placid and slow as Newlands, ought to have exceeded 80.0 kph. Yet, the dynamics betrayed him further; his delivery speed dipped to an anomalous 56.6 kph, when ideally it should have rested between 60 kph and 65 kph. By the time the ball reached the batsman, its velocity had diminished to 52.4 kph, a number that fell woefully short of the optimal range of 55 kph to 60 kph.

Though Maharaj managed picking wickets towards the end, the subtle betrayal of his body was evident in every delivery. His bowling arm, bereft of its usual vigour, failed to rise above the shoulder with any regularity, the undercut trajectory of his deliveries a stark indication of his physical limitations. The lingering shadow of recent injury loomed large over his performance, a poignant reminder of the precarious balance between recovery and readiness. In the grander scheme of cricket’s narrative, Maharaj’s plight invites reflection on the fragility of human endeavour.

It was pace that seized the day. Shahzad’s fleeting vigil ended as a length ball from Jansen reared sharply, inducing a miscue to Maharaj at point. Kamran Ghulam, unsettled from the outset, succumbed to Rabada’s mastery, a delivery that nipped back off the seam, dismantling the middle stump in a moment of absolute precision and sluicing, his 50th Test wicket at Newlands amidst a rapturous loudening.

Shan Masood’s epic resistance ended amid controversy. Kwena Maphaka’s delivery, deceptively subtle that kept low, trapped Masood, whose protestations against the verdict lingered long after the review revealed Hawk-Eye’s decision. His exit wasn’t only a loss of a wicket but subsiding of a surge that had momentarily welled up against overwhelming probabilities. Salman Agha and Mohammad Rizwan rekindled hope, chiselling away at the deficit with an uncompromising resolve. Their partnership, punctuated by deft rotation of strike and prudent boundaries, characterized calculated resistance. But South Africa’s patience, unswerving and unbroken saw Rizwan’s mistimed chip found short cover, and Agha, reprieved momentarily by DRS, succumbed to Maharaj’s spin.

The completion, orchestrated with clinical precision, saw Mir Hamza’s brief pyrotechnics light the twilight moments, but the innings was swiftly wrapped up. South Africa’s openers, unburdened, avoided prolonging the match into the next day. David Bedingham’s breezy, 47 not out from 30 balls represented the spirit of unbridled freedom, concluding the match in 43 deliveries.

Story of Contents and Capitulation

In this story of contest and capitulation, Pakistan’s defiance, though ultimately in vain, resonates as a paean to cricket’s enduring capacity to inspire. This match also reflected how pedestrian has been their run in Tests. It’s true, Shan Masood’s defiant century, his sixth in Test cricket, symbolised a brief yet poignant resurgence. However, Pakistan’s inability to secure a victory underscored a larger systemic malaise. With Shan losing eight out of ten Tests as captain and Pakistan failing to compete against weaker teams across all formats, the rot extends beyond the field. Rapid changes in leadership at the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB), irrelevant appointments, and bureaucratic inefficiency reflect an institutional collapse that parallels the decline in the team's performance. Pakistan cricket's narrative, once defined by moments of brilliance and stubborn defiance, now teeters on the brink of mediocrity. Here we examine the intersection of sporting failure and administrative mismanagement, painting a picture of a nation struggling to reconcile its cricketing identity. Pakistan’s abysmal record in Australia and South Africa since 1999 is dismaying, 29 losses in 30 Tests over 11 tours, encapsulates a deeper malaise afflicting its cricketing landscape. Countries like India revolutionized their cricket through impenetrable planning, intellectual honesty, professionalism, modern infrastructure, rigorous meritocracy, and player development. Pakistan has clung to a cycle of self-denial and illusions, consequences of stagnation and misplaced nostalgia, juxtaposing their descent with India’s ascent. We delve into how Pakistan’s cricket symbolizes a national identity mired in contradictions, hankering for past glories yet unwilling to evolve. The analysis reflects on what it means for a cricketing nation to lose not just matches but its capacity to dream realistically.

A Philosophical Reflection on Losses and Stagnation

Cricket is more than just a game; it is an intricate alliance of ambition, preparation, and adaptability. For Pakistan, a country that has always prided itself on cricketing flair, the haunting record of 29 losses in 30 Tests in Australia and South Africa since 1999 tells a story of systemic collapse. To lose is human, but to lose repeatedly and in the same manner insinuates a deeper flaw, a refusal to confront reality, to evolve in the face of adversity.

Australia, with its hard pitches, and South Africa with bouncy wickets, the ruthless crowds, and unforgiving cricket culture, has always been the litmus test for touring teams. For Pakistan, it has been a nightmare, countries where dreams go to die. The lone victory, during this period was attained in 2007 at Port Elizabeth, now known as Gqeberha, stands as a relic of a bygone era, a time when Pakistan’s cricket thrived on raw talent and instinct. But cricket has moved on, and so have its powerhouses.

India, Pakistan’s historical and emotional rival, suggests a sharp contrast. Over the past eighteen years have modernized its cricketing ecosystem, investing in state-of-the-art infrastructure, nurturing talent through grassroots programs and pathways, and adhering to merit. The Indian Premier League (IPL) became a global phenomenon, not just a commercial juggernaut but a breeding ground for world-class players. Not only the IPL they also revitalized the Ranji, Duleep, Syed Mushtaq Ali, Colonel C.K. Nayudu, Cooch Behar, Deodhar, Irani and Vijay Merchant trophies by infusing adequate money, restructuring and re-modelling their pathways, integrating latest tools and developing top class human resource. India’s triumphs in Australia, culminating in historic series victories in 2018-19 and 2020-21 were not accidental but the fruits of foresight, planning, and hard work.

In contrast, Pakistan cricket has remained ensnared in illusions. It romanticizes its glorious past while failing to lay the groundwork for a sustainable future. The self-denial is palpable: the belief that raw talent alone can triumph over preparation, that sporadic moments of brilliance can compensate for systemic inefficiencies. The result is a cricketing culture that is reactive rather than proactive, dependent on luck rather than planning. The broader implications of this stagnation are philosophical. Cricket demands evolution. A team, much like an individual, must adapt to changing circumstances or risk obsolescence. Pakistan’s refusal to modernize its cricketing structures reflects a national psyche reluctant to embrace change. Bureaucratic inefficiency, nepotism, and a lack of accountability have corroded the foundations of its cricket. Infrastructure remains outdated, grassroots programs are underfunded, and merit is often sacrificed at the altar of political expediency.

This inertia has far-reaching consequences. For a nation where cricket is more than a sport, a symbol of unity, hope, and national pride, the continued failures across all formats strike at the heart of its identity. Each defeat is not just a loss on the scoreboard but a reminder of unfulfilled potential, a symbol of what could have been. Yet, there is a paradox in Pakistan cricket. Despite its failings, it retains an almost mythical allure. The world remembers the mastery of a Wasim Akram yorker, Waqar Younis’ poetic run up and an astounding strike rate, Shoaib Akhtar’s dreading speed, Imran Khan’s charisma, the magic of a Saqlain Mushtaq doosra, the audacity of an Inzamam-ul-Haq stroke, consistency of Mohammad Yousaf, natural flair of Saeed Anwar, acrobatics and kinesthetics of Rashid Latif, and Younis Khan’s workmanlike attitude. But these memories, while comforting, have become the shackles, trussing Pakistan cricket to an idealized past. To move forward, Pakistan must let go of this nostalgia and confront the present with honesty and courage.

The road to redemption begins with acknowledging the problem. Pakistan must invest in infrastructure, adapt data-driven analysis, and develop a transparent, merit-based system. The talent is there, it always has been. But talent without structure is like a river without banks; it meanders aimlessly, incapable of forging a path. The story of Pakistan cricket is not just about losses; it is about the cost of stagnation. It is a cautionary story of what happens when a nation clings to illusions instead of striving for progress. But within every tale of despair lies hope. Pakistan, with its rich cricketing heritage, has the capacity to rise again. But to do so, it must confront its flaws, shed its illusions, and acclimate the hard but necessary work of transformation. For cricket proffers second chances, but only to those brave enough to seize them.

A Philosophical Reflection on the Struggles of Identity and Defiance

There is something inherently tragic about the fall of a giant. Pakistan cricket, a symbol of ingenuity, passion, and raw talent, has long been a canvas for stories of resilience and rebellion. Its history is marked by moments of defiance that have excelled sport, a 1992 Benson & Hedges World Cup victory against all odds, a triumph in the ICC T20 World Cup in 2009, a 2017 Champions Trophy triumph over arch-rivals India, and countless instances of individual brilliance. Yet, as the sun sets on its unique legacy, one is compelled to question whether Pakistan cricket has lost the essence of what once made it great.

The recent Test against South Africa at Cape Town offers a microcosm of this existential struggle. Pakistan would not go quietly into the night. Yet, despite this act of heroism, the team succumbed to defeat. The story is one of defiance marred by inevitable collapse, a familiar motif in Pakistan’s cricketing narrative.

Masood’s resurgence, ending a nine-innings run drought, was bittersweet. His tenure as captain has been marked by failure, losing eight of the ten Tests. Bowlers, once the pride of Pakistan and often heralded as the best in the world, has conceded five totals exceeding 600 runs in the past five years. At home, a supposed fortress, the team has won only two of its last 13 Tests at home . Losses to traditionally weaker teams such as Bangladesh, Zimbabwe, Ireland, and even the USA across all formats have only deepened the sense of despair.

But the malaise extends far beyond the field. Pakistan cricket’s decline is not just a tale of missed catches and poorly judged run-outs. It is a reflection of a crumbling institution, plagued by incompetence and corruption. The Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB), ostensibly the custodian of nation’s cricket, has become a revolving door for chairmen and officials. Bureaucratic ruthlessness has replaced merit; hotel management and undergraduates working as Director International cricket, lawyers acting as Chief Operating Officers, and self-proclaimed data analysts, ignorant of the fundamentals of statistical science, dominate decision-making processes.

The heart of the problem lies in this dissonance between what Pakistan cricket aspires to be and what it has become. A nation that once prided itself on producing world-class talent now struggle with diploma holders running its medical panel. Players lack access to modern equipment and tools, their careers derailed by short-sighted, uninformed decision-making. The system, much like the team, is adrift, untethered from the values of excellence and resilience that once defined it.

Philosophically, the plight of Pakistan cricket mirrors a broader struggle with identity. Cricket in Pakistan has always been more than a game; it is a source for national pride, a medium through which a fragmented nation finds unity. Cricket was a stage where dreams were not just dreamt but realised. Today, it has become a battlefield of mediocrity, where hope is perpetually extinguished by systemic dysfunction. Yet, as bleak as the present may seem, Pakistan cricket has always been a story of revival. It has risen from match-fixing, and ball tampering scandals, intrigues, rebellions, and international isolation to reclaim its place among the elite. The current crisis, however, demands more than individual brilliance or ephemeral moments of defiance. It requires introspection, a philosophical reckoning with what Pakistan cricket stands for and what it seeks to become.

Shan Masood’s 145 at Cape Town, though ultimately in vain, is a reminder of what is possible. It is a call to rediscover the resilience that lies at the heart of Pakistan cricket. For in that act of resistance, there is a glimmer of hope, a hope that, perhaps, this is not the end but could be the beginning, only if rectification is warranted. To rise again, Pakistan cricket must confront its torments, sprights and anxieties, not just on the field but in the corridors of power where its fate is truly decided. Only then can it reclaim its identity and, with it, the respect and admiration of the cricketing world.

Cricket, like the societies it both mirrors and transcends, often finds its essence obscured within the labyrinth of contradictions and failures. The Pakistan Test team's recent descent into disarray, epitomised by a captain who valiantly scores a century amidst despair yet cannot forestall the wreckage around him, offers a poignant narrative, a theatre of human struggle, where ambition is thwarted by incompetence, and leadership becomes an onerous task. Yet his personal triumph illuminates, rather than mitigates, the malaise of the team he leads, a team that has lost eight of its last ten Tests, the captain himself shackled to the operose burden of inspiring those incapable of responding in kind.

Central to this collapse is the absence of foundational elements, those irreplaceable cogs that lend rhythm and balance to the machinery of a cricketing team. The lack of quality openers, save for the impactful brilliance of Saim Ayub, whose injury further exposes the fragility of the system, leaves their cricket perpetually unmoored. The fast bowling stocks, traditionally Pakistan’s resource of intimidation, have degenerated into mediocrity, bereft of any spearhead capable of breaching the psychological barrier of 140kph. This erosion is not only a matter of talent but a symptom of systemic negligence, an inability to cultivate and nurture the raw firepower that once circumscribed the nation's cricketing ethos.

Selections, meanwhile, oscillate between the whimsical and the myopic, an imbalanced team emerging as the natural consequence of poor judgement. The unpredictability and transientness of the management compounds the disarray, creating a culture of ephemerality where neither players nor administrators can lay the foundations of stability. The very concept of a ‘team’ disintegrates into a collection of individuals, each wrestling with their insecurities, their failures magnified by the absence of collective purpose.

Yet, this narrative cannot be confined to the cricketing realm alone. It mirrors deeper existential struggles, of identity, cohesion, and the paradox of leadership in a fractured world. The captain’s predicament is a microcosm of the human condition: to lead with conviction while navigating the perpetual dissonance between individual agency and collective ineptitude. Masood’s century at Newlands is thus a philosophical statement, a lone flourish of beauty in a landscape marred by chaos. It speaks to the profound loneliness of leadership, where even the greatest efforts are often swallowed by the mediocrity of those one seeks to uplift. Above all, was his installation as Pakistan’s captain merited. He hardly deserved to be the part let alone leading Pakistan in Tests. He never deserved to be the captain, and he was elevated when he had hardly been in the runs, his pedestrian averages weren’t not an ideal advertisement of merit.

The disintegration of Pakistan’s Test team is not only a outcome of poor cricket. It is a study in fragility, the fragility of systems, the fragility of trust, and the fragility of human ambition when untethered from collective harmony. The absence of fast bowlers capable of evoking fear, the injury-stricken promise of a lone opener, Saim Ayub, and the whimsicality of selection processes, all these are but symptoms of a larger cultural malaise, where talent is squandered, and vision is perpetually deferred, if any.

Perhaps, in its despair, this story offers a lesson. It is a reminder that cricket thrives on balance, a balance between individual brilliance and systemic support, between audacity and prudence, and between past glories and future aspirations. The captain’s hundred at Newlands is a call to introspection, a plea for recalibration, and an assertion that even amidst ruins, the human spirit is capable of moments that outdo failure. But moments, however idealistic, cannot sustain a disintegrating edifice. Without structural reforms, without the courage to face up to mediocrity and the imagination to envision excellence, Pakistan’s Test cricket risks becoming an apparition of its past, an emotional relic of what once was, and a cautionary story of what might have been.

The Erosion of Excellence

The history of cricket, like that of any quest, has always been one of chosen few, while the many deserving players are often consigned to oblivion. In Pakistan, the structural inadequacies of first-class cricket, without a sturdy financial framework or a well-established system, meant that only a handful of exceptional players were handpicked. The absence of substantial cricketing infrastructure was significantly conspicuous in regions beyond Punjab and Sind. These two provinces, predominantly Lahore and Karachi produced the bulk of Pakistan’s cricketers, while other regions such as the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) and Balochistan, loitered unattended, dawdling on the sidelines. In the early 1970s, it was A.H. Kardar’s initiative in promoting departmental teams that truly allowed Pakistan cricket to thrive. This was essential, quintessential for so many players who, without institutional backing, may never have had the chance to rise through the pathways. Departmental cricket in Pakistan became a breeding ground for a generation of cricketers who would go on to become celebrities, the legends.

Even as Pakistan dominated the world stage in sports like hockey and squash, cricket held its own, evolving as a central and progressive force in the nation’s psyche. The likes of Majid Khan, Zaheer Abbas, Javed Miandad, and Imran Khan, personalities whose expertise rivetted audiences around the world fashioned the core of Pakistan’s cricketing identity. They were the country’s response to the progressive world, an answer to the inadequacies of Pakistan’s cricketing framework.

Yet, even among this glistening constellation of the personalities, the showstoppers, there were those who preferred not to ply their skills in county cricket, remaining loyal to their regional and departmental teams. Wasim Bari, Abdul Qadir, Iqbal Qasim, and Wasim Raja, despite their immense talent, chose to stay rooted in Pakistan’s domestic setup, a testament to their commitment to the country’s cricketing infrastructure. They played for national institutions such as Pakistan International Airlines, Habib Bank, and the National Bank, contributing not just to their teams but also to the nation’s sporting narrative.

From the 1950s to the 2020s, Pakistan’s cricketing history is replete with players who became prominent and sources of phenomenal success in their time: Hanif Mohammad, Fazal Mahmood, Majid Khan, Imran Khan, Javed Miandad, Wasim Akram, Saeed Anwar, Inzamam-ul-Haq, Waqar Younis, Saqlain Mushtaq, Younus Khan and now Babar Azam, to name a few. The story of their rise, however, is not just one of natural talent. It is the story of cricket as a great leveller, a sport that marginalizes the social and economic divides, elevating those from the humblest backgrounds into the limelight, to international acclaim. But it is not without its dark undercurrents. The story of those whose immense potential was undone by personal failings, Mohammad Asif, Mohammad Amir, Kamran and Umar Akmal is one of the cricket’s tragic ironies. Their careers stand as cautionary tales, reminders of how greatness can be squandered when self-discipline falters.

The duality of Pakistan’s cricketing heroes is best exemplified by the contrasting trajectories of Imran Khan and Javed Miandad. Imran, the Oxford-educated, aristocratic product of a well-heeled Jalandhar family, brought a cosmopolitan air to Pakistan cricket. He hailed from a lineage steeped in privilege, a family with ties to the highest echelons of both sporting and political life. His cousins Majid Khan and Javed Burki, themselves captains of Pakistan, were part of a cricketing dynasty that boasted three generations of Test cricketers. Javed Miandad, on the other hand, came from far humbler beginnings. His rise through the ranks, from his early triumphs in the Under-19s to his meteoric debut in first-class cricket, was fuelled by a raw, instinctive genius. While Imran represented the cultured, cerebral side of cricket, Miandad was the quintessence, incarnation of street-smart, aggressive cricket, driven by grit, passion, and an indomitable will to succeed.

This dichotomy between the aristocrat and the commoner, between privilege and perseverance, mirrors the broader dynamics at play within Pakistan cricket. Cricket has always been an amalgam of contrasting forces, of order and chaos, of discipline and flair, of the planned and the spontaneous. It is in this interplay that the true magnificence of cricket lies, for it reflects not just the intricacies of a sport but the very essence of the human condition.

And yet, despite the lack of formal infrastructure, Pakistan has consistently produced cricketers of outstanding calibre. It is a mystery of sorts, an improbable triumph in a nation where pathways to sporting success are often murky and ill-defined. Perhaps it is this very unpredictability, the paradox of brilliance emergent from chaos that makes Pakistan cricket so captivating. Here, the extraordinary is born from the ordinary, and the sport outdoes mere competition to become a metaphor for life itself.

Wasim Akram's ascent in cricket is akin to an unfolding myth, where the improbable converges with the inevitable. Born in Lahore and a product of Ludhiana Gymkhana, Akram was but a humble left-arm fast bowler, often overlooked in the context of his college team at M.A.O College, where he was hardly deemed meriting a place in the playing XI. The oversight of his abilities, attributed to youth and inexperience, was a reminder that genius often eludes the untrained eye. How little did they know that this raw, unrefined fast bowler would soon seize the world’s imagination through a rise so meteoric it bordered on the fantastical.

It was at the Khan Mohammad Talent Hunt camp that providence began to unravel Akram’s hidden legerdemain. He was short-listed to travel to Karachi to attend to phase two of the camp. There, in the bustling cricketing metropolis of Karachi, his talent could no longer remain obscured. Javed Miandad, a maestro of his own time, recognised in Akram something that eluded others: the ability to redefine left arm fast bowling. It was Miandad who ushered the young bowler in Pakistan’s national team, compelling selectors to name him in a team versus New Zealand at Rawalpindi. What followed was not just history but a moment of providence as Akram debuted in first-class cricket and picked a haul of seven wickets in an innings, set to forever alter the course of cricket.

Miandad himself symbolized the soul of Pakistan cricket, a representation whose brilliance lay not only in his technical mastery but in the essence of his being resilient, rebellious, and unabashedly strategic. From his earliest days in Karachi, where he would travel on the back of Aftab Baloch’s motorcycle to practice, Miandad’s journey was one discernable by a steadfast determination to assert his place in cricket history. His debut for Pakistan, punctuated by a triple century in first-class cricket, and his consistency across decades, ensured his batting average never plunged below the hallowed 50.00 in Tests.

These moments, these achievements, are not only the statistical milestones. They are, rather, glimpses into the philosophy of cricket as it is lived and breathed by these celebrated players from Pakistan. Akram’s success at Dunedin, where he dismantled the New Zealand team with ten wickets in his second Test, is not just an example of fast bowling at its finest, it is an epithet of cricket’s changeable, transformative character. It validates how a player's talent can surface fully formed in international competition, resisting every expectation.

In a parallel, Miandad's ability to shepherd Pakistan through tumultuous moments whether standing firm in adversity or taking to pieces the world’s best bowlers with a peculiar genius is a witness to the translucent spirit that underpins greatness. His street-smart cricketing intellect, honed in the alleys and grounds of Karachi, was more than a technical asset; it was a reflection of his consciousness, one that constantly challenged the status quo and strived to defy impossibilities imposed by the circumstance. He was there to confront and fight, unforgivingly contrary to his polite demeanour as a simple, caring man.

Imran, Akram, and Miandad represent a triumvirate of excellence in Pakistan’s cricketing narrative, each contributing not just skill, but a philosophy of life lived through cricket. Imran, with his aristocratic bearing and Oxford education, played the game as a leader of men, inspiring his team through discipline and an almost regal sense of purpose. Miandad, in contrast, was the tactical genius, the man who could see a hundred ways to win where others saw none, his mind always calculating, always scheming. And Akram, with his natural flair and charisma, was the epithet of cricket’s raw beauty, the perfect confluence of art and sport.

In his early days of Javed Miandad’s cricketing parlance was one of a teenager high on self-belief and conviction. He believed in masterminding play and based his success on perfect execution. One can trace the genesis of his brilliance not only to natural talent but also to the deeply braided mentorship he received. It was often that the late Aftab Baloch, a cricketer of repute himself, would fetch Javed on his motorcycle, traversing the bustling streets of Karachi to the nets. These rides, like the understated beginnings of many great stories, confined in their simplicity the starts of something extraordinary. Baloch, a mentor and chaperon, saw in the adolescent Javed the potential to override cricket’s ordinary dimensions. And in those early days of drudgery, grind and practice, the conformations of an amazing career began to take shape.

Javed’s father, Miandad Noor Mohammad, a man of quiet resilience, served in the Police Department but his heart, much like his son’s, belonged to cricket. In the cricketing landscape of Karachi and in distant postings to Ahmedabad and Baroda, he nurtured the game, establishing a club where the Miandad name would resonate long before Javed ascended to world fame.

Cricket was, for the Miandad family, a vocation passed through generations. Javed’s brothers, Bashir, Anwar, and Sohail were all first-class cricketers, each contributing to the Miandad legacy. Anwar, stood on the precipice of Test debut, attending as the 12th man for Pakistan twice. While in later years, Javed’s nephew, Faisal Iqbal, would hoist his maiden Test century versus India at Karachi in 2005-06, a performance that seemed almost predestined.

It is in the outlay of such familial dedication that one begins to understand Javed’s rise. His performances were not just his own but part of a larger narrative, a lineage that wrapped cricket’s traditions while constantly seeking to push its precincts. Under the captaincy of Azhar Khan, a future Test player himself, Javed was selected for the Pakistan U-19s tour of England in 1974. It was there he announced himself to the world, and still a teenager, he scored a triple century in first-class cricket, an achievement that would serve as a prelude to his grander exploits in international cricket.

When Javed first played for Pakistan at Edgbaston in the Prudential World Cup in 1975, debuting against the compelling and equally robust West Indies, it manifest the beginning of a career that would reshape the very essence of Pakistan cricket. And when, in 1976, he strode onto the pitch at Lahore, facing New Zealand in his maiden Test, the 163 runs he amassed in the first innings were not just a statement of intent, it was a prelude to a career where his batting average, from his debut until his 124th match, would never once slump below the miraculous 50.00.

Miandad’s career, like those of the greats, excels numbers. His batting, at once pragmatic and inspired, was a reflection of the man himself, a thinker, always calculating, always prepared to seize the moment. Through his innings, Pakistan’s cricketing narrative discovered its most eloquent expression, as Javed's rise symbolized the perpetual truth that preeminence is not merely achieved but earned through countless moments of perseverance, mentorship, and uncompromising belief.

Wasim Akram’s mounting to the acmes of cricket reads like a tale plunked from the realms of myth. A raw, unpolished left-arm fast bowler from Ludhiana Gymkhana, who could scarcely get a place on the M.A.O College XI, seemed an unlikely prospect to attain distinction. Though a part of the college team, he was seldom called upon to play, for the captain and management believed they had better bowlers. To them, Wasim was too young, too unrefined, and far from readiness to be the part of competitive cricket. They, like many in the world of sport, were shackled by their own preconceived contemplations and philosophies, failing to catch sight of the potential that lay quiescent and unexpressed underneath the surface.

But within weeks, the world, including those early skeptics and doubters, would be left speechless, for Akram’s rise in international cricket was nothing short of a fairy tale, a story that defied conventional judgment. Akram’s self-discovery and mastery of the art began when he arrived at the Khan Mohammad Talent Hunt camp. Miandad invited him to bowl in the Pakistan nets, and in that brief period, an unassuming bowler from Ludhiana Gymkhana saw himself on the springboard, ready to catapult to world fame. Not only did Miandad handpick Akram for the President’s XI to face New Zealand in a three-day match at Rawalpindi, but he also wrestled to include him in the team against the wishes of Haseeb Ahsan, the then Chairman of Selectors. Haseeb, an ex-Test player harboured reservations about selecting someone untested in first-class cricket.

Miandad, in an aberrant but resolute stance, insisted that Akram be taken to Rawalpindi and, more importantly, be named in the playing eleven. What followed would become a fairytale arrival of Wasim Akram, presumably cricket history’s best ever left arm fast bowler. The world would soon witness the rise of a bowler whose skill, speed, and swing would leave batsmen bewildered for the next twenty years. In that moment, Akram’s story became intertwined with the narrative of Pakistan cricket itself, a tale of extraordinary talent meeting opportunity. The rest, as it is often said, is an epic, truly part of a folklore.

Despite a flabbergasting, overwhelming and an equally dumbfounding first-class debut where he picked seven wickets in an innings and a rather inconspicuous maiden One Day International against New Zealand at Faisalabad, Wasim Akram's career was steadfastly championed by Javed Miandad. The trust that Miandad placed in Akram would soon reverberate worldwide, though his first Test performance seemed modest. Yet, even then, there were flashes of brilliance, something special, his pace, his shoulder-driven action, the perfectly locked wrist, and his innate ability to swing the ball, all combined in one left the top batsmen in a state of stupor.

And it was at Dunedin, during only his second Test match, that Akram truly announced himself to the world. There, he wrecked the New Zealand batting lineup, picking ten wickets announcing his arrival in the grandest of fashions. The cricketing world had just witnessed the genesis of a rollicking superstar. His rise in limited-overs cricket was nothing short of a manifestation of supreme ability, otherworldly, unnatural. His first One-Day International in Australia, during the preliminary rounds of the Benson & Hedges Championship, saw him decimate the Australian top order at Melbourne, dismissing five batsmen, three bowled,one-hit-wicket and another caught by Tahir Naqqash, leaving the opposition in total disarray. It was a moment that invigorated his reputation as someone natural, his ability and performance based on dynamism and intensity, a bowler capable of transforming the course of a match with a single spell of brilliance. It was in this very match that Imran Khan, returning to international cricket, first beheld Akram's raw talent, and thus began the mentorship that would overshadow even Javed Miandad’s earlier influence.

In an almost diabolical twist, Akram openly referred to Imran as his role model, seldom acknowledging the pivotal role Javed had played in sighting him from absolute obscurity. The narrative, at its core, reflected the subtle politics of credit, a phenomenon often associated with Imran, whose self-centric tendencies were well known. Yet, over time, Akram did occasionally reaffirm the profound impact Javed had on the formative years of his career. This dynamic between mentors, one brimming with public adulation, the other somewhat eclipsed by the larger-than-life persona of Imran depicts ambition, influence, and the nuanced struggle for recognition in the apparitions of cricketing greatness. From that point on, Akram never looked back. His first-class debut against the touring New Zealand had been equally exceptional, with a seven-wicket haul that left them in tatters. And thus began his career, reflective of unremitting dominance.

The Three Captains

The captains under whom Akram blossomed and flaunted his trade, Imran Khan, Javed Miandad, and later Akram himself, each represented distinct eras of Pakistan cricket. Imran Khan, the disciplinarian, led with an authoritative presence and left an indelible impact. Miandad, tactically astute and arguably the shrewdest of the three, played with a strategic genius. Akram, during his second tenure as captain, came into his own, refining his captaincy as he mastered the métiers, the callings.

The narratives of these three greats, Imran, Javed, and Wasim are best represented through a series of powerful vignettes, moments that abridge not just their cricketing expertise but the character of Pakistan cricket itself. These portrayals reveal the tension and triumphs, the prettiness and the battles, within a sport that often mirrored the social and political complexities of the nation.

Miandad, in particular, stands as an illustration of insightful symbolism. He personified the street-fighter, the patriarch of Pakistan cricket, his career a reflection of both the triumphs and the unspoken disappointments. The rebellion against him during the 1981-82 series and his subsequent survival, based solely on his indispensable role as a player, speaks to his resilience. He served Pakistan cricket with a clemency and dignity that was intertwined with a deep sense of pride and nationalism. His career, however, was not without its afflictions, a layered experience of success and despondency, pride and pain.

The careers of Imran Khan, Javed Miandad, and Wasim Akram are case studies in the pressures that superstars withstand, the strain of constantly surviving under the burden of expectation, and how each learnt to thrive within the unique requirements of the cricketing world. Watching these players play was nothing short of exhilarating. On countless afternoons, Miandad stood alone, in adversity, resisting the greatest bowlers in the world and spurring his team to an improbable win.

Similarly, Imran Khan’s presence was magnetic. Tall, handsome, and with a princely deportment, he was often unplayable. His successes only seemed to increase his aura, and the sight of women screaming at Lahore’s Gaddafi Stadium, more mesmerized by his allure, the uninterrupted appeal than his cricket, was a verification of the legend he had become, both as player and as a man admired for his handsomeness. And then, there was Wasim Akram. His skills, unmatched and unforgettable, were on full display during the Rawalpindi Test against Australia in 1994, where even the indomitable Steve Waugh was rattled by Akram’s downright brilliance. That performance, like many others, signified the spirit of Pakistan cricket, savage, competitive, and capable of moments of absolute magic. Akram’s legacy, like that of Imran and Miandad, is everlasting, an persevering symbol of the elevations that cricket, and its players, could achieve.

His achievements stand unchallenged, vivid memories to the synthesis of natural flamboyance, flair, and captaincy discernible by a unique vernacular. As captain, he filled cricket with colloquial creole and the rhythmic patterns of Punjabi dialect, hewing a convivial atmosphere teeming with wit and energy. His performances, radiant and often bordering on the inspirational, seemed to reflect his very being, an extension of his personality. In stylistic contrast to his more conventional and reserved teammates, his displays were stirred with an irrepressible spirit, a dynamic strains between exuberance and control.

From the vantage points of dressing rooms, commentary boxes, and within the receptacle of Pakistan cricket, one could see this essence trickling down through every tier. This was a generation that wrapped aggression with flummoxing ease, a spirit of imperial grandeur intertwined with an illimitable capacity for daring. They belonged to a time when cricket wasn’t merely a sport, it was a declaration of intent, a manifestation of audacity. Barring Miandad, the other two, not through what transpired around them helped Pakistan cricket in anyway. Akram’s flirtations with controversies, the match-fixing allegations and shifting to a career in media instead of playing a central role in the game’s development, and Imran’s decisions while he was the Prime Minister, seemingly preconceived reducing the country’s first-class cricket to six teams, a frail attempt to replicate model in place in the Sheffield Shield in Australia, a country of 26.46 million as compared to Pakistan’s 280 million seemed absurd. It hurt Pakistan’s cricketing infrastructure. And how, even after he had retired attempted to have Javed Miandad removed as captain to bring in Wasim Akram in 1992-93 also scarred the future of country’s cricket, where player power and individual began to take roots within the team. It followed the turbulent 1990s when Pakistan produced outstanding talent, the finest cricketers still one controversy after another left the team in absolute shambles.

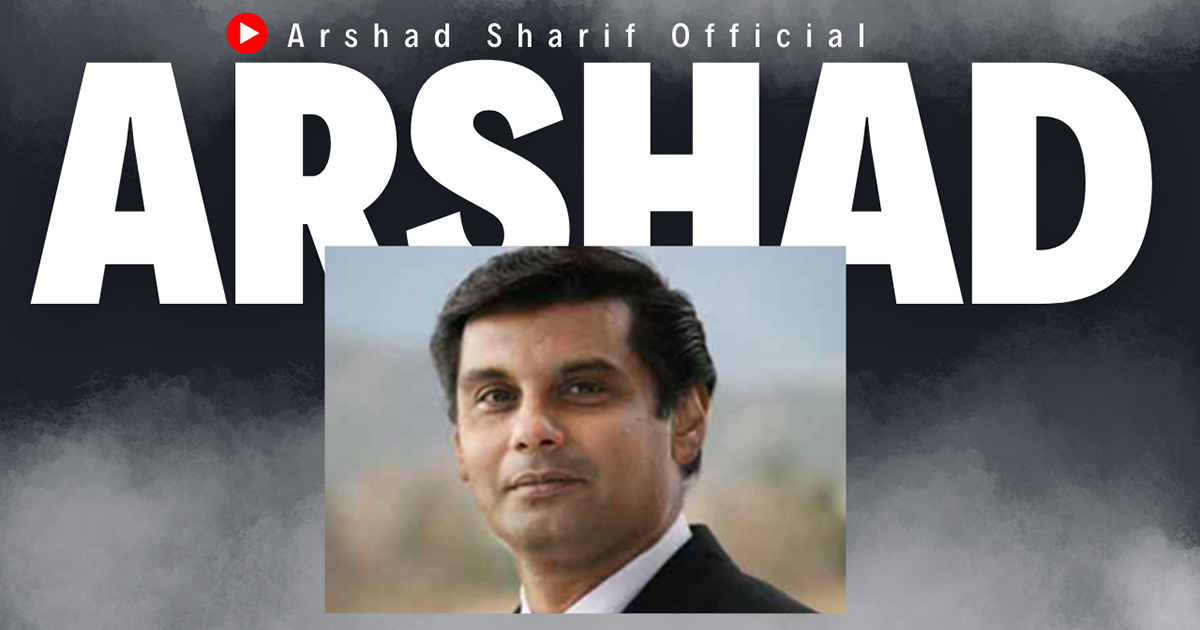

Dr. Nauman Niaz is the Sports Editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting and Journalism and a regular cricket correspondent, covering 54 tours and three ICC World Cups. He has written over 3500 articles, authored 14 books, and is the official historian of Pakistan cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes – 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has received the highest ratings and acclaim.

KEY POINTS:

- Dr. Nauman Niaz begins a two-part series on Pakistan's Test cricket issues.

- Pakistan's cricket struggles with leadership and performance integrity.

- Shan Masood's century contrasts with the team's overall defeats in recent matches.